Faux-Sauniers in New France

In the 18th century, over 600 convicted French criminals were exiled to Canada to boost the population and help develop the land. Some deserted and some continued a life of crime, but most settled into farming life and started families. This is the story of the faux-sauniers.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Off to Canada for the rest of your life!

The story of the “faux-sauniers” exiled to New France

The “saunier” or “paludier” was a worker who extracted salt from seawater in a salt marsh. Under France’s Ancien Régime, the saunier was more likely to be a salt merchant or vendor. The “faux-saunier” was a salt smuggler or trafficker, a real merchant running contraband.

Salt marshes of Île de Ré, 1907 postcard (Geneanet)

Aerial view of the salt marshes of Carnac, postcard (Geneanet)

The Gabelle

To understand why salt trafficking emerged, we must understand one of France’s most unpopular taxes, the gabelle. From the Middle Ages until the French Revolution, salt was sold at market prices, upon which was added the king’s duties, or gabelle. The revenues derived from this salt tax represented the largest portion of the king’s revenues.

Title page of the "Compilation of the ordinance … on the Gabelle, with edicts, declarations, letters patent, rulings and regulations (…),” Louis XIV, King of France (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

First page of the “Declaration of the King regarding salt and tobacco traffickers,” given at Versailles on February 15, 1744 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

At the end of the 17th century, King Louis XIV appointed Jean-Baptiste Colbert as Controller-General of Finances, among various other roles. Colbert aimed to bolster France’s economy by increasing tariffs and supporting public works projects. In 1680, he issued an ordinance that regulated the gabelle by zone and implemented harsh penalties for contraband.

"Carte des gabelles" (Map of the gabelle regions) (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Six regions were designated:

les pays de grande gabelle

les pays de petite gabelle

les pays de quart-bouillon

les pays de salines

les pays rédimés

les pays de franc-salé or exempts

Previous to 1680, salt was taxed at a uniform rate. As of Colbert’s ordinance, taxes were levied per region, and varied greatly. In the pays de la grande gabelle, salt was heavily taxed. Residents were obligated to buy a minimum quantity of salt annually for personal consumption, plus whatever they needed to cure their food or tan animal skins. The price of salt varied from 54 to 61 livres per minot. [A minot was a measure once used for dry matter, which contained half a mine. A mine corresponded to approximately 79 litres.] Two thirds of all salt revenues came from this region.

In the pays de la petite gabelle, restrictions were limited to having to buy salt from royal granaries. In these regions, the price of salt varied from 15 to 57 livres per minot. In the pays de quart-bouillon, the tax rate was lower since one quarter of their salt profits was automatically sent to the king. Here, the price of salt was 13 livres per minot.

"Le grenier à sel" (the salt granary), painting, 18th century (Musée national des douanes)

In the pays de salines, no gabelle was charged. Here, the price of salt was market-driven and fluctuated between 1 and 8 livres per minot. The pays rédimés were also exempt; salt prices here varied from 6 to 9 livres per minot. Nobles, the bourgeois and clergy were exempt from the gabelle altogether.

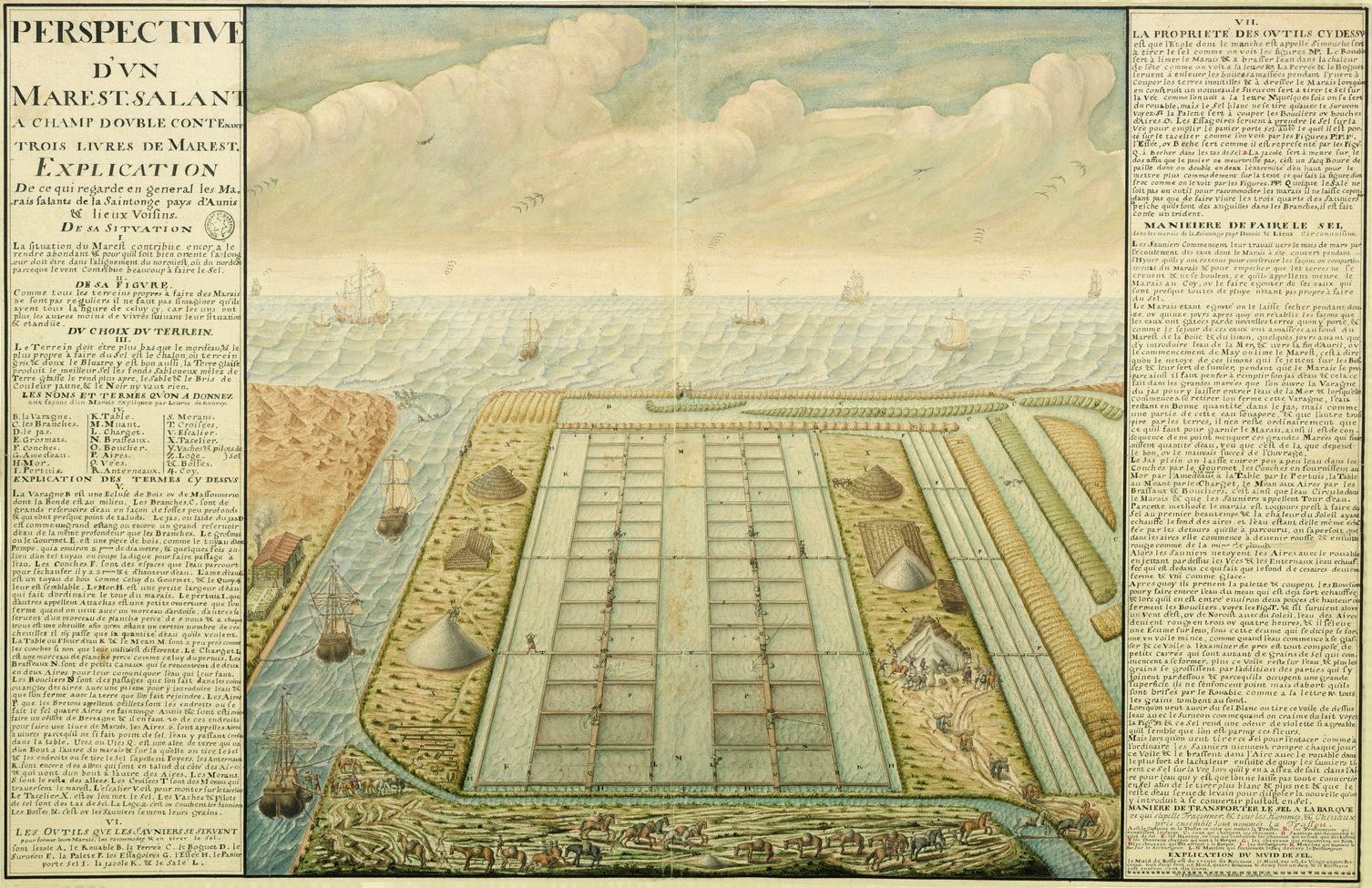

“Perspective of a double-field salt marsh," 18th century painting (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

"Les Paludières" (the salt workers), painting by Eugène-Jacques Feyen, circa 1872 (Musée des Marais salants, Batz-sur-Mer, Wikimedia Commons)

The Emergence of Salt Trafficking

"La Fouille en douane" (Customs Search), painting by Rémy Cogghe, circa 1890 (Musée d'art et d'industrie de Roubaix)

The 18th century witnessed a surge in living costs, leading to increased poverty in France. This economic hardship gave rise to the illegal salt trade known as “faux-saunage,” particularly in border areas. Here, contraband was a lucrative activity that could substantially increase family revenues. Smugglers purchased salt in low-tax regions and sold it illegally in high-tax regions. This illicit trade was not limited to men; women were also actively involved, often concealing salt under their dresses.

Faux-sauniers faced severe penalties if caught. An apprehended smuggler was usually sent to an overcrowded prison, where they spent anywhere between 10 days to 3 months, before eventually appearing before a judge. Sentences varied based on whether the crime was individual or committed within a group. Individual offenders, often carrying salt on foot, received relatively lenient punishments, while groups of traffickers using horses or carts faced more severe consequences. These smugglers were harder to catch, and judges made examples out of them with harsher penalties. A first offence resulted in a 300-livre fine, while recidivism could lead to the galley or even the death penalty. Alternatively, “la peine du Canada” could be handed down—exile to Canada.

A Canadian Punishment

At the height of faux-saunage, the Minister of the Navy and Colonies was trying to develop the economies of France’s overseas colonies. Jean Frédéric Phélypeaux, the Comte de Maurepas, was searching for a cost-effective way to send colonists to New France, to develop its agriculture and diversify the economy. France had enormous debts and Maurepas wanted to ease this burden through the revenue of its colonies.

Presumed portrait of Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Count of Maurepas, painting by Louis-Michel van Loo (Wikimedia Commons)

Maurepas found a solution in the justice system and, starting in 1720, he implemented a discreet method of forced immigration to New France. At its early stages, all sorts of prisoners were exiled, without regard to their suitability in the colony. Many of these men continued their illegal activities, causing the colonial authorities to vehemently oppose this immigration scheme. A decade later in 1730, Maurepas turned his attention to faux-sauniers. In French public opinion, men and women convicted of this offence weren’t considered hardened criminals, but victims of a draconian law aimed at curbing salt trafficking.

Since there was no gabelle in New France, convicted faux-sauniers would not be able to continue their illegal activity there. Contrary to the first batch of prisoners sent to Canada, the authorities and general population welcomed the faux-sauniers, who were seen as important contributors to the colony’s manual labour. The one exception was the clergy, who feared that the faux-sauniers’ lack of a moral compass would negatively influence Canadians.

Who Were the Faux-Sauniers?

Most of the faux-sauniers deported to Canada were from the north of the country, where trafficking was most prominent (the pays de grande gabelle). Many also came from areas located near port cities like La Rochelle or Rochefort, because it was cheaper to transport them to the ships making the ocean crossing.

Physical characteristics also determined who was sent to Canada. Maurepas wanted men who were in good physical shape to contribute to the development of the colony. This excluded men with disabilities or with contagious diseases, or those that were too old. In addition to gruelling physical work, these men also had to be able to deal with the harshness of winter. The average age of the faux-saunier in New France was 28.

In the early days of the immigration scheme, the authorities saw many desertions from married men. Deserters who were caught faced 3 months’ prison time; those found guilty of helping them escape faced a hefty fine of 500 livres. Eventually, only single men were chosen, as they were less likely to want to return to France. Those who were already married could request that their wives and children be brought to Canada.

“(... ) It having come to our attention that several of the said prisoners and faux-sauniers are planning to escape by sea or by land, we, in consequence of His Majesty’s orders, forbid all persons brought to this country to leave on any pretext whatsoever, on penalty of three months’ imprisonment for the first offence and corporal punishment in the event of a repeat offence, let us similarly inhibit and forbid the captains and masters of ships from receiving on board any of the said prisoners and faux-sauniers, wherever they may appear in this colony to embark, and all persons (...) from aiding and abetting any of the said faux-sauniers and fugitive prisoners in their escape, under penalty of a fine of five hundred pounds (…).”

Extract of an 1736 ordinance by Intendant Gilles Hocquart

Maurepas sought out day labourers and ploughmen, not skilled workers—unless they were carpenters, blacksmiths, coopers or charcoal burners. Weavers and merchants were considered unnecessary and of little value to the colony. A man named Gilles Le Noir was chosen because of his role as an executioner, which New France needed at the time. If the faux-saunier had a previous occupation, he was likely to continue this work in New France. Otherwise, he became a ploughman, day labourer, domestic servant or voyageur.

Upon their arrival in Canada, most faux-sauniers were given a choice: join the military or work as a contracted labourer for a Canadian habitant. The vast majority chose to work the land for an engagement period of three years. The conditions around these work contracts were strict: the employee had no freedom of movement, wasn’t allowed to go to an establishment selling alcohol, couldn’t get married, or leave his employment for whatever reason.

"At the Plough", 1884 painting by Vincent Van Gogh

The Last of the Faux-Sauniers

The forced immigration schedule lasted until 1749, when Maurepas was disgraced by Louis XV and removed from his role. Researchers have identified a total of 607 faux-sauniers sent to Canada between 1730 and 1749. This number is approximate, however, as it only captures men who came aboard royal ships, not those that may have come aboard merchant ships. Remarkably, half of all French migrants who came to Canada during this entire period were faux-sauniers.

Of the 607 faux-sauniers sent to New France, 362 remained at least for a time. The remainder died at sea, deserted or were repatriated to France due to illness. 241 faux-sauniers settled permanently. Those who signed engagement contracts with Canadians were most likely to stay, as they normally lived and worked with them and their families. Eventually, they forged their own ties within the community, married and had families of their own.

The story of the faux-sauniers provides a unique glimpse into the social and economic challenges of 18th-century France and their unexpected role in shaping the history of New France.

Click here to view a list of faux-sauniers on Wikitree (still under development).

Click here to view a list of faux-sauniers on Fichier Origine.

Discover the stories of faux sauniers Pierre Philippon dit Picard and François Prud’homme dit Failly.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Merci!

Sources and additional reading:

Philippe Fournier, La Nouvelle-France au fil des édits (Septentrion, Québec : 2011), p. 478, 504.

Josianne Paul, Exilés au nom du roi : les fils de famille et les faux-sauniers en Nouvelle-France, 1723-1749 (Sillery [Québec], Septentrion, 2008), 222 pages.

Josianne Paul, "La famille, l’État et les migrations forcées en Nouvelle-France," Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, 2012, 133-6, 70-77, digitized by Persée (https://www.persee.fr/doc/acths_1764-7355_2012_act_133_6_10412).

Robert Prévost, "L'ancêtre des Chassé a choisi l'exil plutôt que la geôle," La Presse, 8 Oct 1994, I13, digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3583085?docref=cQ50LbatnZtmI275dhkIcw&docsearchtext=faux-saunier).

Serge Trinque, " La GABELLE, les FAUX SAUNIERS de la Nouvelle France (dont François Trinquier)," Infos Saint-Guillaume, October 2018, p. 29, digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3583085?docref=cQ50LbatnZtmI275dhkIcw&docsearchtext=faux-saunier).

"Fonds Intendants - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/88995), "Ordonnance de l'intendant Hocquart qui fait défense à toutes personnes venues en ce pays par lettres de cachet d'en sortir sous quelque prétexte que ce soit, à peine contre celles qui seront surprises en leur évasion de trois mois de prison pour la première fois et de peine corporelle en cas de récidive ; pareille défense aux capitaines et maîtres de bâtiments de recevoir sur leurs bords aucuns prisonniers et faux sauniers en quelque endroit qu'ils se présentent dans l'étendue de cette colonie pour s'embarquer et à toutes personnes d'aider et favoriser aucun desdits prisonniers et faux sauniers fugitifs dans leur évasion à peine de cinquante livres d'amende," 10 May 1736, reference E1,S1,D24,P2819, ID 88995.

"Fonds Conseil souverain - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/400803), "Ordonnance du Roi au sujet des faux sauniers destinés pour le Canada qui trouvent les moyens de s'en retourner en France soit par les colonies anglaises ou par les vaisseaux marchands," 14 Feb 1742, reference TP1,S36,P842, ID 400803.