Smallpox in New France and Canada

Learn how "The Speckled Monster" wreaked havoc on the health of Canadians and decimated Indigenous populations for over 300 years.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Smallpox in New France & Canada:

How "The Speckled Monster" wreaked havoc on the lives of Canadians for over 300 years

Smallpox was a highly contagious disease caused by the Variola major and Variola minor viruses. In French, smallpox is called "variole" or "petite vérole". Centuries ago, it was commonly called "picotte" or "picote", a name derived from the blisters that covered the body (not to be confused with modern-day “picote”, the word commonly used in French Canada to describe chicken pox).

Symptoms

Early symptoms of smallpox were similar to that of influenza. Affected persons could experience fever, headache, vomiting, severe backache and occasionally abdominal pain and delirium. Within two to four days, the fever subsided and a rash began to develop. Smallpox was sometimes called "la mort rouge" (the red death) in reference to the deep red rash.

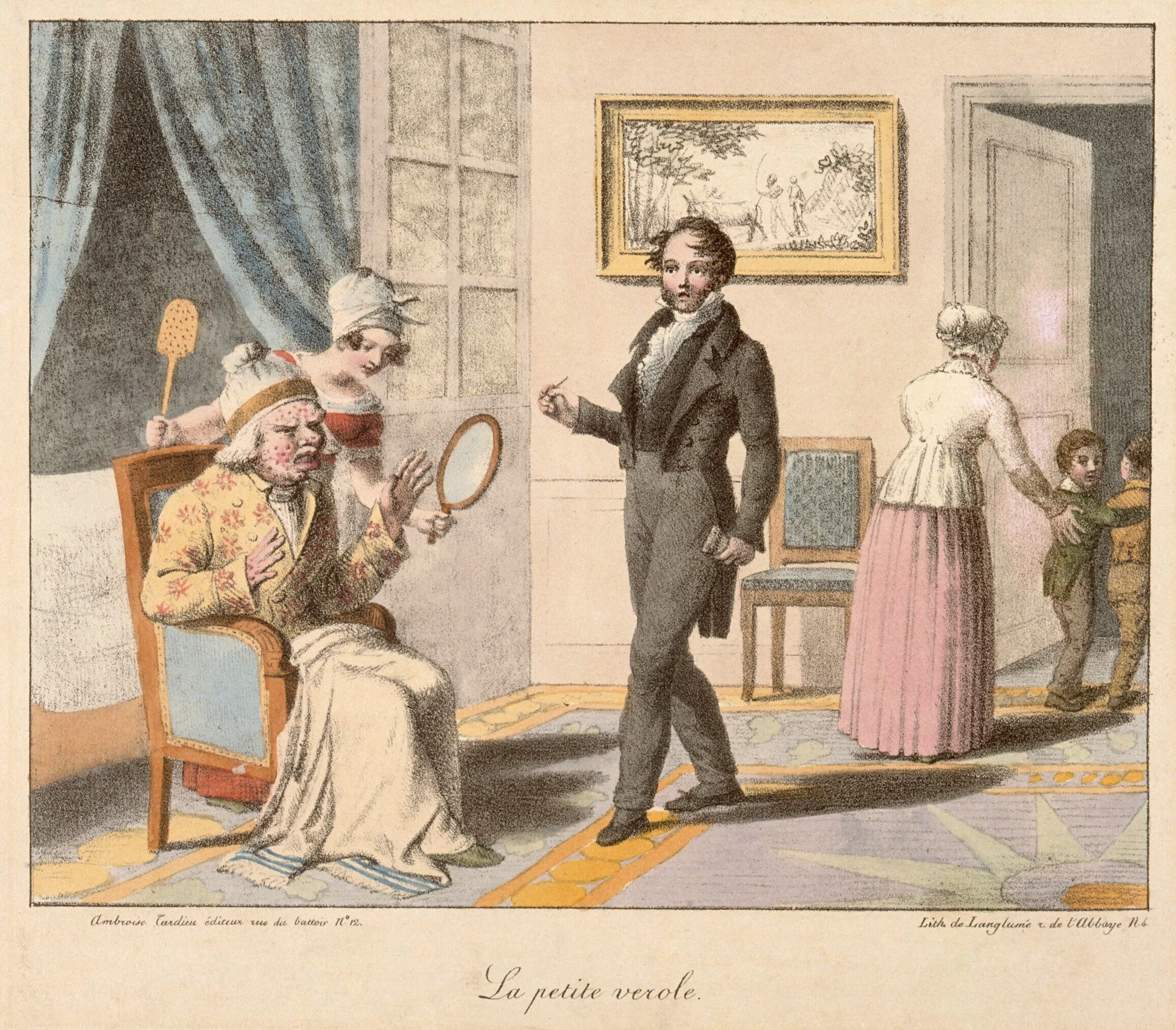

“La Petite Verole”, 1823 coloured lithograph by Langlumé. Source: Wellcome Images.

Rashes and blisters first started to appear in the person's mouth or larynx, then spread to the skin. These macules, papules, vesicles and pustules started on the face and extremities and spread down the body. The blisters ruptured, spreading infected and foul-smelling pus that eventually crusted over. These scabs then separated and fell off in about 3-4 weeks. Underneath, the skin would be pigment-free and would eventually form the pitted scars (or "pocks") characteristic of the disease.

The mortality rate for smallpox was around 30%; those who survived often had permanent scarring and some even lost their sight altogether. It is estimated that in 18th century Europe, 80 to 90% of the entire population had contracted smallpox at some point in their lives.

Transmission

Smallpox was spread through infected droplets or aerosols. Transmission occurred when someone came into direct contact with the droplets or inhaled them, or touched infected rashes or blisters. It could also occur by coming in contact with contaminated objects such as clothing or linens. Historically, smallpox was very contagious. For every infected person, as many as 10-20 additional people contracted the disease from them. It was said that simply being in a patient’s room for a few minutes was enough to catch smallpox.

Smallpox illustration, Japanese manuscript, circa 1720. Source: Wellcome Images.

Origins

