Tuberculosis in Canada

Learn how an ancient disease became known as "The White Plague" and Came to be the Deadliest Disease in Canada.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Tuberculosis

How the “White Plague” Became the Deadliest Disease in Canada

What is Tuberculosis?

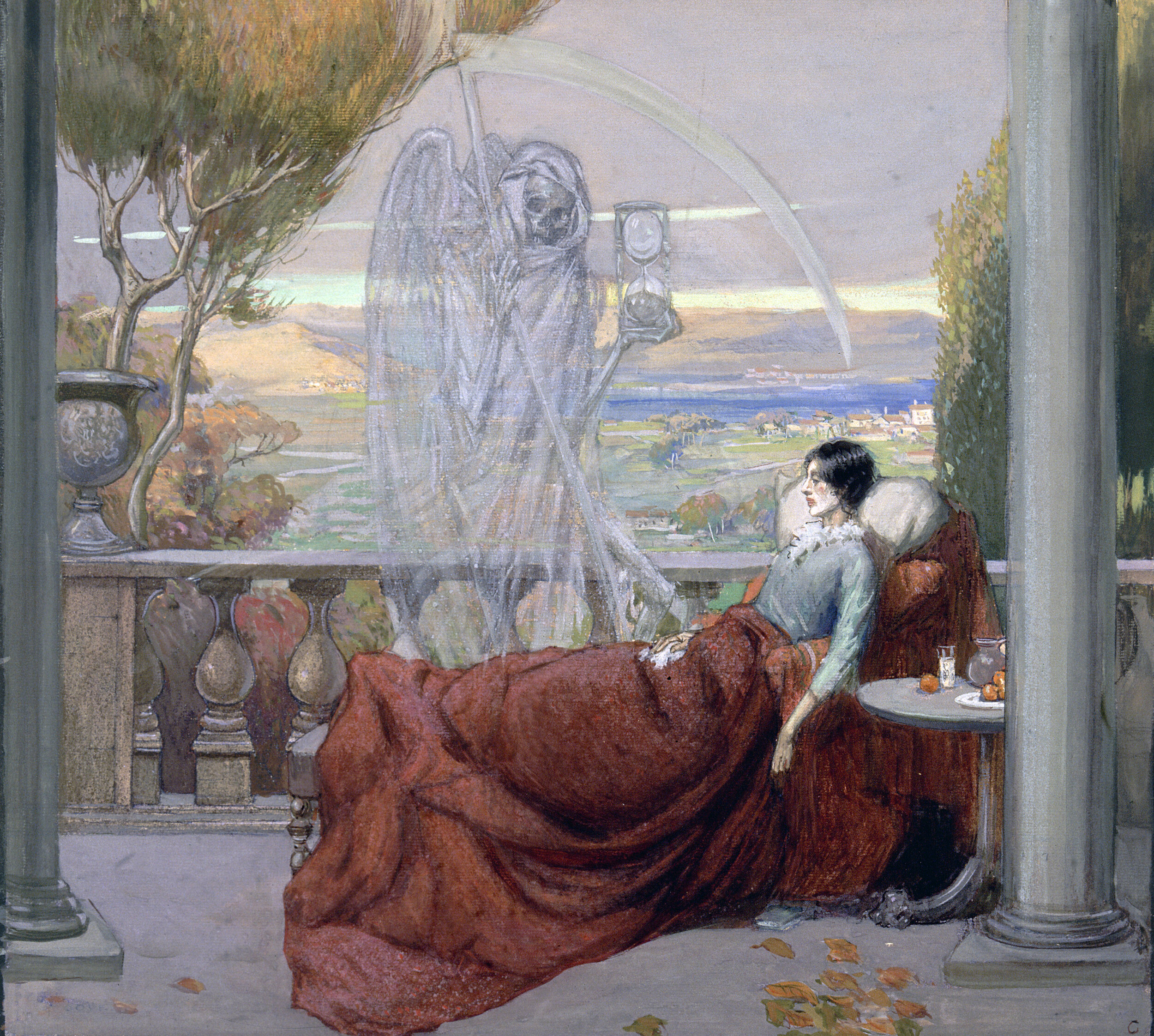

A sick woman lies on a balcony, with death standing next to her, representing tuberculosis. Watercolour by Richard Tennant Cooper. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a very old infectious disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may have originated in cattle. Though the term "tuberculosis" was coined in 1834, the bacteria that causes it is thought to have been around as long as 3 million years ago. Even so, TB has only become the deadliest of the world's contagious diseases in the last three centuries.

