How to Really Interpret DNA Ethnicity Tests

Do “ethnicity” DNA tests really work? How accurate are they? Which company should you test with? I’ll try to demystify these commercial DNA tests, without getting too technical, and hopefully shed some light on what you should, and shouldn’t, expect.

DNA “Ethnicity” Tests

We’ve all seen the AncestryDNA commercials: from the lederhosen-wearing man named Kyle who discovers he’s 52% Irish/Welsh/Scottish and 0% German, to the stubborn Scottish grandfather who turns out to be quite Italian.

Do these “ethnicity” DNA tests really work? How accurate are they? Which company should you test with? I’ll try to demystify these commercial DNA tests, without getting too technical, and hopefully shed some light on what you should, and shouldn’t, expect.

If you truly want to know “where you come from” and who your ancestors were, traditional document-based genealogy is still your best bet. That said, DNA testing can augment that research and sometimes help break through “brick walls” by finding relatives, or “DNA matches”. DNA testing is especially helpful for those who can’t access a genealogical paper trail, such as adoptees. DNA matches to cousins are the most helpful aspect that a DNA ancestry test can offer.

The 5 most popular companies to test with are AncestryDNA, 23andMe, FamilyTreeDNA (all three based in the U.S.), MyHeritage (based in Israel), and Living DNA, associated with FindMyPast (based in the UK). Knowing where these companies are based, and who their target market is, is crucial to choosing the right test. More on that later… All of these companies will provide you with ethnicity/ancestry estimates overlaid on a map and a list of people who share DNA with you.

The “ethnicity” DNA test that I’m referring to is called an autosomal DNA test, an admixture analysis, or more accurately a biogeographical ancestry analysis. According to the International Society of Genetic Genealogy, an admixture analysis “is a method of inferring someone's geographical origins based on an analysis of their genetic ancestry. An admixture analysis is one of the components of an autosomal DNA test.” The results are called different things by the different companies: “ethnicity estimate”, “ancestry composition”, “family ancestry”, and so on. There are other types of DNA tests available for consumers, but we’ll save that for another article.

How accurate are these tests when compared to traditional, paper-based genealogy?

Here’s a look at my ethnicity results from the 5 different companies compared to the genealogy I’ve researched.

Seeing results like this can be confusing, and may make you want to dismiss the results altogether as fake science. However, to understand how companies get their test results, and why your ethnicity estimates might vary drastically from one company to another, we need to explore the concept of reference populations. Reference populations are a group of modern individuals whose DNA can be used to represent a place or region. Each testing company’s reference population is different, based on their target market. If a company doesn’t have a reference population that reflects your ancestry, your results won’t show you where your DNA is from. Living DNA, for example, focuses on a clientele that has British roots. So, if you’re trying to determine where in England your ancestors came from, their DNA test is a good option. If you have Jewish roots, Israeli-based MyHeritage is currently the only company that tests against these 6 Jewish reference populations: Ethiopian, Sephardic, Mizrahi, Ashkenazi, European and Yemenite.

The Science Behind “Clusters”

Companies put their reference population testers into different clusters based on haplotypes (a set of DNA variations that tend to be inherited together) and population-specific alleles (a variant form of a given gene). They assign names to these clusters based on geographical region. Some companies use specific current-day political boundaries (like “German”) and some will offer up a more generic term like “Germanic Europe”. Though it might be more satisfying to a tester to receive a very specific result, know that for some countries, this can be problematic. Centrally-located Germany, for example, has shared DNA with neighbouring regions over a long period. In contrast, isolated communities like the Karitiana people of Brazil (an indigenous group that lives in the Western Amazon) have alleles that are completely unique to them. When a reference population has many private alleles, they are considered genetically distinct. Therefore, when a tester’s DNA includes these private alleles, it’s easy to trace them back to a particular place or “ethnicity”. It is much harder to identify DNA from Germany, as Germany is a relatively new country, and “Germanic” people never came from a particular place.

Per Ancestry, “The reference panel is made up of people with a long family history in one place or as part of one group. To make it into the AncestryDNA reference panel, people need two things: a paper trail that proves their family history, and DNA confirmation of their ethnicity. It's not easy to make it into the panel! To estimate your ethnicity, we compare your DNA to the people in the reference panel and look for DNA you share. If some of your DNA is similar to the DNA of people from Senegal, for example, we assign that part of your DNA to our Senegal region.”

Understanding how each company names their clusters is also important. If your ancestors were from Fiji, for example, you might be surprised to learn that that country won’t appear in any DNA test that’s on the market today. That’s because none of the companies have a cluster called Fiji. Chances are, your test will indicate “Polynesian” ethnicity or simply “Oceania”. Click here to view a current list of all “ethnicity” clusters these companies test against. Over time, your estimates will likely get better as algorithms are improved, more reference populations are added, and more clusters appear. Don’t get attached to your ethnicity estimates—expect changes over time. Another important thing to remember is that you may not have inherited any DNA from a particular ancestor. Even if you are certain that your 6th great-grandmother was Mexican, for example, your DNA may not show this if you did not inherit her DNA generations later. More on this below.

For an in-depth comparison of available DNA tests, click here to see a chart from ISOGG (the International Society of Genetic Genealogy).

“How Far Back” Do the Tests Go?

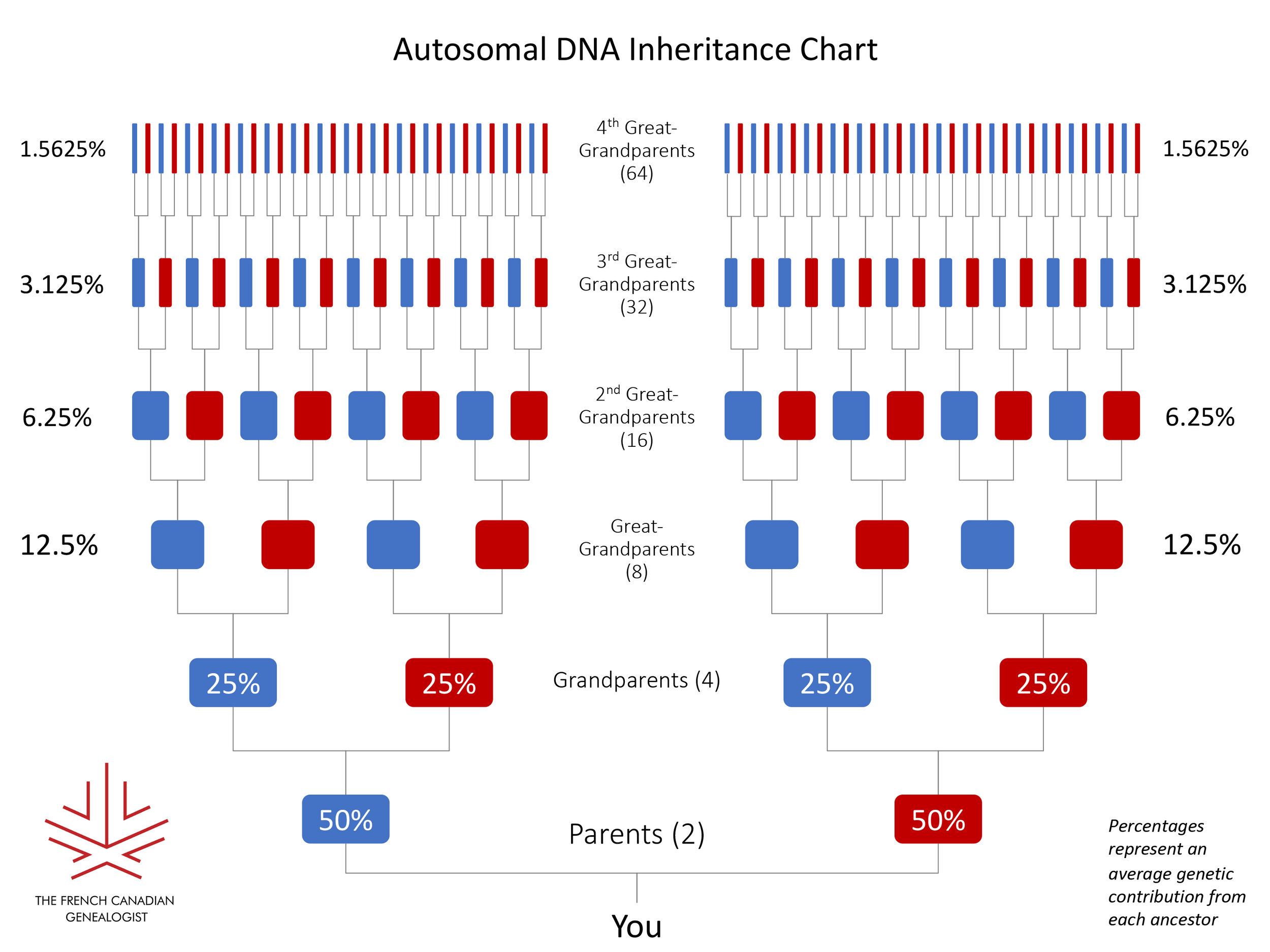

It’s also important to understand that most of these ethnicity estimates only go back about 200 years, or about 5 or 6 generations. That’s because the probability of inheriting DNA from an ancestor decreases with each generation. You may not inherit any DNA at all from a particular ancestor (like your Mexican 6th great-grandmother I mentioned earlier), especially the further back you go in your family tree. Here’s a chart to illustrate.

So while your genealogical and documented family tree might go back 14 generations with thousands of ancestors, your genetic family tree has only a fraction of those thousands of persons—only those whose DNA you’ve actually inherited.

Some companies will include probability ranges with their estimates, which tells you how confident they are about the result they’re presenting. Chances are that regions that don’t match up with your genealogical family tree will have a 0% to xx% range, as these AncestryDNA results showed for my non-existent British and Swedish roots.

Testing companies continuously improve their algorithms and add samples to their reference populations. This means that your results will probably change over time. Hopefully this means those outliers that have you scratching your head will probably disappear. In the meantime, any estimates ranging from 0-10% should be considered less reliable.

A New, Gigantic Family

One aspect of taking a DNA test that can be overwhelming is the sheer number of DNA matches, or cousins, you’ll likely discover. You can be confident that anyone who shows up on your DNA match list truly does share DNA with you, meaning that you have a common ancestor somewhere in your family tree. What may not be accurate is the relationship shown, which is why some companies will have a “predicted relationship” of “3rd to 4th cousin”, for example. If any strange results show up (like that time when one of my aunts was reported as my half-sister), there are normally resources on the company’s website that explain how they predict relationships, and how mistakes can happen.

Some astounding facts:

All Europeans living today are related to the same set of ancestors who lived 1,000 years ago. Put another way, anyone alive 1,000 years ago who left any descendants will be an ancestor of every European. This is why most people with European roots are related to Charlemagne.

Everyone in the world shares a common ancestor in the last 2,000 to 4,000 years. We’re all hundredth cousins or so.

A Word of Caution

If you’re debating on whether or not to take a test, you also need to be ready for the possibility of discovering close relatives you didn’t know you had, or finding out that people you thought were family aren’t related to you at all. These results can open a Pandora’s box that can create a range of emotions. For some this may result in unexpected stress or even possible psychological issues. While finding a half-sibling might be exciting for some, it may come as a shock to other family members, who may not welcome the news.

What about Privacy Concerns?

Whether or not to take a DNA test in light of privacy concerns is a personal decision—one that should be made based on the testing company’s privacy policy, applicable laws where you live, and your own level of comfort. Here are some resources to help you make an informed decision:

The International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki’s page on Privacy policies, consent forms and terms and conditions;

Sunny Jane Morton, “Do DNA Tests Put Your Personal Information at Risk?”, FamilyTree Magazine;

Amy Johnson Crow, “The Ethics of Genetic Genealogy: Tips from Judy Russell”, 7 Feb 2019 (available as a video or podcast).

Sources and further reading:

AncestryDNA, “AncestryDNA® Reference Panel” (https://support.ancestry.com/s/article/AncestryDNA-Reference-Panel).

The International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki’s page on Privacy policies, consent forms and terms and conditions. https://isogg.org/wiki/Privacy_policies,_consent_forms_and_terms_and_conditions

Amy Johnson Crow, “The Ethics of Genetic Genealogy: Tips from Judy Russell, 7 Feb 2019, https://www.amyjohnsoncrow.com/ethics-genetic-genealogy/ (available as a video or podcast interview).

Debbie Kennett, “Ethnicity Percentages Demystified”, presentation at Family Tree Live, Alexandra Palace, London, 27 Apr 2019, You Tube (https://youtu.be/BUF0Stujq6M).

Sunny Jane Morton, “Do DNA Tests Put Your Personal Information at Risk?”, FamilyTee Magazine (https://www.familytreemagazine.com/premium/do-dna-tests-put-your-personal-information-at-risk/).

Peter Ralph and Graham Coop, “The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe”, PLOS (https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555).

Douglas L.T. Rhode and Steve Olson, “'Most recent common ancestor' of all living humans surprisingly recent”, 2004, Yale University press release (http://www.stat.yale.edu/~jtc5/papers/CommonAncestors/NatureAncestorsPressRelease.html).

Moss Stern, “MyHeritage vs 23andMe vs AncestryDNA - Battle of the Titans 2020”, DNA Weekly (https://www.dnaweekly.com/blog/myheritage-vs-andme-vs-ancestrydna/).