The 1847 Typhus Epidemic in Canada

2022 marks the 175th anniversary of Irish mass immigration to Canada. Fleeing the Great Famine, many Irish families boarded ships for the U.S. and Canada to start a new life. "Black '47", however, was a devastating year for the Irish, both in their home country and for those who travelled to North America. The dirty, overcrowded ships had an unwanted and deadly passenger: typhus.

2022 marks the 175th anniversary of Irish mass immigration to Canada. Fleeing the Great Famine, many Irish families boarded ships for the U.S. and Canada to start a new life. "Black '47", however, was a devastating year for the Irish, both in their home country and for those who travelled to North America. The dirty, overcrowded ships had an unwanted and deadly passenger: typhus.

Typhus in a (Medical) Nutshell

WWII poster, National Archives (USA).

What is Typhus? How is it transmitted?

Epidemic typhus is a disease caused by the bacteria Rickettsia prowazekii. It is transmitted to people through infected body lice. Other types of typhus include sylvatic typhus (spread by flying squirrels), scrub typhus (spread by chiggers) and murine typhus (spread by fleas on rats). For the purposes of this article, "typhus" refers to Epidemic typhus.

What are the Symptoms of Typhus?

Within two weeks of being exposed to infected lice, a person can experience fever, chills, headache, rapid breathing, body aches, dark red spots on the skin, cough, nausea, vomiting and confusion. Once infected, an untreated victim can die within three or four days.

How is it Diagnosed and Treated?

Today, the presence of epidemic typhus is detected through diagnostic tests (blood tests or biopsies, for example) and treated with the antibiotic doxycycline. An infected person treated early normally recovers quickly. Unfortunately for our ancestors, this treatment was not available in 1847.

How is Typhus Prevented?

Typhus is best prevented by avoiding areas with poor sanitation and overcrowding, which would allow lice to spread easily from person to person. A vaccine for typhus was developed in the early 20th century. It was only successful in reducing the disease’s mortality, however, not in preventing infection.

Does it Still Exist?

Today, typhus is considered a rare disease. It is still endemic in countries with unhygienic overcrowding.

The Great Famine

From 1845 to 1851, Ireland experienced an extraordinary period of hardship dubbed the "Great Famine", the "Potato Famine" or the "Great Hunger." Potato blight caused crops to fail during successive years, leading to mass starvation and malnutrition. Over 1 million people are believed to have died from starvation or disease, while another million left Ireland for North America or Great Britain. Within a decade, Ireland's population went from 8.5 million to just over 5 million. Learn more about the Great Famine here.

“An Irish Peasant Family Discovering the Blight of their Store,” 1847 painting by Daniel MacDonald.