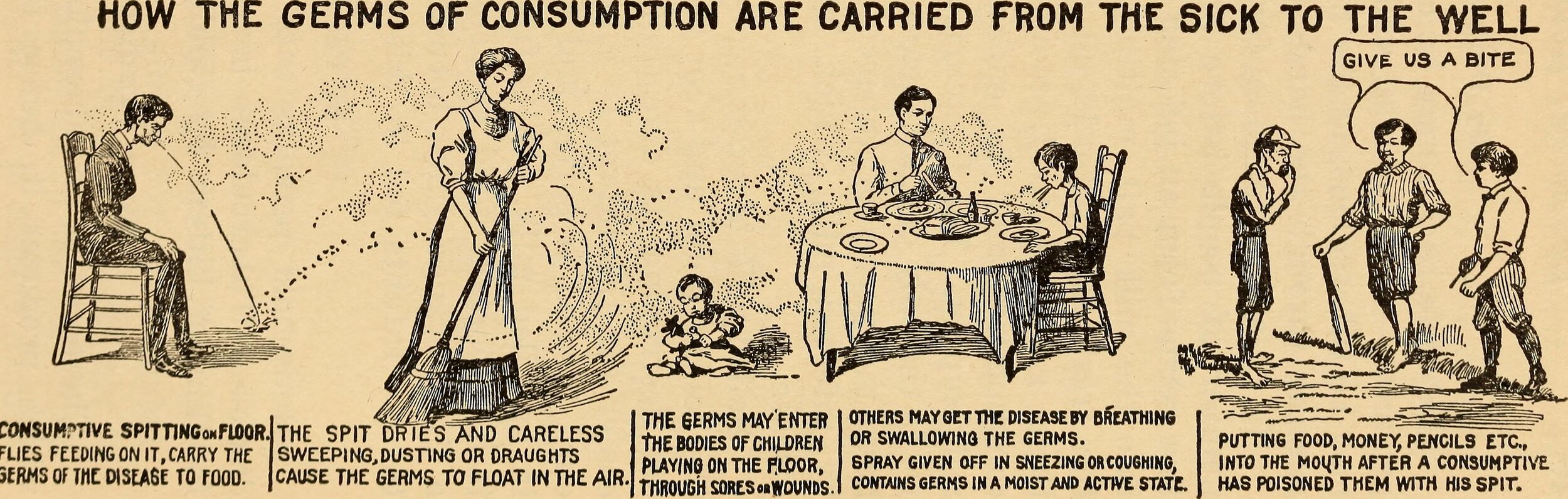

TB is spread through the air. When an infected person coughs, sneezes or spits, their droplets can infect someone who inhales them. Once in the body, TB bacteria can attack any part of the body, such as the skin, bones, joints, eyes and the brain, but it primarily affects the lungs. Once TB infects the throat or the lungs, it becomes contagious and can be spread to other people. However, not everyone infected with TB bacteria gets sick. There are two types of TB: latent TB and TB disease. People with latent TB may never develop TB disease if the TB bacteria remains inactive. If the immune system of an infected person cannot fight the TB bacteria, it can spread and cause TB disease.

The symptoms of TB vary as the disease progresses. Initially, the infected person experiences fatigue and fever, as well as night sweats, coughing and weight loss. Then, their voice will because hoarse and their breathing will accelerate. They will cough up sputum, and sometimes blood due to the rupture of vessels. Fever continues, followed by extreme weight loss and finally chest pains.

“The Spread of Consumption”. Image from Epidemics: How to Meet Them, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, 1919, page 45.

Article appearing on page 2 of the Meridional (Abbeville, Louisiana) on 27 May 1882.

A Long History

Historically, researchers had identified three main forms of TB disease since antiquity. The first was identified in Egypt, where mummies were discovered with skeletal deformities in their spinal column (later called Pott's disease). Skeletons with similar deformities were also found in the Americas. In the Middle Ages, TB manifested itself through scrofula, or the infection of neck glands with pus discharge. The third form of TB occurred in the 17th century: pulmonary tuberculosis. In the century that followed, the disease ravaged cities like London, where one in four deaths were attributed to TB. It was the primary cause of death among adults. German scientist Robert Koch finally discovered the TB bacteria in 1882, for which he won the Nobel prize.

The “King's Evil” or a “Romantic Disease”?

