Zacharie Cloutier & Sainte Dupont

Zachary Cloutier and Sainte Dupont are the most prolific immigrants to settle in New France. Learn about their journey, legacy, and lasting impact on Québec's history. Explore their role in shaping early Canada, their famous descendants, and the places that commemorate them today.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Zacharie Cloutier & Sainte Dupont

Canada’s most prolific immigrants

Zacharie Cloutier and Sainte Dupont were among the most influential settlers of New France, playing a key role in establishing and populating what would become Québec. If you have French-Canadian ancestry, there’s a strong chance you’ll find them in your family tree—possibly more than once. As some of the earliest colonists, they had six children, five of whom survived to adulthood and started families of their own. By the early 19th century, Québec parish registers recorded 10,850 marriages among their descendants—more than any other early colonial family.

Origins in Mortagne-au-Perche

Zacharie Cloutier (sometimes spelled Cloustier) was born around 1590 in Mortagne-au-Perche, Perche, France, the son of Denis Cloutier and Renée Brière. His father was likely a joiner and ropemaker. Zacharie was one of nine children.

Sainte Dupont (sometimes spelled Xainte) was born around 1596 in the same town. She was the daughter of Paul-Michel Dupont and Perrine (maiden name unknown).

Location of Mortagne-au-Perche in Normandy, France (Mapcarta)

Mortagne-au-Perche, located about 135 kilometres west of Paris, is in the present-day department of Orne in the region of Normandy. During the 17th century, it was a bustling market town known for its skilled artisans, particularly carpenters, joiners, and stonemasons—trades that would prove invaluable in New France. It was also a key centre for emigration to Canada, with several families leaving for the colony under the recruitment efforts of Robert Giffard. Today, the town has a population of about 4,000 residents, called Mortagnais, and maintains strong ties to its French-Canadian heritage.

Postcard of Mortagne-au-Perche, circa 1900-1925 (Geneanet)

Postcard of Mortagne-au-Perche, 1910 (Geneanet)

Marriage and Family

1616 marriage of Zacharie and Sainte (Direction des archives et du patrimoine culturel de l'Orne)

Sainte Dupont first married Michel Lermusier in the parish of Saint-Jean in Mortagne-au-Perche, on February 26, 1612, at about 16 years old. The couple had no known children, and Lermusier died shortly after the wedding.

On July 18, 1616, Sainte married Zacharie Cloutier in the same parish. He was about 26 years old, and she was about 20.

Their six children were born and baptized in Mortagne-au-Perche:

Zacharie (1617–1708)

Jean (1620–1690)

Sainte (1622–1632)

Anne (1626–1648)

Charles (1629–1709)

Louise (1632–1699)

Postcard of Mortagne-au-Perche, before 1887 (Geneanet)

Voyage to the New World

Zacharie Cloutier’s journey to Canada began on March 14, 1634, when he and master mason Jean Guyon du Buisson signed a contract with Robert Giffard, seigneur of Beauport and recruiter for the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. Giffard was seeking skilled tradesmen to help build and expand the struggling colony, and Zacharie’s reputation as one of Mortagne-au-Perche’s finest carpenters made him a valuable recruit. Under the contract, he agreed to work in New France for three years as a master carpenter, land clearer, and for any other tasks Giffard required.

The contract, drawn up by notary Mathurin Roussel in Mortagne-au-Perche, detailed the terms of their settlement. Giffard covered the cost of passage, along with three years’ worth of food, lodging, and basic necessities for Zacharie, Jean, and their two eldest sons. After two years, they were to send for the rest of their families—though this clause seemingly changed, as both men sailed with their entire families later that spring. In addition, Giffard granted each of them 1,000 arpents of land. Zacharie’s concession was known as La Clousterie (also referred to as La Clouterie or La Cloutièrerie), while Guyon’s land was named du Buisson. Both men were also granted the right to hunt, fish, and trade with Indigenous peoples. However, the agreement required Zacharie to swear fealty to Giffard—a clause that would later become a source of conflict.