Smallpox is believed to have originated in East Asia, then spread to the Middle East, India, Africa and Europe. In the 16th century, it appeared in the Americas, first striking the West Indies in 1507, probably introduced by Spanish sailors. As we'll see with New France, smallpox was especially devastating to the native populations in South and Central America.

It took another century before smallpox would reach the shores of New France.

Frequent Epidemics in New France

“Huron Indian”, circa 1780 engraving. Source: BAnQ numérique.

The first epidemic in New France struck a trading post near present-day Tadoussac in 1616. Brought there by French settlers, smallpox decimated the native Innu ("Montagnais") and Algonquin population who had no natural immunity to most European diseases. From Tadoussac, the disease spread to other native populations in the Maritimes, James Bay and the Great Lakes. In 1639, the disease led to the death of 60% of the Huron-Wendat indigenous peoples, likely introduced by Jesuit priests. From 1663 to 1665, the Haudenosaunee ("Iroquois") were hit hard by the disease. 1,300 died, 300 of them children, and villages were left abandoned.

Smallpox reappeared around 1670-1680, almost wiping out the entire community of the Atikamekw nation who lived along the Saint-Maurice river. It then spread to the Haudenosaunee, Algonquins and Innu. In the winter of 1669-1670, smallpox reached the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, near Tadoussac, Île Verte and Sillery. The Algonquins, Innu and Opâpinagwa (“Papinachois”) nations were affected, with over 250 deaths. The trading post at Tadoussac was all but abandoned. For the remainder of the 17th century, smallpox was almost always present within Indigenous groups, who unintentionally spread the disease as they travelled and traded with other nations.

At the turn of the 18th century, smallpox severely affected the Canadian non-Indigenous population for the first time. Most of the Canadian-born inhabitants, like the indigenous population, had no natural immunity to the disease. In 1699, a smallpox epidemic killed more than 100 people in New France. In November of 1702, another epidemic began in Québec City, thought to have been introduced by an Indigenous man coming from Orange (Albany, New York). At that time, smallpox was ravaging New York and England. It rapidly spread to the rest of the colony, leaving 2,000-3,000 people dead, indigenous and non-indigenous alike. The 1702-1703 winter epidemic is thought to be the deadliest smallpox epidemic for the non-Indigenous population in New France. Half of the total population was affected and around 10% of inhabitants died within six months.

“A New chart of the coast of New England, Nova Scotia, New France or Canada with the islands of Newfoundl[an]d, Cape Breton, St. John's etc.”, appearing in the 1746 Gentleman's Magazine [Louisbourg is highlighted in red]. Source: BAnQ numérique.

After a few decades of respite, yet another epidemic occurred in 1732-1733. An outbreak originating in Boston hit Louisbourg, on present-day Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia. Nearly 200 people died, many of them children. The rest of New France also suffered from a smallpox epidemic during this time.

From 1755 to 1775, smallpox struck again. This epidemic even affected the Seven Years' War, derailing captain Vaudreuil's military plans to attack New England. Over 2,500 cases were reported in Québec City in the first two years, with a mortality rate approaching 20% of the city. The smallpox that ravaged the country during this two-year period is considered the worst smallpox epidemic in Canadian history.

“Smallpox prevails in the cities and rural districts, few houses are exempt from it.”

Incredibly, smallpox may have been used as a biological weapon against Indigenous people in the 1760s. Correspondence uncovered between Jeffery Amherst, commander in chief of the British forces in North America and one of his colonels, discuss the tactic of giving contaminated blankets to the Indigenous. We don't know for certain that Amherst's directives were followed, but the outrage it caused in recent years was enough to see Amherst's name removed from a Montreal street. It is now called Atateken Street, meaning "brothers and sisters" in the Kanienʼkéha language.

Ad appearing in The Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh) on 25 May 1765

Variolation

Shortly after New France was surrendered to Great Britain in 1763, the concept of variolation was introduced to the world (in the 18th century, variolation was also called "smallpox inoculation", not to be confused with today's use of "inoculation", used interchangeably with "vaccination"). The basic theory was that a person who had contracted smallpox wouldn't be able to get it a second time. A small scratch on the arm was seen as the most effective way of exposing people to a less severe form of the virus. Variolation was widely used in Europe in the mid-18th-century. It eventually made its way to Quebec, used by upper-class families, as well as the British troops stationed there.

The Quebec Gazette from 12 Oct 1769 featured this news: "The smallpox rages here with great violence and is extremely fatal, scarce a Day passes without six or seven Persons dying. It is to be hoped that the Fatality will soon cease, as the Canadian Inhabitants have at last approved of Inoculation [variolation], owing to the judicious advice of their Clergy, and by seeing the easy and successful Suttonian method, practiced here by Mr. Latham, Surgeon to the King's (or 8th) Regiment of Foot, Montreal."

In 1775, smallpox even played a major role in thwarting an invasion of Québec by George Washington and his troops. Washington attempted to variolate his men in Boston prior to their departure, but he had waited too long. By the time the army was poised to attack, many of Washington's men had already contracted smallpox and were too sick to continue. British troops, on the other hand, were all immunized. Washington was forced to retreat.

In Québec City, a new cimetière des picotés (smallpox cemetery) was established in 1779 near the Hôtel-Dieu [located at present-day Hamel Street in Old Québec]. It would be utilized until 1857 before being abandoned. Smallpox hit once again in 1783, with 1,000 people dying in Québec city alone. This epidemic spread throughout the entire colony.

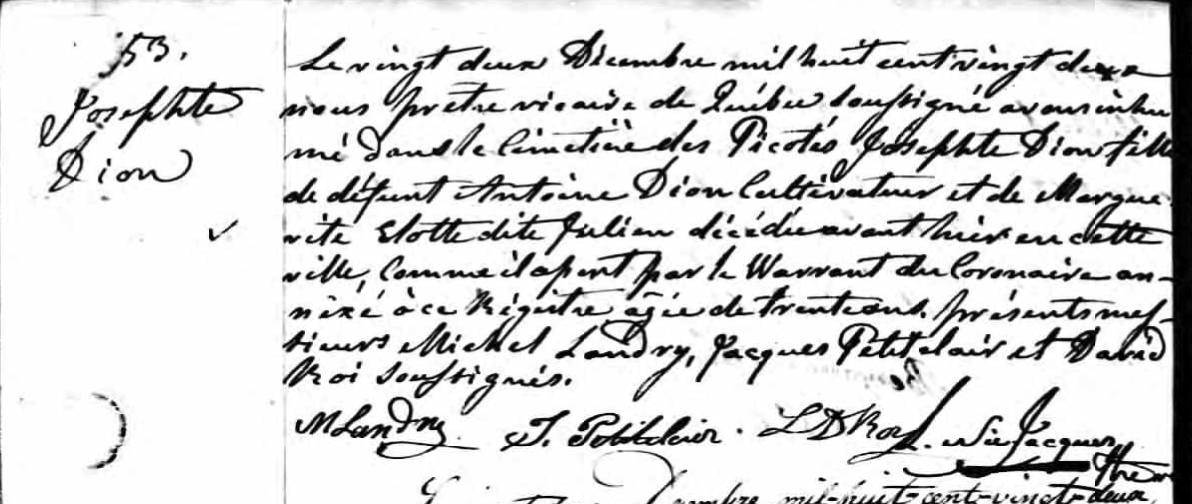

The 1822 burial record of Josephte Dion, showing she was interred in the “Cimetière des Picotés” (Smallpox Cemetery)

Vaccination, Riots and Eradication

A smallpox vaccine was introduced to North America in 1798 by Edward Jenner. It was the first successful vaccine ever developed. In 1801, it was available in Lower Canada (the present-day province of Québec). The first people to be vaccinated were the children of Captain William Backwell, vaccinated by colonel George Thomas Landmann in Québec City.

Coloured etching, circa 1800. Source: Wellcome Images.

In this cartoon, the British satirist James Gillray caricatured a scene at the Smallpox and Inoculation Hospital at St. Pancras, showing cowpox vaccine being administered to frightened young women, and cows emerging from different parts of people's bodies. The cartoon was inspired by the controversy over inoculating against smallpox. Source: Library of Congress.

After Confederation in 1867, Canadian provinces made it mandatory to vaccinate schoolchildren. Laws were also put in place to allow municipalities to enforce mandatory vaccination if an epidemic was imminent. Though most health advocates urged everyone to get the vaccine, there was strong resistance by anti-vaccinationists ("anti-vaxxers" in today's terminology) throughout the 19th century, especially in Montreal.

In 1885, a devastating smallpox epidemic hit the city. The disease came to Montreal in February on the Grand Trunk Railway and one of its conductors, George Longley, who had caught it in Chicago. After arriving at Bonaventure station with a high fever and a red rash, he was sent to the Montreal General Hospital (since he was a Protestant). A physician diagnosed him with smallpox, and then refused to admit him to the hospital. Longley was sent to the Hôtel-Dieu instead, where he was given a room. Though he survived his ordeal, Longley infected the hospital staff that cleaned his linens. The first victim was an Acadian girl named Pélagie Robichaud, who worked in the laundry. She died shortly after Longley’s arrival, following by her sister. Soon smallpox was rampant in the hospital and it quickly spread to the streets of Montreal.

Paragraph appearing in the Gazette on 7 Sep 1885

The 1885 epidemic resulted in over 5,864 deaths and 20,000 affected. Despite the high mortality rate, many French Canadians resisted the city's mandatory vaccination order. They were highly skeptical of the government, refusing any measures to control them or "poison their children". In retaliation, some English newspapers published racist articles blaming the French for the outbreak and calling them backward and unclean. Some French Canadian doctors further complicated the situation by expressing skepticism at the vaccine, with some even forming la Ligue contre la vaccination obligatoire (The League Against Mandatory Vaccination). The epidemic, coupled with the trial of Métis leader Louis Riel, led to street riots in Montreal putting French and English Canadians on opposite sides. Even sanitation workers attempting to remove bodies from the worst-affected neighbourhoods were attacked by mobs. 9 out of 10 victims who lost their lives were French Canadian, most of them children.

Sanitary police removing smallpox patients from the public. Sketch by Robert Harris published in Harper’s Weekly on 28 Nov 1885. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Article in The Gazette (Montreal) from 22 Sep 1885

Article in The Gazette (Montreal) from 24 Sep 1885

A doctor leans over and pricks the arm of a seated woman in a train car. The illustration was initially published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper on 26 December 1885 by author James Marvin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ad appearing in the Gazette, 21 Aug 1885

Ad appearing in L'Étoile du Nord, 17 Oct 1885

Article appearing in Le Courrier du Canada, 24 Oct 1885

On September 28 and 29, 1885, riots broke out in Montreal in reaction to the municipal council's directive to be vaccinated against smallpox. Source: BAnQ numérique.