Historically, tuberculosis was called a variety of names. In Ancient Greece, it was called "phthisis". In the Middle Ages, it was called "scrofula". In the 16th century, TB was the "King's Evil", which could be cured by the "King's Touch". The term "White Plague", named for the paleness of the infected, was used in the 18th century. Though the term "tuberculosis" was already in use, TB was commonly called “consumption” in the 1800s. Consumption got its name because the disease appeared to "consume" the infected person's body, through dramatic weight loss. Perhaps the most surprising of all names, TB was also called the "romantic disease", associated with great artists and writers of the Victorian era. Compared to other diseases of the time, TB's side-effects were considered flattering: pale skin, rosy cheeks and small waists.

The Sick Child: oil paining by Edvard Munch, 1885–86, depicts the illness of his sister Sophie, who died of tuberculosis when Edvard was 14; his mother too died of the disease. Credit: National Gallery of Norway.

The King’s Touch: Henri IV of France touching the head of a kneeling man for the king's evil. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

In Québec, tuberculosis was known as “phtisie pulmonaire” (pulmonary phtisis). By the end of the 18th century, the term “consomption pulmonaire” (pulmonary consumption) was being used.

The notebook of Dr. Jean-François-Régis Latraverse, describing the death of Adèle Lavallée on 1 Oct 1880 from “consomption” (consumption). Source: BanQ numérique (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/299294).

Tuberculosis in New France and Canada

Tuberculosis is believed to have landed in New France in the 17th century with the arrival of Europeans. With each new wave of immigrants came more TB, which eventually reached Canada's indigenous communities as well. As with many other diseases such as smallpox and measles, tuberculous was devastating to indigenous populations, who had no natural immunity to the disease. By the mid-19th century, the disease had spread all the way to Canada's western shores.

Though tuberculosis was present in the early days of New France, it only wreaked havoc on the Canadian population (of European descent) in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1867, TB was the leading cause of death in Canada. Between 1896 and 1906, TB was the deadliest infectious disease in the province of Québec, killing over 33,000 people. The reasons for the high casualty rate were attributed to urbanization and industrialization. Most infected people lived in urban areas and worked in factories, where proper hygiene was lacking. Milk was also believed to be a culprit. In Québec, veterinarians estimated that 10% of cows were infected with bovine TB and producing infected milk. In 1914, only a quarter of Montreal's milk was pasteurized; pasteurization became mandatory in 1925.

Guaranteed Pure Milk Company delivery wagon, Montreal, about 1910. “At this time, only better-off people living in the west end of the city could get pasteurized milk, delivered on wagons like the one shown here. This photograph shows a milkman in front of the company's head office and processing plant on Ste. Catherine Street West. From its plant in the west end of Montreal, the Guaranteed Pure Milk Company distributed its milk in the wealthy neighbourhood known as the Golden Square Mile”. Credit: McCord Museum.

In the 19th century, the upper classes of Canadian society believed that the lower classes were contracting TB through their own doing: they lived in unclean dwellings, didn't eat proper food and led unwholesome lifestyles. Alcoholics were also accused of spreading the disease.

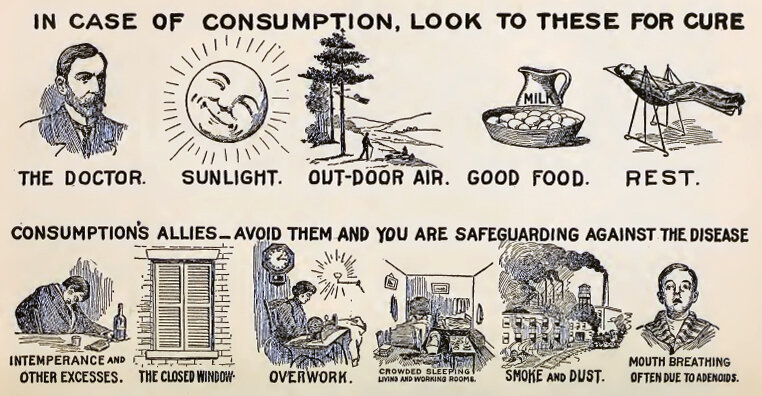

"Cures and Causes": image from Epidemics: How to Meet Them, Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington, 1919, page 44.

“Her Own Fault”

In Ontario, the Provincial Board of Health sponsored a 1921 silent film called “Her Own Fault”. In it, Marnie, “the girl who fails in life’s struggle,” sleeps in a stuffy and messy room with closed windows. She "never goes near the bath" and spends too much time on hair, makeup and fashion. Marnie also has poor eating habits and rarely exercises, except for late-night foxtrot sessions. Eileen, “the girl who succeeds,” wakes up in an airy and clean room. She makes sure to bathe and eat a healthy breakfast. Eileen exercises and counts her calories. "Months later both girls get what was coming to them". Marnie ends up hospitalized with tuberculosis, while Eileen is promoted to forewoman at the factory.

