The History of Cholera in Canada

How an ancient disease came to Quebec and Ontario, causing our ancestors to be “scared blue”. Explore this history as seen through the eyes of a genealogist. How did Canadians deal with the 1832, 1834, 1849 and 1854 major epidemics? How did the cities of Quebec, Montreal, Kingston and Toronto deal with the disease?

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Cholera: Canada's 19th-Century Terror

The ancient disease that “scared our ancestors blue"

Cholera in a (Medical) Nutshell

What is Cholera? How is it Transmitted?

Cholera is a severe diarrhoeal disease of the intestine caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium. This bacterium is found in food or water that have been contaminated by faeces from a person infected with cholera. The disease is closely linked to a lack of clean water and crowded, unsanitary conditions.

1850 engraving depicting cramped and squalid housing conditions in London. Credit: Wellcome Images.

What are the Symptoms of Cholera?

After ingesting contaminated food or water, it can take anywhere between a few hours to 5 days for an infected person to show symptoms. Those who develop symptoms are normally afflicted with diarrhoea, which can lead to severe dehydration, shock, and kidney failure. Other symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, muscle spasms and cramps. Left untreated, cholera can kill within a matter of hours. However, most infected people show mild or no symptoms. Though asymptomatic, the cholera bacteria remain in their faeces for up to 10 days, during which time they can transmit the disease to others.

How is Cholera Treated?

Today, cholera is easily treatable with an oral rehydration solution (ORS). Infected persons with severe dehydration may also be given intravenous (IV) fluids or antibiotics to ease symptoms. Unfortunately for our ancestors, these treatments were not available in the 19th century.

How is Cholera Prevented?

Access to clean water and good hygiene practices limit the spread of cholera, including hand-washing, safe food handling, and proper disposal of human waste. Oral vaccines are also effective in preventing cholera.

1832: Cholera Arrives in Canada

Cholera is believed to have originated in the Ganges delta, as early as 400 B.C. The disease was endemic for a very long time in Bengal, located in present-day Bangladesh and western India. In 1817, a particularly devastating epidemic struck Lower Bengal. Cholera started to spread with global trade and ship travel; first through Asia, then Russia, western Europe and finally to the British Isles in 1831. The first death attributed to cholera in Great Britain took place in Sunderland on October 20, 1831. By February of 1832, cholera had made its way to London. The disease had many names: Asiatic cholera, Cholera Morbus, the blue cholera, spasmodic cholera, and Indian cholera, to name a few.

Article appearing in The Essex County Standard on 12 Nov 1831.

Broadsheet warning about Indian cholera symptoms and recommending remedies, issued in Clerkenwell, London, in 1831. Credit: Wellcome Images.

Article appearing in The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post Western Countries and South Wales Advertiser on 21 Feb 1832.

As news of the outbreaks made their way across the Atlantic, fear and panic started to spread in the British colonies.

"Cholera made a massive impact on the imagination of people in the nineteenth century. They feared its sudden, painful, and arbitrary attack. They were horrified by the rapid course of the disease which did not allow a gentle decline into a peaceful death. They were baffled by the pattern of spread of the disease which fitted no known model of contagion. They grew contemptuous of the doctors who could do nothing for the victims and in some places they turned on the doctors and accused them of spreading the disease. The death rate, often approaching 60 per cent of those affected, helped to create panic. 'May the cholera catch you' became a curse." (Bilson, 1980)

The 30,000 inhabitants of Québec City had much to fear. Starting in 1815, the city had been the port of entry for many European immigrants. English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants sailed to Canada in significant numbers. In 1831, 50,000 immigrants entered Canada. The following year, between 70,000 and 80,000 were expected, with the majority arriving at Québec. Some would remain in Lower Canada (present-day province of Québec), while others were expected to travel on to Upper Canada (present-day province of Ontario) and the United States.

In anticipation of cholera reaching their shores, the authorities in Lower Canada took some measures to prevent its propagation. Two boards of health were set up in Montréal and Québec to enforce rules of cleanliness. A quarantine station was also opened at Grosse Île, an island in the Saint-Lawrence River located 46 kilometres downstream from Québec City. Grosse Île was chosen in part for its proximity to Québec City, but mostly because of the isolation it offered as an island.