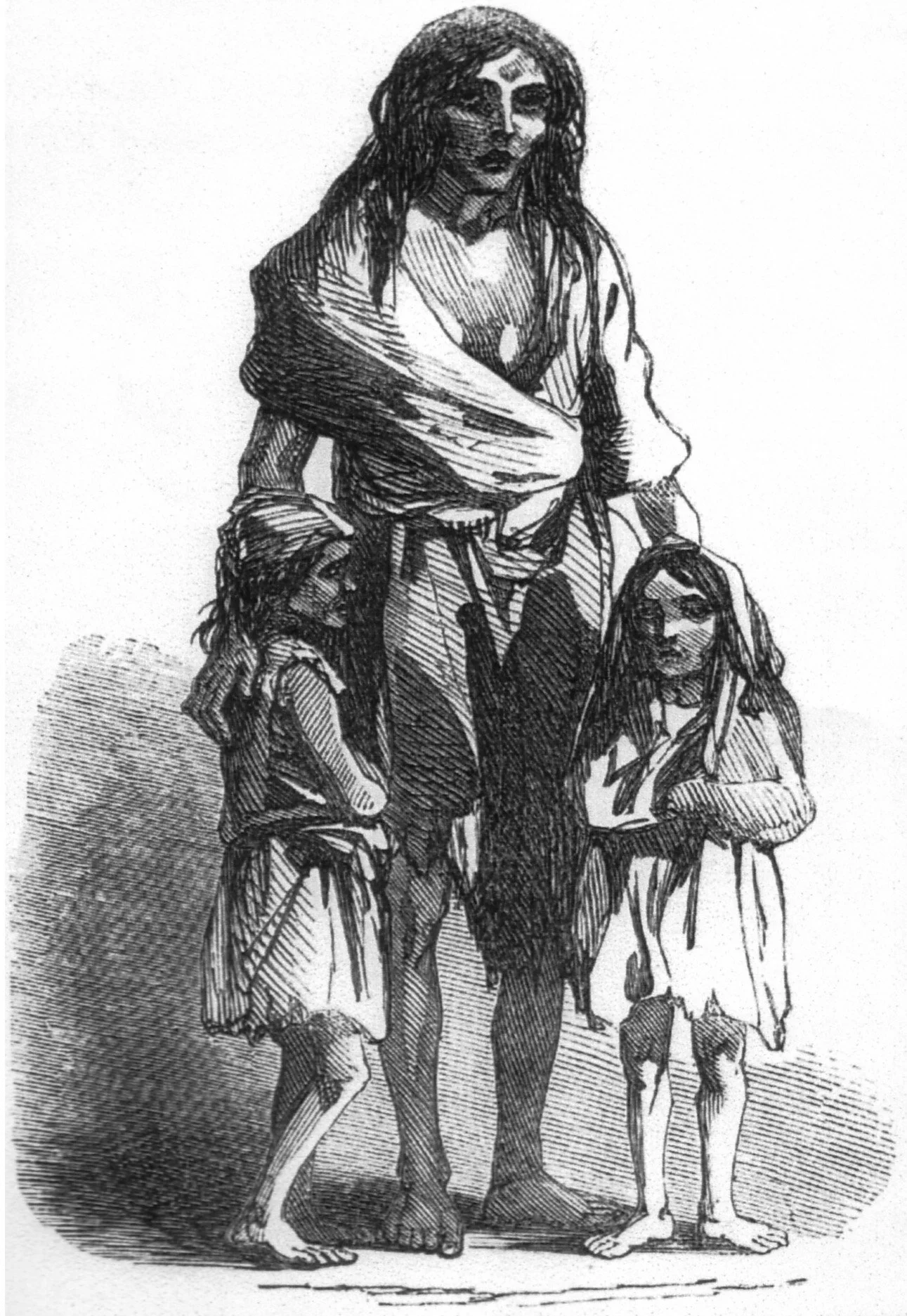

A depiction of Bridget O'Donnell and her two children during the famine appearing in the Illustrated London News on December 22, 1849.

"The Famine in Ireland, Funeral at Skibbereen”, drawing by Frederick James Smyth appearing in The Illustrated London News on January 30, 1847.

1847 was a particularly deadly year in Ireland. Not only was a large portion of the population affected by starvation, epidemics of typhus, dysentery and smallpox soon spread throughout the country.. On April 17 the Roscommon Journal reported: “Deaths by famine are now so frequent that whole families who retire to rest at night are corpses in the morning and frequently are left unburied for days for want of coffins.”

The Freeman’s Journal, January 12, 1847

The Freeman’s Journal, April 13, 1847

Mass Emigration to North America

Many Irish families had to make a difficult decision: stay in Ireland and struggle to survive or take their chances and sail to North America. Though the U.S. was seen as a more desirable destination, many chose Canada because tickets were cheaper (about £1 to 3 less). Once their passage was paid, the travellers soon discovered that the ships were ill-equipped to transport people for a long period of time. They were rat-infested, filthy and overcrowded, earning them the nickname "coffin ships." Many passengers came aboard with typhus, or "ship fever", and spread it to others during their six- to eight-week passage .

A Dangerous Voyage

During 1847 alone, over 100,000 Irish passengers travelled from the British Isles to the British North American Colonies. 90,000 sailed towards Quebec, 17,000 to New Brunswick, and the remainder to other Atlantic ports. Between 5,000 and 8,000 travellers died at sea and were thrown overboard. At least three ships sank en route to Canada: the Exmouth of Newcastle (241 passengers), the Carricks of Whitehaven (173 passengers) and the Miracle from Liverpool (400 passengers).

The Freeman’s Journal, June 5, 1847

Illustration from Preface to the First Edition of An Illustrated History of Ireland from AD 400 to 1800, by Mary Frances Cusack, Illustrated by Henry Doyle , published in 1868.