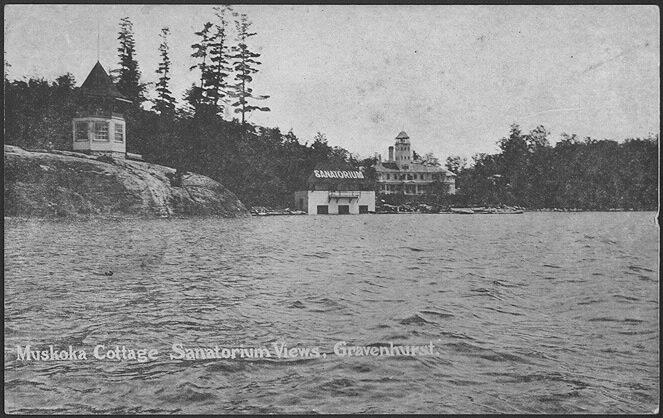

These cultural opinions changed considerably after the end of WWI. Medical news coming from Europe made it clear that bacteria was causing TB, not bad behaviour. Any infected person essentially became a pariah that had to be isolated. This led to the opening of several sanatoriums, where patients could remain in isolation. In Ontario, the first sanatorium opened in 1897 in Gravenhurst. This facility, the Muskoka Cottage Sanatorium, was the third tuberculosis sanatorium in the world. In Québec, the first sanatorium opened in 1907 in Ste-Agathe-des-Monts. Most sanatoriums were run by volunteer organizations, whose members were often part of society's elite. Initially, only wealthy patients could afford a sanatorium stay. Eventually, care was offered to those who couldn't afford it, mostly through donation campaigns. One of the most important organizations was the Canadian Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, founded in Ottawa in 1900 (today, it is called the Canadian Lung Association). It focused on public education and helped to open sanatoriums and dispensaries.

Canadian Sanatoriums

Muskoka Cottage Sanatorium in Gravenhurst, Ontario. 1910 Postcard. Credit: Toronto Public Library.

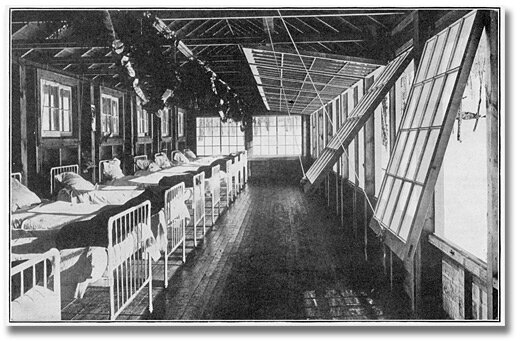

Interior view of Kendall Pavilion of the Muskoka Cottage Sanatorium, showing arrangement of glass front. Circa 1928. Credit: Archives of Ontario.

Sanatorium de Ste-Agathe des Monts. Photo taken between 1920-1930. Credit: BAnQ numérique.

The Anti-Tuberculosis Hospital of the Royal Ottawa Sanatorium. Undated photo by William James Topley. Credit: Library and Archives Canada.

In 19th- and early 20th-century Canada, there were two main treatments for TB. The first was called the "rest cure", in which infected persons were placed in a sanatorium, where they could get fresh air, bed rest and a good diet. Most patients remained in the sanatorium for a period of 6 months to 2 years. The second treatment was "collapse therapy", in which a patient's chest cavity was inflated with air, allowing the lung to relax and the TB lesion to heal. Roughly one third of patients received this form of treatment.

National efforts were spearheaded to prevent the spread of TB: food-quality legislation was passed, public education was rolled out and TB dispensaries were opened. Dispensaries provided food, clothing, sputum boxes and medicine. In 1911, a free dispensary was opened in Toronto, providing these goods free of charge, in addition to paying the rent of deserving TB patients. Similar to sanatoriums, these dispensaries were often run by volunteers, on donations.

Envelope asking for donations to the Muskoka Free Hospital for Consumptives, 1908. Credit: Toronto Public Library.

Clipping from unidentified newspaper indicating staff of Albert’s Bakery free from tuberculosis. 1944, Timmins. Credit: Archives of Ontario.