The Percheron Emigration: From France to Canada

The Perche region played a key role in the settlement of New France, providing a steady stream of colonists willing to take on the challenges of life across the Atlantic. Many early settlers from this region embarked from the bustling port of La Rochelle, answering the call of men like Robert Giffard and the Juchereau brothers, Jean and Noël, who had been granted extensive land holdings in Canada. Their success depended on skilled workers who could clear land, build homes, and establish farms. The Compagnie des Cent-Associés helped finance the migration, bringing over families like the Cloutiers, Guyons, and Langlois. Today, the Museum of French Emigration to Canada in Tourouvre-au-Perche commemorates their journey.

Zacharie was among the settlers recruited to carve out new lives along the Beauport River. Before the arrival of Giffard’s recruits, the colony of New France numbered less than 100. Attracting more settlers was crucial to the survival of the remote French outpost.

The journey to the port of Dieppe was an adventure in itself. With over 200 kilometres to travel from Mortagne-au-Perche, the families likely packed their belongings into horse-drawn carts—furniture, household goods, tools, and the few personal items they could carry. In 1634, a group of 43 men, women, and children from Perche set off together, boarding four ships bound for New France.

17th-Century Québec, engraving by Alain Manesson Mallet (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Arrival in Québec

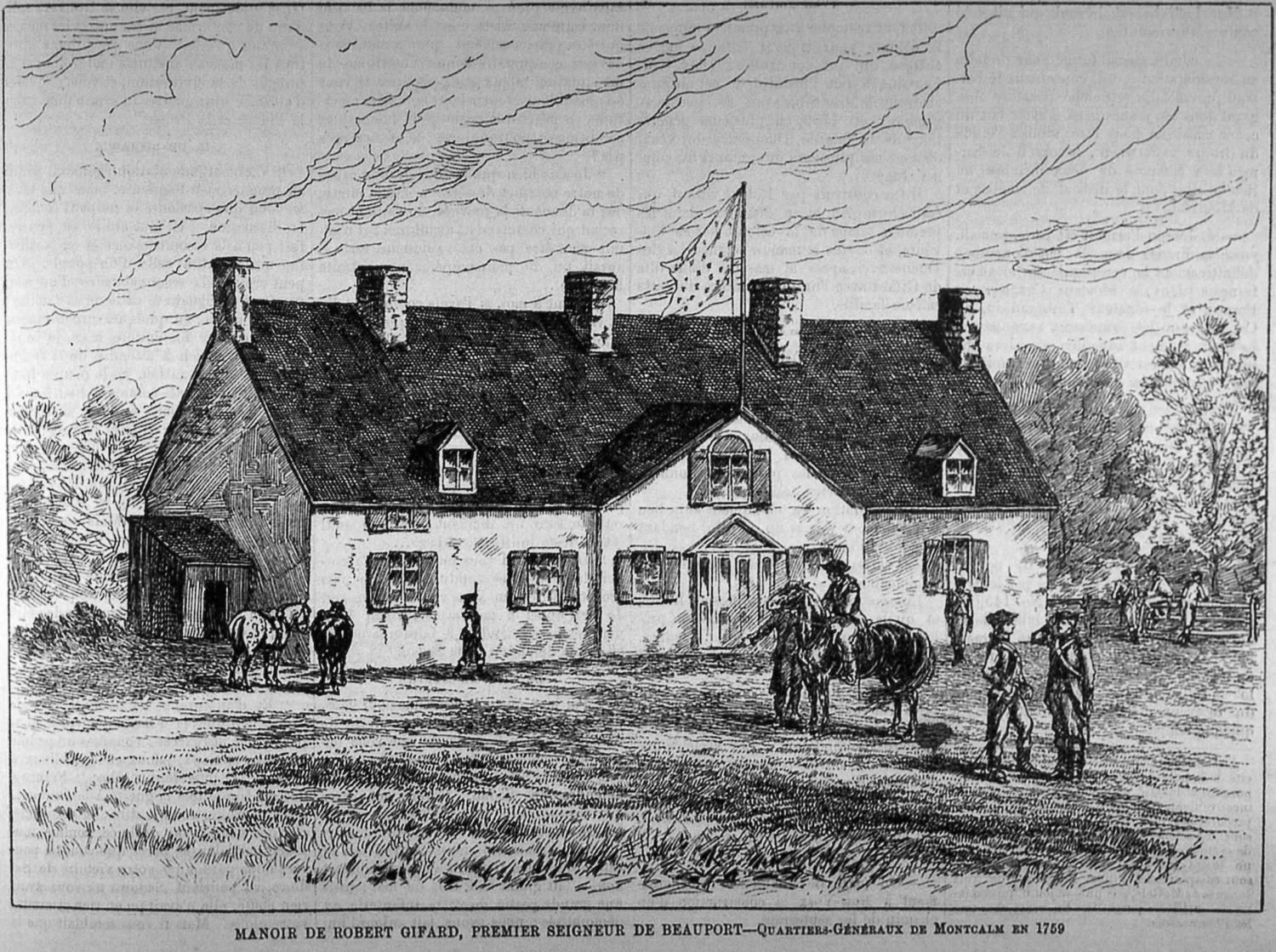

After more than a month at sea, Zacharie Cloutier, Jean Guyon, and their families arrived in Québec, likely on June 4, 1634. They disembarked alongside Robert Giffard and fellow settlers, including Gaspard Boucher and his family. Samuel de Champlain, eager to strengthen the colony, personally welcomed the new arrivals. Their first stop was the chapel of Notre-Dame de Recouvrance, where they gathered to give thanks for their safe passage. The newcomers were temporarily housed with Québec’s few established families, but there was little time to settle in. Within weeks, they were hard at work on Giffard’s seigneurie in Beauport, clearing land and constructing homes for the growing settlement. Zacharie and Jean were soon entrusted with an important task—the construction of Giffard’s manor near the Notre-Dame River.

Manor of Robert Giffard, drawing appearing in L’Opinion publique in 1881 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Château St-Louis, drawing appearing in L’Opinion publique in 1881 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Settling in Beauport

After fulfilling their contract obligations, Zacharie Cloutier and Jean Guyon officially took possession of their lands in Beauport on February 3, 1637.

1637 land possession acknowledgement (FamilySearch)

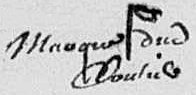

For several years, Zacharie and Jean lived and worked on their properties, as evidenced by numerous notarial documents. Although Zacharie was illiterate and unable to sign his name, he insisted on formalizing all agreements. Instead of a signature, he used a distinctive mark—an image resembling an axe—symbolizing his trade as a carpenter. His mark appears on several contracts, including the July 27, 1636, marriage contract of his 10-year-old daughter, Anne, to Robert Drouin, the first marriage contract signed in Canada. While early marriages were common in New France, Anne’s engagement at such a young age was remarkable even by contemporary standards. The contract stipulated that she and her future husband would live with her parents for three years. The marriage ceremony took place on July 12, 1637, when Anne was 11.

The marks of Martin Grouvel (left) and Zacharie Cloutier (right) on the 1636 marriage contract

The mark of Zacharie Cloutier on a 1650 land lease

Map of the seigneurie of Beauport prior to 1634, modelled after an original drawing by Samuel de Champlain (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Copy of a 1641 map showing the land between Québec and Cap Tourmente, by Jean Bourdon (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Building for the Colony

Initially, the Cloutier and Guyon families shared a home in Beauport. In time, Zacharie built his own residence on La Clousterie. His carpentry skills were in high demand, and he played a role in constructing several key structures in the colony. Among them were the Château St-Louis, the official residence of the Governor of New France, a Jesuit presbytery, a redoubt with a battery on Québec’s lower town quays, and numerous homes for fellow settlers.

On July 23, 1641, Zacharie Cloutier, identified as a “master carpenter residing in Beauport,” was hired by the Révérendes Mères Hospitalières de la Nouvelle-France to complete the wooden roof of their building, which was already under construction. The contract specified that the roof would have two folded ends, supported by three beams, and include three layers of joists matching the thickness of those used in the Jesuit building in Québec, “where the chapel is”. The beams were to be made of high-quality wood, matching those already in place. Additional structural elements included rafters, four chimney mantels, and sixteen double window frames similar to those in the nuns’ building in Sillery. A dormer window was also to be added. The chimney mantels and window frames were to be made of oak.

To assist with construction, the nuns agreed to provide two men to help transport wood to the site, a rowboat for moving materials by water, and three additional labourers to assist in raising the framework. Zacharie was to be paid 600 livres, half of which was payable in store provisions. The contract was signed by the Mother Superior before notary Piraube at the nuns’ hospital in Sillery.

1646 request by Robert Giffard to Charles Huault de Montmagny, Governor of New France, for permission to seize the lands of Jean Guyon and Zacharie Cloutier for lack of faith and homage, and permission granted by the Governor (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Conflict with Giffard

In 1646, a curious and rather inexplicable dispute arose between Giffard and his former recruits, Zacharie Cloutier and Jean Guyon. Years after their arrival in New France, Giffard attempted to enforce his right to demand foy et hommage—a formal act of fealty in which landholders swore loyalty to their seigneur. The ritual required Zacharie and Jean to visit Giffard’s manor, dressed in their finest clothing, kneel before him, and repeat three times, “I pledge to you faith and homage.”

Zacharie refused. He considered Giffard an equal, not a superior, and saw the ceremony as a humiliation. Jean followed his lead. Giffard also claimed the men owed him payment for cens et rentes (annual dues owed to the seigneur), which they also refused. Seeking enforcement, Giffard appealed to the governor, who ruled in his favour. Jean, unwilling to prolong the conflict, ultimately submitted and paid the dues. Zacharie, however, remained defiant, refusing to kneel but eventually paying after a court order compelled him to do so.

This dispute marked the beginning of years of legal battles between Giffard and his former recruits. He repeatedly took them to court, often over minor grievances. In 1659, one complaint accused them of allowing their farm animals to trespass on his land—despite Giffard permitting other settlers’ livestock to roam freely. Historians have yet to determine the exact cause of Giffard’s persistent legal actions against Zacharie and Jean, but the conflict remained unresolved for years.

Expanding His Holdings

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Feb 2025)

In the 1650s, Zacharie Cloutier continued working as a carpenter while also managing his landholdings through leases and new acquisitions.

On April 4, 1650, he agreed to build the frame of a house for master armorer Mathieu Huboux dit Deslongchamps. The contract, notarized by Guillaume Audouart, specified that the house would measure 25 feet long by 18 feet wide and be located in Québec at “the bottom of La Montée de Lhospital.” In exchange for his work, Zacharie was to receive 450 livres. As part of the payment, Huboux also promised to repair four weapons—three rifles and a pistol—and provide a mounted cannon measuring four and a half feet in length.

Later that year, on July 23, 1650, Zacharie leased a plot of land near rivière aux Chiens to Michel Blanot for one year. The land, measuring one arpent and twelve and a half perches, was already seeded with wheat. In return, Blanot agreed to deliver a poinçon of wheat after the harvest and to seed the land again for the following year. [The poinçon was an old measure of capacity for liquids and solids, estimated to be about 40 Canadian gallons.]

On October 3, 1651, Zacharie received a land concession in Québec from the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France. The act, penned by notary Audouart, granted him a lot measuring 40 feet long by 24 feet wide “below the Sault aux Matelots,” with the condition that he construct a building on the site within a year.

Later Years in Québec

By the end of 1659, Zacharie and Sainte had an empty nest. Their youngest son, Charles, had left home, and while Zacharie still took on carpentry projects, he began stepping back from the physical demands of farming. Instead, he entrusted much of the farm labour to his son-in-law, Jean Mignault dit Châtillon.

On June 30, 1665, Zacharie and his sons—Zacharie Jr., Jean, and Charles—sold a timber-framed house in Québec’s lower town to Jacques Cailleteau, sieur de Champfleury, for 600 livres. The house, which measured 40 feet long by 20 feet wide, backed onto the quay of the St. Lawrence River. Zacharie had originally received the concession on August 7, 1658, from Governor d’Argenson. Only Zacharie Jr. was able to sign his name on the deed of sale. [The original concession could not be located.]