The Freeman’s Journal, August 12, 1847

Typhus Arrives in Canada

Typhus had been present in Canada previously, but there was only one typhus epidemic to ever affect the country: that of 1847 in Québec, Ontario and New Brunswick, brought about by the Irish immigration. At that time, there were many names for typhus: jail fever, camp fever, hospital fever, ship fever, road fever and Irish fever. Some newspapers even called it "Emigrant Typhus."

"View of the Quarantine Station of Grosse Île," 1850 painting by Henri Delattre, Library and Archives Canada.

Grosse-Île was the first point of entry for most travellers who managed to survive the crossing. Located just upstream from Quebec City in the St-Lawrence, it was initially set up as a quarantine station to prevent the spread of cholera in 1832. Authorities used it again in 1847, hoping to stop "ship fever" from landing on Canadian soil. By May 20th, about 30 ships were anchored at Grosse-Île. The staff was quickly overwhelmed, having to examine over 90,000 passengers in one year, and burying at least 5,000 dead. Some died from dysentery but most succumbed to typhus. Mass graves were dug, and men were paid $4 per day to collect the bodies from the ship holds with hooks and bring them to the graves.

Photos of Grosse-Île

Temporary "sheds" were erected, and new buildings were rapidly constructed on the island to house the many patients, but it still wasn't enough. Many passengers had to remain aboard their disease-infested ships because Grosse-Île was too crowded. Things weren't necessarily better on the island. The so-called sheds were never meant to house people—they had no ventilation nor privies, resulting in the rapid spread of disease. Over 9,000 deaths were recorded at Grosse-Île during the entire epidemic. Inspections were carried out hastily, allowing many immigrants with latent fever to pass as healthy and leave the island (it could take 10 to 12 days for an infected person to show symptoms). Some ships were diverted to Montreal, where fever sheds were set up in Pointe-Saint-Charles and Griffintown. Those who died there were buried in mass graves next to the sheds, often three coffins deep.

Portion of "Map of the city of Montreal showing the Victoria bridge the mountain & proposed boulevard, and the different dock projects," 1859 map by Frederick Boxer and John Lovell, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Emigrant sheds, renovated to provide accommodations for contractors working on the Victoria Bridge. Photo by William Notman, circa 1858. McCord Museum.

A mass burial entry in the register of Grosse-Île, detailing the deaths of 3 persons aboard the Herald, 4 persons aboard the Elizabeth and 30 persons “from different hospitals,” June 25, 1847, FamilySearch.

A mass grave in Pointe-Saint-Charles was discovered in 1859 during the construction of the Victoria Bridge. The workers who discovered the site, most of them Irish, paid to have a monument erected to remember the deceased. Called "The Black Rock", its inscription reads: "To Preserve from Desecration the Remains of 6000 Immigrants Who died of Ship Fever A.D. 1847-48. This Stone is erected by the Workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts Employed in the Construction of the Victoria Bridge A.D. 1859." It is considered the oldest famine memorial in the world.

“Victoria Bridge Monument, Montreal,” 19th-century engraving by John Henry Walker, McCord Museum.

“Laying the Monumental stone, marking the graves of 6000 immigrants, Victoria Bridge, Montreal, QC, 1859", photo by William Notman, McCord Museum.

Fighting Typhus in Canadian Cities

The Perry County Democrat (Bloomfield, PA), November 25, 1847

Despite these preventative efforts, typhus-infected passengers did come ashore and triggered an epidemic in Canada's cities. Over 1,000 typhus deaths were recorded in Quebec City, between 3,500 and 6,000 in Montreal and over 4,000 in various cities in Ontario (then called Canada West). The mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, died of the disease on November 12, 1847. The Montreal Gazette reported that "He was daily at the Sheds, sometimes for hours together, and has often been seen at the bedside of some miserable and dying emigrant, administering with his own hands that relief which he so much needed. In this discharge of a most painful and onerous office, Mr. Mills contracted the disease which has terminated an honored and a useful life".