In the 1920s, mobile TB clinics were created, allowing for quicker diagnosis and treatment of TB patients. Mobile x-ray machines were used to find TB before external symptoms appeared. In 1929, Saskatchewan offered free diagnosis and treatment to all of its residents, the first jurisdiction in North America to do so. Soon, there were sanatoriums and dispensaries in every province. By 1953, Canada had 101 sanatoriums nationwide.

French Ministry of Public Health poster promoting BCG vaccination

Vaccine & Antibiotics

In 1924, the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine was introduced in France. It was not widely used in Canada, however. Only Newfoundland and Québec administered the BCG vaccine in mass vaccination campaigns. Influenced by negative opinions in the U.S. about the efficacy of the BCG vaccine, other provinces used it sparingly. Today, BCG vaccination is only recommended for at-risk babies and children (for example, those born in areas with high TB rates).

Streptomycin, the first antibiotic proven to kill TB bacteria, was discovered in 1944. By the 1950s, this drug, along with several others provided free of charge, were widely used to treat TB in Canada. Once effective antibiotics were discovered, the need for sanatoriums decreased. The last Canadian sanatorium closed in the 1970s.

Does Tuberculosis Still Exist Today?

After WWII, with improved hygiene measures and antibiotics, TB became manageable and death rates declined substantially. Though it still exists today, TB is both preventable and curable.

Incredibly, about a quarter of the world's population currently has latent TB, meaning that they haven't developed the disease yet and cannot infect others. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 5-10% of people with a TB infection will actually develop the disease over their lifetime, accounting for 9 to 10 million new cases annually.

Though TB can occur in any part of the world, two-thirds of cases today are located in India, Indonesia, China, Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa. As with other developed countries, there are very few cases in Canada annually. However, the incidence of TB among First Nations people, Inuit people, and those born outside of Canada is still disproportionately high. Since the 1970s, Lac Brochet and several other First Nations communities in northern Manitoba, have recorded some of the highest rates of TB in the world. Rates of TB in First Nations communities are 8 to 10 times higher than the Canadian average.

Inuit Numbered for Tuberculosis. Undated photo. Credit: Canada. Dept. of Transport / Library and Archives Canada.

If someone in Canada does contract TB, they are obligated to report it. In the province of Québec, it is the only infectious disease that requires mandatory treatment. To cure TB, an infected person must take antibiotics for 4-6 months, normally a combination of 2, 3 or 4 different drugs. Without treatment, half of those infected with TB will die within 5 years.

Did you know that Nelson Mandela, Jane Austen, Ringo Starr and Robert Burns have all had tuberculosis? Throughout history, many notable Canadians also suffered from, or died of, tuberculosis. See a complete list here.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources and further reading:

Bailey, Patricia G., and Norman C. Delarue, and Howard Njoo, "Tuberculosis". In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. 7 May 2008; Edited 17 Feb 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/tuberculosis

Bernier, Jacques. Médecine et idéologies. La tuberculose au Québec, XVIIIe-XXe siècles. Québec : Les Presses de l'Université Laval. 2018. https://www.pulaval.com/libre-acces/9782763739519.

Grzybowski, Stefan and Edward A. Allen. " Tuberculosis: 2. History of the disease in Canada". 6 Apr 1999. Canadian Medical Association Journal (https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/160/7/1025.full.pdf).

Macdonald, Mary Ellen, et. al. "Urban Aboriginal Understandings and Experiences of Tuberculosis in Montreal, Quebec, Canada". 8 Feb 2010. Qualitative Health Research (http://qhr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/20/4/506).

Newland, Christina. "The Prettiest Way to Die: Consumption Chic and the 19th-Century Cult of the Invalid". 3 Oct 2017. Lit Hub (https://lithub.com/the-prettiest-way-to-die/).

Pepperell CS, et al. "Dispersal of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via the Canadian fur trade". 2011. National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3080970/).

Skerritt, Jen. "TB Epidemic Plagues the North". 31 Oct 2009. Winnipeg Free Press (https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/special/TBspecial/TB-epidemic-plagues-the-North-66561007.html).

"History of Tuberculosis", Canadian Public Health Association (https://www.cpha.ca/history-tuberculosis).

"Ontario's Tuberculosis Sanatoriums, 1897-1960", 18 Apr 2019, Toronto Public Library Blog (https://torontopubliclibrary.typepad.com/local-history-genealogy/2019/04/ontarios-tuberculosis-sanatoriums-1897-1960.html).

"Tuberculosis", World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis).

"Tuberculosis", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm).