Executioner

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Le Bourreau | The Executioner

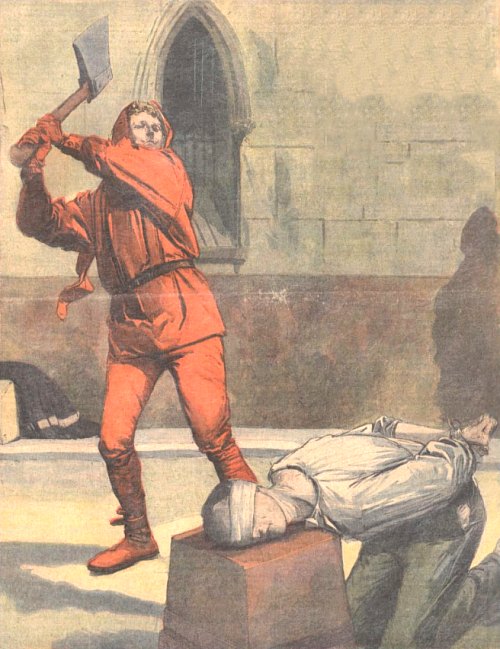

Medieval executioner, artist unknown, La France pittoresque, www.france-pittoresque.com.

The bourreau, or executioner, was the only man who had the right to kill and carry out death sentences ordered by the court. The state furnished the executioner's tools: a bar to break limbs, an iron to brand the fleur-de-lis, a rope to hang the culprit, etc. In New France, many crimes could lead to a death sentence: murder, duelling, the fabrication of counterfeit money, robbery committed at night, burglary, arson, the concealment of a pregnancy, infanticide, rape, indecent assault, desertion, treason, homosexuality and bestiality. However, in the colony, it was mostly the thieves, concealers, murderers, and counterfeiters whom the judges punished with death. In New France, a little over 80 persons were executed between 1663 and 1760.

Executions were done publicly in order to make examples of the guilty, instil fear in the public and dissuade them from committing similar crimes. They often attracted sizeable crowds who came to listen to the reading of the judgement and to watch the guilty suffer the ultimate punishment. Capital punishment was usually done by hanging. In the case of guilty nobles, they were to be decapitated. In reality, however, very few nobles in New France were convicted of crimes. The few that were were found guilty of duelling and killing their adversary. In all cases, however, they were able to flee before even being arrested. Aside from hanging and decapitation, the two other methods of capital punishment were by burning and execution by the wheel.

The executioner was not only responsible for carrying out death sentences. He was also responsible for handing out corporal and other punishments ordered by the court, such as whipping, branding (marking with a hot iron), sending one to the galleys, banishment and putting someone in le carcan (a restraining device used as a form of corporal punishment). In the colony, these types of corporal punishment and public humiliation were far more common than imprisonment.

Execution of a man found guilty of poisoning several people ("Antoine François Derues rompu vif et jetté au feu le 6 mai 1777 pour avoir empoisonné plusieurs personnes", engraving from unknown artist, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr).

The executioner was often a man previously sentenced to death pardoned in exchange for his services. He was on average 30 years of age, and said to have trouble keeping an ordinary job. The occupation of executioner certainly wasn’t desirable, and most men who took on this occupation didn’t do so by choice. The executioner was at the very bottom of the social ladder, his job the most shameful of all. He and his family were looked down upon and often ridiculed in public. His residence was always away from the town centre—he and his family ostracized from society. For his work, the executioner was paid 300 livres annually. In the 18th century, he received an additional 10 francs for each capital execution and his lodging was paid for by the king.

The official executioners in the Laurentian valley were as follows:

Jacques Daigre (1665-1680)

Jacques Rattier (1680-1703)

Jacques Élie (1705-1710)

Pierre Rattier (1710-1723)

Gilles Lenoir dit Le Comte (1728-1730)

Guillaume Langlais (1730-1733)

Mathieu Léveillé (1733-1743)

Jean-Baptiste Duclos dit Saint-Front (1743-1750)

Jean Corolaire (1751-1752)

Pierre Gouet dit Lalime (1754-1755)

Denis Quavillon (1755)

Joseph Montelle (1755-1759)

The last person to be publicly executed in Québec City was John Meehan on March 22, 1864. He had been found guilty of murder after a bar fight went too far and his opponent died of his injuries. Newspapers reported that a crowd of 5,000 to 8,000 people witnessed his execution.

Article appearing in the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent on 16 Apr 1864, page 7.

Photo of John Meehan, likely taken near his execution date (Morrin Centre, Québec).

Many accounts claim the last public hanging in Canada took place in Ottawa on February 11, 1869. On that date, Patrick J Whelan was executed for the political assassination of Thomas D’arcy McGee. But was he truly guilty? Listen to this podcast to find out.

Photo of Thomas D’Arcy McGree (Wikimedia Commons)

Photo of Patrick James Whelan (Library and Archives Canada)

Sources:

André Lachance, Délinquants, juges et bourreaux en Nouvelle-France (Montréal, Québec: Les Éditions Libre Expression, 2011), 237 pages.

Jeanne Pomerleau, Arts et métiers de nos ancêtres : 1650-1950 (Montréal, Québec: Guérin, 1994), 45-56.