The Montreal Gazette, August 25, 1847

Religion played a significant role in the epidemic, as religious orders were generally the ones called upon to care for the sick. In Montreal, the Grey Nuns were the first to visit the sheds in May of 1847, but they soon lost many of their own to the illness. The Sisters of Providence came to assist in June, then took over from the Grey Nuns entirely in July as they left to recover from the disease. The nuns from the Hôtel-Dieu also lent a hand but left quickly in order to care for the priests who had contracted typhus. The Grey Nuns returned in September and remained until the closure of the sheds seven months later. At least 30 priests and nuns became infected with typhus. 21 of them later died of the disease.

"Le typhus," 1848 oil painting by Théophile Hamel in the Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours, Musée Marguerite-Bourgeoys.

The clergy's involvement during the typhus epidemic was not without controversy in Montreal. Many Irish Protestants converted to Catholicism at the urging of the clergy, or simply to get better treatment. Nuns also convinced young Protestant orphans to become Catholic. Several historians remarked that the "race" to conversion became more important than treatment. On the other hand, most doctors in Montreal were Protestant. Catholic nuns reported being shunned from caring for those in the Protestant sheds, or being denied the materials they needed.

Irish Orphans

Over 3,000 Irish children lost their parents in the province of Quebec (Canada East). In Montreal, many charitable organizations like the Grey Nuns cared for the children of Irish immigrants who died from typhus. The Sisters of Providence opened the Saint-Jérôme-Émilien hospice for Irish orphans. Priests pleaded with their parishioners to adopt the children. Many of those adopted were able to keep their Irish surnames, still prominent in Quebec today. Walsh, Lynch, Nelligan, McMahon, O'Brien and O'Gallagher are just a few examples. The majority of the orphans, however, were not adopted but placed into host families. They worked as farm hands or servants in exchange for room and board.

Heritage Minutes: Orphans, Historica Canada.

In New Brunswick

Many Irish immigrants came ashore in Saint-John, New Brunswick. In 1847, the city's population was only 30,000. A sudden influx of 16,000 arrivals in the summer and fall of that year was too much for the city to handle. A pest house and quarantine station were reopened on Partridge Island, just outside the main harbour. The island, now extremely crowded with immigrants, became a new breeding ground for typhus. Resentment against the Irish grew, as public funds from an already poor city were being diverted to help the immigrants. By the end of the year, over 2,000 people had died of typhus in New Brunswick, over half of them on Partridge Island and in Saint-John.

View of Partridge Island, Wikimedia Commons

In Canada West (Ontario)

The Ottawa Daily Citizen, June 19, 1847

About half of the total immigrants were Protestants from Northern Ireland. They, along with a sizeable Irish Catholic contingent, made their way west of Montreal, settling in Bytown (now Ottawa), Kingston and Toronto. During the summer of 1847, roughly 38,000 Irish refugees arrived in Toronto, a city of only 20,000. 863 died of typhus in the fever sheds on the grounds of the hospital at King and John streets. Many bodies were buried in St. Paul's cemetery in the city's Corktown neighbourhood. As in Montreal, many priests and nuns, both Catholic and Protestant, lost their lives while treating the victims of typhus and contracting the disease themselves.

In Bytown, the sudden influx of 3,000 Irish immigrants triggered a typhus outbreak. Sheds were quickly constructed and about 200 people died while in quarantine. In Kingston, sheds were also erected. Over 1,400 Irish immigrants died there.

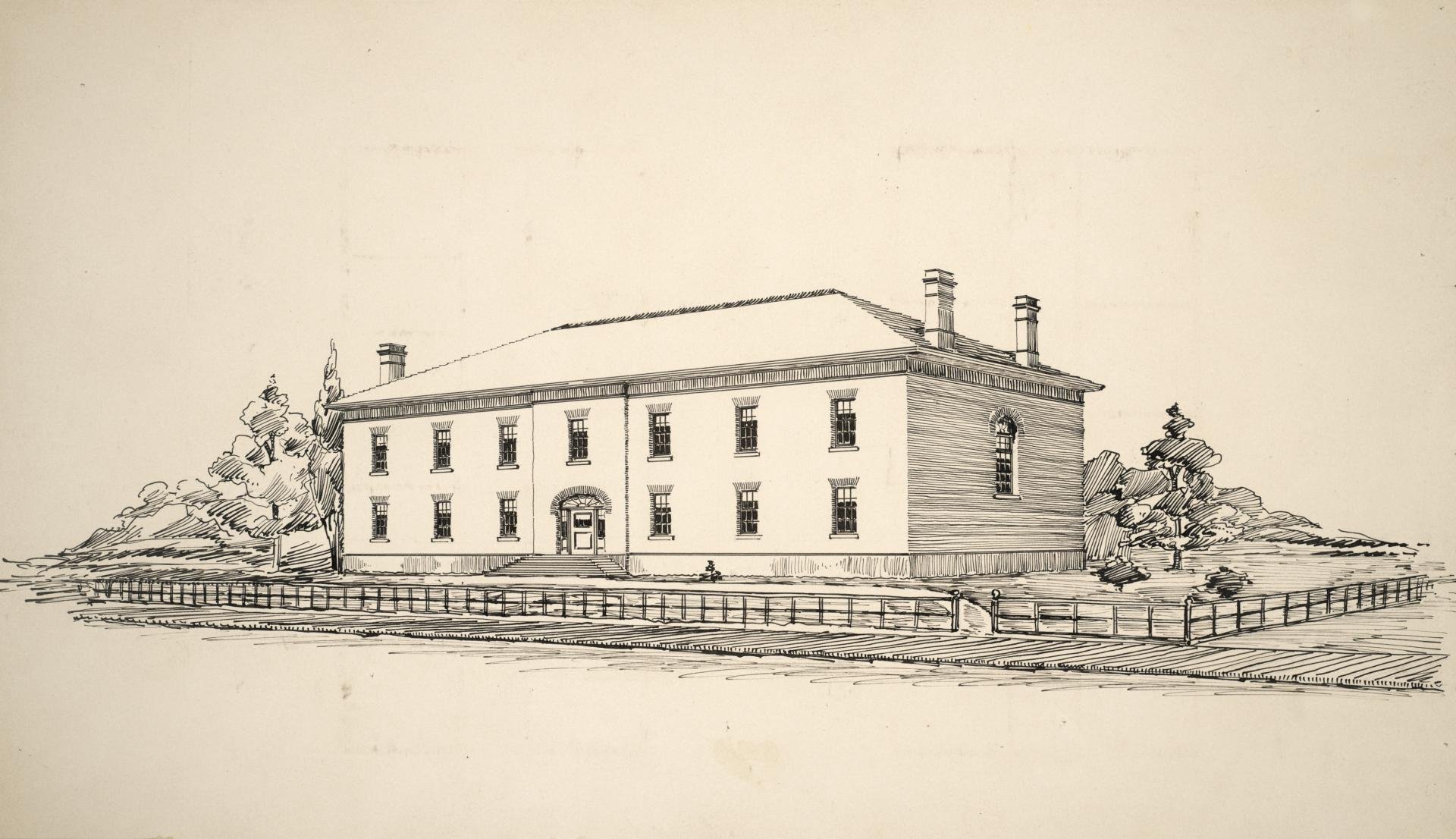

"Hospital, King Street West, northwest corner John St," circa 1858 drawing by Owen Staples, Toronto Public Library.

Blame and Discrimination

Irish immigrants were blamed for the typhus epidemic and faced intense discrimination in their new country. In 1847, A. B. Hawke, Chief Emigrant Agent for Canada West, said "More than three-fourths of the immigrants this year have been Irish, diseased in body, and belonging generally to the lower class of unskilled labourers. Very few of them are fit for farm servants." In Toronto, anti-Catholic sentiment of many Protestant residents made settling there incredibly difficult for the Irish. A column from the Globe read "“Irish beggars are to be met everywhere, and they are ignorant and vicious as they are poor. They are lazy, improvident and unthankful; they fill our poorhouses and our prisons.” Many Toronto businesses posted signs reading "No Irish Need Apply". Unable to find jobs, many Irish left the city, some headed for the U.S. while others went to Niagara and Hamilton.

The Montreal Gazette, March 15, 1848

Cures and Remedies

Newspaper articles of the time made it clear that typhus was associated with a lack of cleanliness, but the specific cause of the disease was yet unknown. Several preventative cures were suggested by the newspaper the Scottish Guardian:

Do not sit in the draught, it is dangerous.

Making up a warm or ill aired bed will produce disease.

Accustom your children not to be afraid of the cold water sponge. They will come to like it and apply it themselves.

Do all you can to avoid hanging your washings to dry in the rooms you live in. Nothing is more dangerous to health.

Never live on poor food that you may save money for drink. Simple directions for thrifty and good cooking will be sent to you. Strive to learn the best ways in the meantime from your neighbors who can cook well.

Lose no opportunity of walking and taking exercise in the open air.

And, as we've seen with other diseases during this time like cholera, alcohol was also blamed.

Remember that no drinker ever rises above the lowest poverty. Mark this, too, typhus finds out the drunkard and fastens on him.

The End of the Epidemic

As a result of the typhus epidemic, many boards of health were created throughout the Canadas. The public was encouraged to read their reports and comply with their recommendations, which focused on cleanliness. Though cases of typhus were still being reported, the epidemic was officially declared over in April of 1848. The official cause of typhus, and its method of transmission, would only be discovered in 1916. The Canadian typhus epidemic is believed to have caused 20,000 deaths in 1847.

The memorial cross at Grosse-Île, circa 1900, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Commemorative Monuments

Many memorials have been erected in memory of the Irish that came and those that perished, as well as the Canadian victims who died while trying to help. A Celtic cross was erected in Saint-John, New Brunswick. A provincial plaque was installed in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Kingston, Ontario. A statue was installed in Ireland Park in Toronto. In 2021, Grasett Park was also opened in Toronto, located where the fever sheds once stood. The park is named in honour of Dr. George Robert Grasett, the Medical Superintendent of the Toronto Hospital in 1847, who died of typhus. It "celebrates the response of the City of Toronto, particularly its physicians, nurses and other caregivers, to the influx of Irish migrants during the summer of 1847, many of whom arrived sickened and gravely afflicted from typhus, known then as ship fever".

Note: the figures reported for infections, deaths and orphaned children vary greatly depending on source used (see sources below). The most commonly cited numbers were used in this article.

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources & Further Reading:

Belley, Marie-Claude, "Un exemple de prise en charge de l'enfance dépendante au milieu du XIXe siècle : les orphelins irlandais à Québec en 1847 et 1848," thesis presented to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of Université Laval, Sep 2003.

Braithwaite, Max, "The Nightmare Story of the Irish Flight to Canada", Maclean's (https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1953/9/1/the-nightmare-story-of-the-irish-flight-to-canada), 1 Sep 1953.

Canada Ireland Foundation, "Grasett Park" (https://www.canadairelandfoundation.com/grasettpark/).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Epidemic Typhus" (https://www.cdc.gov/typhus/epidemic/index.html).

Charest, Maude, "Prosélytisme et conflits religieux lors de l’épidémie de typhus à Montréal en 1847," Cap-aux-Diamants, number 112, winter 2013.

Cummings, Don , and Serge Occhietti, "Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/la-grosse-ile). Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited June 06, 2018.

George, Ruggles, “When Typhus Raged in Canada,” The Public Health Journal 11, no. 12 (1920): 548–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41972635.

Landry, Martin, "L’épidémie du typhus de 1847," Histoire Canada (https://www.histoirecanada.ca/consulter/sciences-et-technologies/l-epidemie-du-typhus-de-1847), published online 27 May 2020.

Lemoine, Réjean, "Grosse-Île : cimetière des immigrants au XIXe siècle," Cap-aux-Diamants, 1(2), 9–12, digitized by Érudit (https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/6350ac).

McGowan, Dr. Mark, InsightOut: The Typhus Epidemic of 1847 (video), University of Toronto (https://stmikes.utoronto.ca/news/insightout-the-typhus-epidemic-of-1847).

Nelder, M.P., Russell, C.B., Johnson, S. et al. Assessing human exposure to spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae in Ontario, Canada (2013–2018): a retrospective, cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 20, 523 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05244-8.

Scott, Marian, "Montreal, refugees and the Irish famine of 1847," The Montreal Gazette (https://montrealgazette.com/feature/montreal-refugees-and-the-irish-famine-of-1847), 12 Aug 2017.

Tucker, Gilbert, “The Famine Immigration to Canada, 1847,” The American Historical Review 36, no. 3 (1931): 533–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1837913.