Smallpox victim in Prince Edward Island, circa 1909. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Smallpox vaccine production began in Canada in 1916. Despite this, the disease persisted until 1946, when vaccination campaigns were finally successful in eliminating it

In the 1960s, the World Health Organization (WHO) spearheaded a worldwide inoculation campaign aiming for 80% coverage in all countries, followed by targeted vaccination. It declared smallpox eradicated in 1980, following two years without any cases worldwide. The very last case occurred in Somalia in 1977.

To date, smallpox is the only human disease to have been successfully eradicated by vaccines.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources and Further Reading:

Terry Crowley, Louisbourg: Atlantic Fortress and Seaport, The Canadian Historical Association, 1990, Historical Booklet No. 48, page 13 (https://cha-shc.ca/_uploads/5c38c5cc4dccb.pdf).

John Joseph Heagerty, Four centuries of medical history in Canada and a sketch of the medical history of Newfoundland (Toronto : Macmillan Co. of Canada, 1928), uploaded to Archive.org on 25 Apr 2014 (https://archive.org/details/fourcenturiesofm00heag).

Patrick J. Kiger, " Did Colonists Give Infected Blankets to Native Americans as Biological Warfare?", 15 Nov 2018, History.com (https://www.history.com/news/colonists-native-americans-smallpox-blankets).

Yves Landry & Rénald Lessard, "Les causes de décès aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles d’après les registres paroissiaux québécois", 1995, Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 48 (4), 509–526, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/305363ar).

Rénald Lessard, " L'épidémie de variole de 1702-1703, une tragédie", Le Journal de Québec (https://www.journaldequebec.com/2020/04/26/photos-lepidemie-de-variole-de-1702-1703-une-tragedie).

Gisèle Levasseur, S'allier Pour Survivre. Les épidémies chez les Hurons et les Iroquois entre 1634 et 1700 : une étude ethnohistorique comparative, 2009, Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval (https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/bitstream/20.500.11794/20978/1/26238.pdf).

James H. Marsh, "The 1885 Montreal Smallpox Epidemic", The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2 Apr 2013, Historica Canada (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/plague-the-red-death-strikes-montreal-feature)

Laurianne Petiquay , "L'histoire des Atikamekw", Centre Administratif Wemotaci, Archived from the original on 2017-12-21 (https://web.archive.org/web/20171221013634/http://www.wemotaci.com/histoire.html).

Christopher J. Rutty, "A Pox on our Nation", Feb-Mar 2015, Canada’s History, digitized on 7 Apr 2020 on Canada's History (https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/science-technology/a-pox-on-our-nation).

William B. Spaulding and Maia Foster-Sanchez, "Smallpox in Canada", The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 Feb 2006, Historica Canada (https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/smallpox).

“Début de la vaccination dans le Bas-Canada”, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, BAnQ numérique (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/evenements/ldt-46)

"Diseases: Smallpox", Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Government of Ontario, (http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/pub/disease/smallpox.html).

"Épidémies à Québec au XVIIIe siècle", Histoire du Québec (https://histoire-du-quebec.ca/epidemies-a-quebec-au-18e-siecle/)

"Les « fièvres » — Épidémies chez les Amérindiens du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle en Nouvelle-France et dans le Nord-Est américain", Bulletin STATLABO — 2017, vol. 16, n° 1, Institut national de santé publique du Québec (http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/bs2750545).

"Smallpox vaccines", World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/csr/disease/smallpox/vaccines/en/).

"Vie quotidienne: Santé et médecine", Musée canadien de l'histoire (ttps://www.museedelhistoire.ca/musee-virtuel-de-la-nouvelle-france/vie-quotidienne/sante-et-medecine/), recherche originale par Stéphanie Tésion, Ph.D.

![“A New chart of the coast of New England, Nova Scotia, New France or Canada with the islands of Newfoundl[an]d, Cape Breton, St. John's etc.”, appearing in the 1746 Gentleman's Magazine [Louisbourg is highlighted in red]. Source: BAnQ numérique.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb6661d8dfc8c1836526d3a/1600209499650-RCMLHPMHGT9QQ3QUQSNN/History+of+Smallpox+in+New+France+and+Canada)