Move to Château-Richer

The first census of New France, conducted in 1666, recorded Zacharie and Sainte living on the côte de Beaupré in Château-Richer, about 20 kilometres northeast of Beauport. Zacharie, listed as an habitant, was recorded as 76 years old, while Sainte was listed as 70. In the 1667 census, they were still living in Château-Richer. At the time, they owned two farm animals but had no cleared land to their name.

1666 census of New France for the Cloutier household (Library and Archives Canada)

1667 census of New France for the Cloutier household (Library and Archives Canada)

The exact date of Zacharie and Sainte’s move to Château-Richer is unknown, but it was likely before 1663, as all three of their sons had already settled in the area by then.

Arranging Their Legacy

On January 19, 1668, Zacharie and Sainte gathered their children and key family members at their home in Beauport to formalize an inheritance agreement before notary Michel Fillion. Present were their sons Zacharie, Jean, and Charles, as well as their daughter Louise, represented by her husband Jean Mignault dit Châtillon. Also in attendance were Pierre Maheu and his wife Jeanne Drouin, and Romain Trépagny and his wife Geneviève Drouin—both Jeanne and Geneviève were Zacharie and Sainte’s granddaughters.

Though both Zacharie and Sainte were described as being “in good health,” they acknowledged that “nothing is more certain than death” and sought to “prevent disputes arising after their death between their heirs.” Their eldest son, Zacharie Jr., received the rights to the fief of La Clousterie in Beauport, including the house, barn, stable, oven, and other buildings on the land. The rest of their movable and immovable property was to be divided among all the heirs after their deaths. However, Zacharie Jr. agreed not to claim an equal share of these remaining assets. Until their passing, Zacharie and Sainte retained full use of their property, and in return, their children committed to provide for them.

A year later, on May 12, 1669, Zacharie and Sainte went before notary Claude Auber to formalize a donation to their eldest son, Zacharie Jr., and his wife, Madeleine Émard (or Esmard), who lived on a large farm in Château-Richer. In this deed, they transferred to him “their movable property, debts, land, annuities, income and possessions whatsoever,” acknowledging that he “has always helped them and given them kindness, service and helpfulness.” In return, Zacharie and Madeleine promised to provide them with “food and drink as well as fire and light, clothes, shoes, sheets, linen and generally all their necessities.” They also agreed to ensure they were “treated, medicated and cared for” until their deaths.

Final Sale of La Clousterie

On December 20, 1670, Zacharie and Sainte sold La Clousterie to Nicolas Dupont, a member of the Sovereign Council, for 4,500 livres.

Deaths of Zacharie and Sainte

Zacharie Cloutier died at around 87 years old on September 17, 1677, and was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Château-Richer. Sainte Dupont passed away on July 13, 1680, at approximately 84 years old, though her burial record states she was 97. She was buried in the same cemetery the next day.

1677 burial of Zacharie Cloutier (Généalogie Québec) [copy; original record no longer exists]

1680 burial of Sainte Dupont (Généalogie Québec)

A Lasting Legacy

Zacharie and Sainte are remembered as the most prolific immigrants to settle in Canada. Zacharie is considered the sole ancestor of all Cloutiers in New France and appears in the lineage of many well-known figures, including Céline Dion, Jack Kerouac, Madonna, Justin Trudeau, and Camilla Parker Bowles. His name even lives on in a sheep’s milk cheese, Zacharie Cloutier, produced by Fromagerie Nouvelle France.

Several locations in Québec commemorate Zacharie Cloutier:

Parc Zacharie-Cloutier in Beauport, situated on land that was once part of his fief. A plaque in his honour, created by the Association des Cloutier d’Amérique, is located there.

Pont Zacharie-Cloutier, a bridge spanning the Sault-à-la-Puce River in Château-Richer, near his ancestral land.

Rue Zacharie-Cloutier, a street in Beauport named in his honour in 2006.

An interesting fact: although the Cloutier (or Cloustier) name was relatively common in 16th- and 17th-century Perche, it has all but disappeared from the Orne department in France.

Today, Château-Richer is considered the heart of the Cloutier family in North America, with at least ten generations having lived there since 1641.

“Château-Richer, Québec,” circa 1939 painting by Léonce Cuvelier (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Aerial view of Château-Richer, circa 1927 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Processional chapel in Château-Richer, circa 1930 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Church at Château-Richer (© perche-quebec.com - Jean-François Loiseau; photo used with permission)

Commemorative plaque displayed in Mortagne-au-Perche (© Association Perche-Canada; photo used with permission)

Commemorative plaque displayed in Mortagne-au-Perche (© Association Perche-Canada; photo used with permission)

Inherited Medical Condition?

Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD) is a genetic disorder that causes progressive muscle weakness, primarily affecting the upper eyelids and throat. Symptoms typically appear in adulthood, usually between the ages of 40 and 60, and may include eyelid drooping (ptosis), difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and weakness in the arms and legs. The condition is particularly prevalent among French Canadians, where it is estimated to affect 1 in 1,000 people.

Genetic research has traced the affected gene in French-Canadian OPMD patients back to a common ancestral couple: Zacharie Cloutier and Sainte Dupont. Further studies suggest that the mutation was passed through their son, Zacharie Cloutier Jr., and his wife, Madeleine Émard (or Esmard).

Treatment varies depending on the symptoms and may include surgical options. If you experience any of these symptoms and have the Cloutier-Émard couple in your family tree, you may wish to discuss this with your doctor.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"REGISTRE PAROISSIAL : Mortagne-au-Perche (paroisse Saint-Jean et Saint-Malo), 1600-1712," digital images, Direction des archives et du patrimoine culturel de l'Orne (https://gaia.orne.fr/mdr/index.php/docnumViewer/calculHierarchieDocNum/378791/1057:371440:372097:378791/1440/3440 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), marriage of Michel Lermusier and Sainte Dupont, 26 Feb 1612, image 195 of 957.

Ibid. (https://gaia.orne.fr/mdr/index.php/docnumViewer/calculHierarchieDocNum/378791/1057:371440:372097:378791/1440/3440 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), marriage of Zacharie Cloustier and Sainte Dupont, 18 Jul 1616, image 198 of 957.

Madame Pierre Montagne [Françoise Lamarche], Tourouvre et les Juchereau : Un chapitre de l’émigration percheronne au Canada (Québec, Société Canadienne de Généalogie, 1965).

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/30534 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), burial of Zacharie Cloustier, 18 Sep 1677, Château-Richer (La-Visitation-de-Notre-Dame) ; citing original data: Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/30545 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), burial of Sainte Dupont, 15 Jul 1680, Château-Richer (La-Visitation-de-Notre-Dame).

"Les Pionniers," Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (https://www.prdh-igd.com/fr/les-pionniers : accessed 17 Feb 2025).

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/87760 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), dictionary entry for Zacharie CLOUTIER and Sainte DUPONT, union 87760.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=241403 : accessed 26 Feb 2025), entry for Sainte DUPONT (person #241403), updated on 8 Jun 2023.

Raoul Clouthier, Les CLOUTIER de Mortagne-au-Perche en France et leurs descendants au Canada, 1973, digitized in 2002 by Pierre Cloutier (https://dubuc-landry.ca/autres/Cloutier%20Zacharie%20-%20Xainte%20Dupont-TNG.pdf).

"Actes de notaire, 1643-1648 / Guillaume Tronquet," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-QDNJ?cat=1176008&i=665&lang=en : accessed 26 Feb 2025), land possession by Zacharie Cloutier and Jean Guion, 3 Feb 1637, image 666 of 2,056 ; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1626-1645 / Martial Piraube," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-Q8GW?cat=1176010&i=1127&lang=en : accessed 26 Feb 2025), carpentry contract between Zacharie Cloutier and the Reverendes mères religieuses Hospitalières de la Nouvelle France, 23 Jul 1641, images 1,128-1,129 of 2,056 ; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1634, 1649-1663 / Guillaume Audouart," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-3292?cat=1171569&i=143&lang=en : accessed 17 Feb 2025), contract for the carpentry of a house between Zacharie Cloutier and Mathieu Huboust dit Deslonchamps, 4 Apr 1650, images 144-147 of 2,642 ; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-3J7J?cat=1171569&i=235&lang=en : accessed 17 Feb 2025), land lease agreement by Zacharie Cloutier to Michel Blanot, 23 Jul 1650, images 236-237 of 2,642.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-3LQ9?cat=1171569&i=474&lang=en : accessed 17 Feb 2025), site concession to Zacharie Cloutier by the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, 3 Oct 1651, images 475-477 of 2,642.

"Actes de notaire, 1660-1688 / Michel Fillion," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-QHCJ?cat=1176077&i=1612&lang=en : accessed 26 Feb 2025), sale of a house by Zacharie Cloustier, Zacharie Cloustier, Jean Cloustier and Charles Cloustier, to

Jacques Cailteau de Champfleury, 30 Jun 1665, image 1,613 of 2,056 ; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVN-QHWL?cat=1176077&i=1700&lang=en : accessed 26 Feb 2025), agreement between Zacharie Cloustier and Sainte Dupont, Zacharie Cloustier, Jean Cloustier, Charles Cloustier, Jean Mignault de Chastillon and Louise Cloustier, Pierre Maheu dit Deshazars and Jeanne Drouin, and Romain Trespagny and Geneviève Drouin, 19 Jan 1668, images 1,701-1,702 of 2,056.

"Actes de notaire, 1652-1692 / Claude Auber," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53L2-614M?cat=1175225&i=915&lang=en : accessed 26 Feb 2025), donation by Zacharie Clouttier and Sainte Dupont to their son Zacharie Cloustier and his wife Madeleine Esmard, 12 May 1669, images 916-917 of 1,368 ; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Parchemin, notarial database of ancient Québec (1626-1801), Société de recherche historique Archiv-Histo (https://archiv-histo.com : accessed 26 Feb 2025), "Vente de la terre, fief et seigneurie de la Clousterie; par Zacharie Cloutier et Sainte Dupont, son épouse, de Chasteau Richer, à Nicolas Dupont de Neufville, écuyer et conseiller au Conseil souverain," notary G. Rageot, 20 Dec 1670.

"Collection Centre d'archives de Québec - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/367027 : accessed 26 Feb 2025), "Contrat de mariage entre Robert Drouin et Anne Cloutier," 27 Jul 1636, reference P1000,S3,D603, Id 367027.

"Fonds Gouverneurs, régime français - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/371955 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), "Requête par Robert Giffard, seigneur de Beauport, à Charles Huault de Montmagny, gouverneur de la Nouvelle-France, lui demandant permission de procéder à la saisie des terres de Jean Guyon (Guion) et Zacharie Cloutier pour manque de foi et hommage, et permission accordée par ledit gouverneur," 2 Jul 1646, reference R1,P4, Id 371955.

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 17 Feb 2025), entry for Zacarie Cloutier, page 58 (of PDF), 1666, côte de Beaupré, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 17 Feb 2025), entry for Zacarie Cloustier, page 142 (of PDF), 1667, côte de Beaupré, Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Françoise Barthe, "La terre de Zacharie Cloutier," La Clouterie, Sep 2002, volume XIX, number 3, page 15.

Ville de Québec, “Toponymie : Fiche Zacharie-Cloutier” (https://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/citoyens/patrimoine/toponymie/fiche.aspx?idFiche=4882).

Munitiz et al., “Diagnosis and treatment of oculopharyngeal dystrophy: A report of three cases from the same family,” Diseases of the Esophagus (2003), 16, 102-106, digitized by ResearchGate (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10694239_Diagnosis_and_treatment_of_oculopharyngeal_dystrophy_A_report_of_three_cases_from_the_same_family : accessed 26 Feb 2025).