"La Grosse Île. (Canada) : l'Église catholique et la résidence du surintendant", postcard published between 1904 and 1910, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

At the time of its opening in 1832, Grosse Île's sole objective was controlling the cholera epidemic that arrived by ship. European immigrants were often sailing in cramped and unsanitary conditions. This lack of space and hygiene was the perfect breeding ground for disease.

All ship captains had to anchor at Grosse Île and undergo an examination by a health officer. He then decided whether the ship could continue to Québec. Once at the port in Québec City, the ship would be examined by a medical officer before any passengers were allowed to disembark.

There were many flaws in this system. The medical officer relied on reports from the ship's crew, who could downplay the instances of sickness. Some passengers hid sick family members to avoid a delay in their trip. More importantly, no one knew that someone infected with cholera could be asymptomatic. On the quarantine island, there was no separation of passengers, which meant that sick and asymptomatic persons could be in contact with healthy passengers. The sheer number of immigrants was overwhelming, and the island was soon overflowing with passengers, creating the perfect environment for cholera to spread.

"Québec", 1834 illustration by Alexander Jamieson Russell. Credit: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

The main reason that quarantine failed was that no one knew how cholera was transmitted. There was also no consensus in the medical community on whether an infected person was even contagious. And so, the inevitable happened: cholera arrived in Québec City in June of 1832.

Article appearing in The Evening Post (New York), 15 Jun 1832.

An Unwanted Passenger

Dr. Robert Nelson, health commissioner of Montreal, recorded the first instances of cholera aboard these ships:

The Constantia, sailing from Limerick, arrived on April 28 with 29 deaths on board.

The Robert, sailing from Cork, arrived on May 14 with 10 deaths on board.

The Brubus, sailing from Liverpool, arrived on May 18 with 81 deaths on board.

The Elizabeth, sailing from Dublin, arrived on May 28 with 17 deaths on board.

The Carrick, sailing from Dublin, arrived on June 3 with 42 deaths on board.

On June 7th, the ship Voyageur took a group of the immigrants and their luggage from Grosse Île to Québec and Montréal. As soon as June 8th, cholera was discovered in Québec. Two days later, it was Montréal's turn. From Montréal, passengers soon dispersed throughout Canada with the help of the Emigrant Society. Upper Canada was soon hit by cholera: Kingston, Toronto and Niagara all reported cases. The disease then travelled to the U.S. via the Great Lakes.

The 1832 epidemic caused panic and terror in Canadians. In Lower Canada, cholera gave rise to the expression "avoir une peur bleue" (to be scared blue), in reference to the blue hue left on the corpses of victims. As it became clear that stopping the spread of cholera wasn't going to be possible, people looked for medical advice from apothecaries, the clergy, and medical professionals. Most Canadians, however, could not afford to pay doctors, who mostly worked in urban areas. Hospitals were meant to care for the poor, but most of them had a very limited number of beds and would not admit patients with infectious diseases. Temporary buildings and camps were erected to house the sick.

A young Viennese woman, aged 23, depicted before and after contracting cholera, Coloured stipple engraving, Italy (1831?). Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Cholera Through the Eyes of an Artist

“Cholera Plague, Québec”, painting by Joseph Légaré , circa 1832.

"Here, the cathedral and the houses lining Buade Street provide the backdrop for a scene set in the marketplace of the Upper Town, under a full moon. Sparing no detail, the artist has portrayed an anxious crowd, a cart loaded with corpses, a priest hurrying to the bedside of a dying victim. The theatricality of the image is heightened by the red glow of numerous fires. Légaré, a romantic painter influenced by the many British topographical artists who visited in the city, has captured the horror of the scourge, not to record it but to bear witness to its human impact." (National Art Gallery of Canada)

Causes & Cures

In the 19th century, diseases were still believed to be spread by miasma (unpleasant smells or vapours). Québec City authorities even fired cannons in 1832 to dispel the miasma in the air. In Montréal, artillery was fired to clear the air and rosin was burned at night. These tactics did nothing to prevent the spread of cholera, so many other "cures" emerged. Some doctors prescribed a teaspoon of brandy every hour, believing it was a good stomach stimulant.

"Bottle, Brazill's V O Brandy, F.P.Brazill & Co", 19th century, McCord Museum

Cholera Morbus prescription (undated). Credit: Wellcome Collection.

The first six regulations regarding cleanliness in Montréal (article appearing in The Montréal Gazette on 12 Jun 1832).

Mind Your Hogs

Though the causes of cholera were still unknown, there appeared to be a connection between dirt and the disease. In towns and cities, many houses were small and cramped, often overcrowded. Heaps of garbage were piled on the streets and in people's gardens. Residents drank water from contaminated wells, or worse, from the Saint-Lawrence. The Québec Board of Health soon began to enforce public health regulations through wardens, who went house-to-house for inspections. All dwellings were to be cleaned thoroughly, then purified with lime. New rules were enforced regarding garbage, privies, hogs, the meat industry, and "offensive" trades (like candle- and soap-makers).

New rules were put in place for burials. Anyone who died of cholera during the day had to be buried within 6 hours; anyone dying at night had to be buried within 12 hours. There was little time for mourning and funerals were not allowed. Many bodies were buried in non-consecrated cholera grounds, infuriating loved ones. In Québec, the Saint-Louis cemetery (located at the corner of Grande Allée and De Salaberry) was created to bury cholera victims. It quickly became known as the Cemetery of the Choleric.

Those with means simply fled the cities for the countryside, which, of course, helped to spread cholera even more. By the end of the summer of 1832, most parts of Lower Canada had been affected. The number of cases finally began to drop in the fall. On November 3rd, the epidemic was declared officially over.

The death toll from the 1832 epidemic is difficult to quantify, as estimates from both Lower Canada and Upper Canada varied widely. Recent estimates put the number of deaths at 9,000 to 12,000 for both provinces.

Notre-Dame-de-Québec parish registers, 1832, image 100 of 382. Credit: FamilySearch.

Notre-Dame-de-Québec parish registers, 1832, image 92 of 382. Credit: FamilySearch.

Left: a page from the 1832 parish registers of Notre-Dame in Québec, showing one burial after another at the Saint-Louis cemetery. Most died the same day, or previous day. The entries clearly show that cholera didn't discriminate: among the dead are a day labourer, a joiner, a clerk, a merchant, a seigneur and a judge. Though the cause of death is not listed, the speed at which the dead were buried, and where they were buried, indicate they probably died of cholera.

Above: this entry shows the first mass burial of 54 cholera victims at the Saint-Louis cemetery. All the dead were from the Emigrants' Hospital in Québec. Their names, ages and professions were unknown.

Irish Tragedy: the 1834 Epidemic

Unfortunately for Canadians, respite from cholera was short-lived. In May of 1834, it reappeared at Grosse Île. At first, it seemed to be such a diminished form of the disease that it wasn't thought to be cholera. By July, however, there was no doubt that a second epidemic was underway, albeit less severe than the first. It was only to last a few months, disappearing by September. It was during this second wave of cholera that Grosse Île opened its own parish registers to record baptisms, marriages, and burials. Most of the dead were Irish immigrants.

Excerpt from the Montréal Gazette, 6 Sep 1834.

This parish register entry shows the burial of two Irish boys at Grosse Île, James and Patrick Carrale, aged two and three from County Cork. Grosse-Île parish registers, 1834, image 14 of 265. Credit: FamilySearch.

“Be Temperate in Eating & Drinking!”: the 1849 Epidemic

In 1849, yet another wave of cholera hits Canada. This time, the epidemic didn't come from European immigrants but from the United States, arriving in Kingston, Canada West (present-day Ontario). By June, cholera had arrived in Montréal and quickly spread throughout Canada East. The quarantine station at Grosse Île was still in use, ensuring that any ships coming from Europe were stopped and examined.

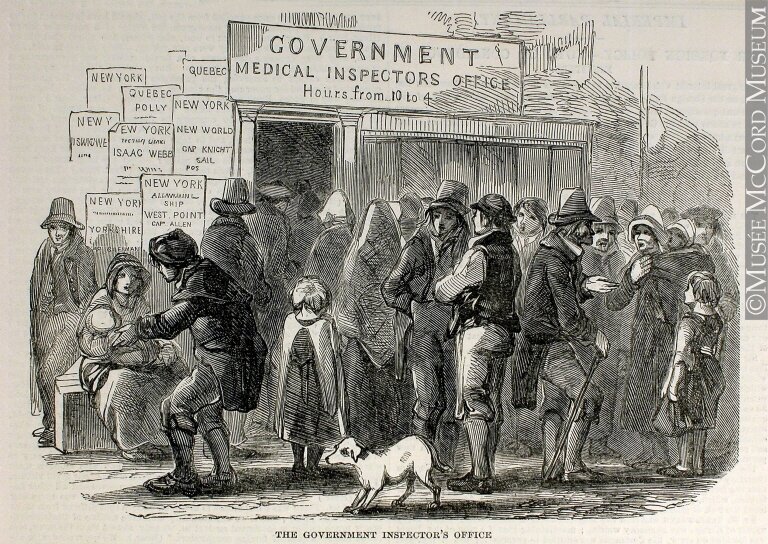

"The government inspector's office", 1850 engraving (artist unknown). Credit: McCord Museum.

By this time, some medical professionals did believe that cholera was contagious, but its method of transmission was still a mystery. They knew it was not contagious in the same sense that smallpox or typhoid was, as evidenced by the many doctors and nurses who treated cholera patients without getting the disease. Those who did not believe cholera was contagious thought the disease was transmitted through people's behaviour or their environment. Everything from dirtiness to anxiety to alcohol was blamed.

Ad appearing in the Montreal Gazette on 7 Jul 1849.

1849 Cholera prevention poster by the Sanatory Committee, under the sanction of the Medical Counsel, in New York City. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Sanitation and hygiene had not improved very much since the epidemics of 1832 and 1834. Cities and towns had no clean water supply or sewage system. Garbage was still discarded in the streets, courtyards, or rivers. Residents got their water from wells, springs, and rivers—sometimes in the very place where sewage was dumped. It was this epidemic that finally convinced Québec City health officials to install an aqueduct for proper water supply (operating as of 1854) and a sewage system.

By the fall, cholera had disappeared. Approximately 1,700 deaths were recorded in the cities of Montréal and Québec from June to October.

Cholera Caused by “Imperfect Drainage and Impure Water”: the 1850s

Cholera did return to Canada in 1851 and 1852 but it was much less severe than in previous epidemics.

On June 17, 1854, the Glenmanna arrived at the port of Québec from Liverpool, having thrown 45 cholera victims overboard during its voyage. Two days previously, it was docked at Grosse Île with another ship, the John Howell. On June 20, passengers from both ships were admitted to the Marine Hospital in Québec and a new cholera epidemic was declared. From there, the disease spread through the city, followed by the towns along the Saint-Lawrence, and those bordering Lake Ontario. Cholera reached Montréal on June 22, Hamilton on June 23 and finally Kingston and Toronto on June 25.

Article from the Ottawa Daily Citizen, 29 Jul 1854.

Letter to the Editor of the Montréal Gazette, 3 Jul 1854.

In its 1854 report, the Central Board of Health attributed the severe spread of the disease to "imperfect drainage and impure water", an indication that they had a better understanding of how cholera spread. The Board recommended "the adoption of thorough drainage, sewerage, and ventilation, with a plentiful supply of pure water, attention to cleanliness, and the prevention of over-crowding." They also made the same recommendations for Grosse Île, along with the segregation of sick passengers.

Cholera was officially declared over in Canada on September 22, leaving an official death toll of 3,486, though today it is believed to have been much higher.

Scientific Breakthroughs: John Snow, Filipo Pacini & Robert Koch

A variant of the original map drawn by Dr. John Snow (1813-1858), a British physician who is one of the founders of medical epidemiology, showing cases of cholera in the London epidemics of 1854, clustered around the locations of water pumps. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1854, the world was one step closer to understanding cholera transmission, when British physician John Snow correctly identified a contaminated water source as the cause of Soho's cholera cases in London. He mapped out cases of cholera and traced them back to the public Broad Street well water pump. After the pump's handle was removed, cases declined dramatically. Another British physician, Dr. R. D. Thomson, did a similar analysis between two neighbourhoods: one obtaining their water from the Southwark Company and one from the Lambeth company. When he studied samples from both, water from the Southwark Company showed high amounts of human excrement, while the Lambeth did not. The neighbourhood supplied by Southwark had 3.5 times more cholera cases.

Around this time, Italian microbiologist Filippo Pacini had successfully isolated and identified the bacterium that caused cholera, by performing autopsies on cholera patients. Through a microscope, he looked at samples from intestines and saw a comma-shaped bacillus that he called Vibrio. Pacini theorized that the bacterium acted on the intestine lining, causing dehydration. He suggested treating patients with injections of salted water. For reasons unknown, his published work was largely ignored by the scientific community, and he wasn't credited with this discovery until well after his death.

A microscope slide prepared by Pacini in 1854, clearly identified as containing the cholera bacterium. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

While studying cholera in India and Egypt in 1883, German microbiologist Robert Koch also identified the bacterium that caused cholera, confirming what had already been shown by Pacini. Miasma theories were finally dismissed.

At the end of the 19th century, many Western European countries avoided severe outbreaks by prevention measures and a clean water supply. In New York, widespread outbreaks were also avoided by accurate diagnosis of the disease in laboratories. As the world finally understood the link between cholera and human waste, a global effort was undertaken to ensure that drinking water was kept clean, and that sanitation was improved.

Crowded dark streets full of dead and dying people, bodies are being loaded on to a cart; representing cholera. Watercolour by Richard Tennant Cooper, circa 1912. Credit: Wellcome Images.

Modern-Day Epidemics

From 1930 to 2011, 115 cases of cholera were reported in Canada. All cases from 1990 were travel-related and imported into the country. A single fatal case was reported from 1992 to 2005. Though Canada is considered cholera-free except for these rare cases, many poorer countries in the world are not. In the last five years, outbreaks have occurred in Sudan, Yemen, Somalia, and Mozambique, just to name a few. The outbreak in Yemen was the deadliest in history, with over a million cases. The lack of safe water and basic sanitation are allowing cholera to flourish in impoverished and under-developed countries. Areas impacted by war, famine, or natural disasters are especially vulnerable.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources & Further Reading:

Barry, Michel. "La Grosse Île : un devoir de mémoire." In Continuité, (85), 40–42. 2000.

Berger, Stephen. Infectious Diseases of Canada. United States: Gideon Informatics, Incorporated, 2020.

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. "Importante épidémie de choléra au Bas-Canada." https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/ligne-du-temps?eventid=141.

Bilson, Geoffrey. A Darkened House: Cholera in Nineteenth-Century Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Cholera - Vibrio cholerae infection." Udated 5 Aug 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/general/index.html.

R. Corbin and R. Lessard. "Le choléra de 1832 : un artisan témoigne." In Cap-aux-Diamants, 2(1), 38–38, 1986. Digitized by Érudit. https://www-erudit-org.res.banq.qc.ca/fr/revues/cd/1986-v2-n1-cd1040467/6500ac.pdf.

Côté-Gendreau, Marielle. "Witnessing history through parish registers: The cholera epidemic of 1832-1834." In Généalogie et histoire du Québec : Le blog de l'Institut Drouin. 13 Apr 2020. https://www.genealogieQuébec.com/blog/en/2020/04/13/witnessing-history-through-parish-registers-the-cholera-epidemic-of-1832-1834/).

LeBlond, Sylvio, M.D. "Cholera in Québec in 1849." In Canadian Medical Association Journal. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1825155/pdf/canmedaj00696-0093b.pdf.

Peters, John Charles. Conveyance of cholera from Ireland to Canada and the United States Indian Territory, in 1832. United States: n.p., 1867.

Pollitzer, Robert. "Cholera Studies. 1. History of the Disease." World Health Organization Bulletin, 10 (1954), 421-461. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2542143/pdf/bullwho00557-0108.pdf.

George Miller Sternberg et al. A Treatise on Asiatic Cholera. United States: W. Wood, 1885.

Taché, Joseph Charles. Mémoire sur le choléra. Ottawa : printed by the Office of Agriculture and Statistiques, 1866. Digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/3254844.

World Health Organization. "Cholera." Updated 5 Feb 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera.

"Report of the Central Board of Health, in Return to the Annexed Address of the Legislative Assembly, 1854." Québec, John Donaghue & Co.: 1855. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-64740790R-bk#page/2/mode/2up.