The History of l'Île-d'Orléans

Most French Canadians can trace at least one, if not dozens, of ancestors who called l'Île-d'Orléans home centuries ago. Glimpses of traditional Canadian life still remain on the island today. It's not surprising that l'Île-d'Orléans has been called the "Cradle of French America".

Cliquez ici pour la version française

The History of Île-d'Orléans

Saint-Pierre-de-l'Île-d'Orléans. 2015 photo by giggel.

Poster child for Québec tourism, Île-d'Orléans evokes images of days long gone: quaint villages, old stone houses with thatched roofs, rolling fields and orchards. Most French Canadians can trace at least one, if not dozens, of ancestors who called Île-d'Orléans home centuries ago. Life here certainly has changed, but glimpses of traditional Canadian life still remain. It's not surprising that Île-d'Orléans has been called the "Cradle of French America."

“Entrance to the St. Lawrence River, and Québec City in Canada” (map attributed to cartographer Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, created between 1670 and 1693, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

An Island of Many Names

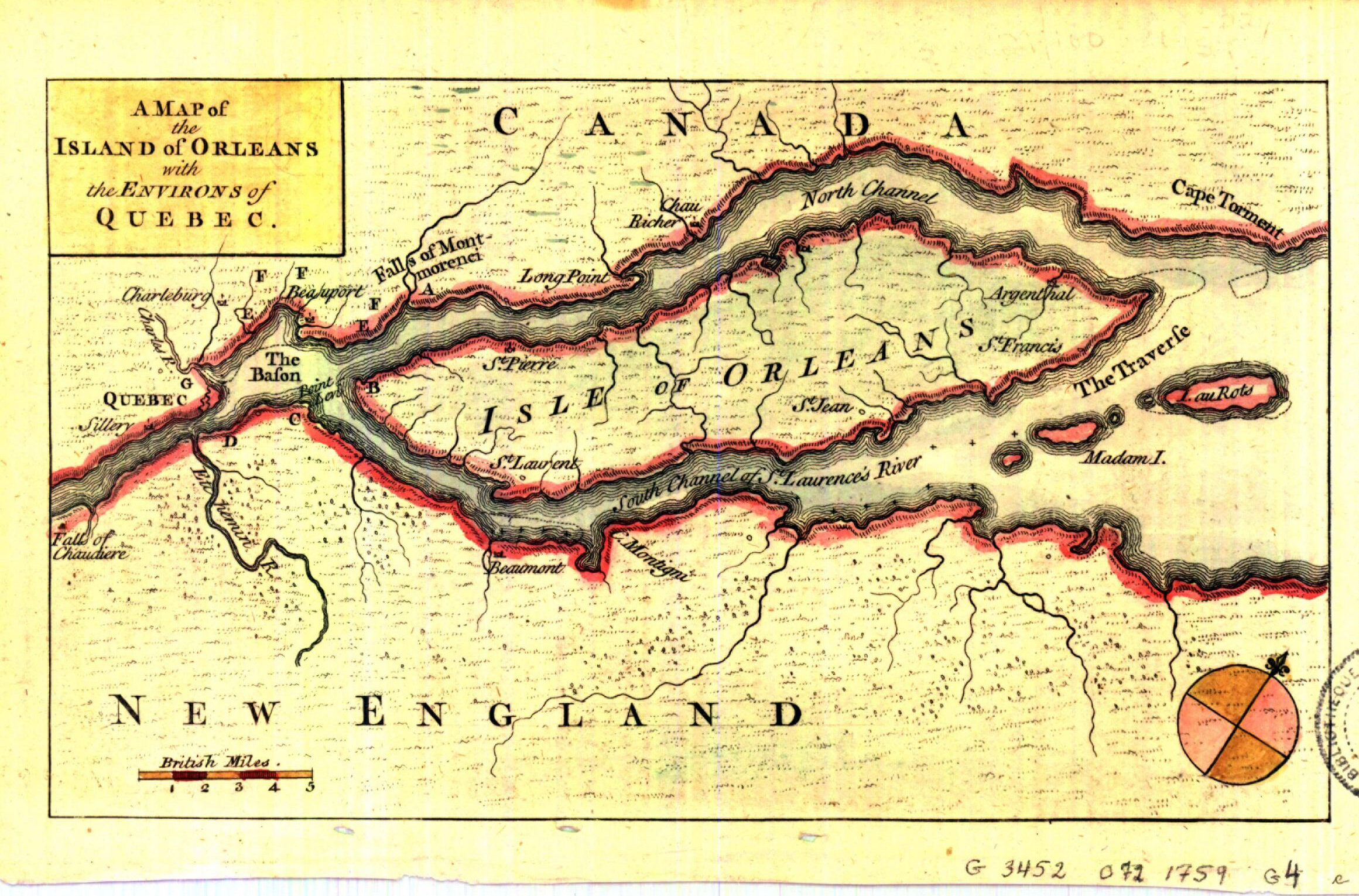

Long before the arrival of Europeans, Île-d'Orléans (“Orleans Island”) was inhabited by indigenous peoples. The Wendat people called it Ahȣendoe, meaning "island," or Laȣendaona Tiatoutarchi, meaning either "island in the big river," "hidden island" or "escape island" (depending on the source). The Hurons called the island Minigo and the Algonquins called it Windigo, meaning "bewitched."

French explorer Jacques Cartier encountered the island and its inhabitants in 1535, during his second voyage to the New World. Accompanied by two indigenous interpreters, Cartier was welcomed by the inhabitants and was gifted fish, millet and melons. At the time, he called it Isle de Bascuz (Bacchus) because of the abundance of grape vines he saw there. Less than a year later, however, he referred to the island as Île-d'Orléans, in honour of Henri II of France, then Duke of Orleans.

The Hurons called the island Île-Sainte-Marie starting in 1651; that name was abandoned with their departure in 1656.

In 1675, the seigneurie on the island was ceded to François Berthelot under the name "Île et comté de Saint-Laurent" (island and county of Saint-Laurent). Called alternatively Île-d'Orléans and Île-Saint-Laurent, the latter name fell out of usage as of 1770.

“The Ile d’Orléans is six leagues long, very beautiful and pleasant due to its diversity of woods, prairies, and grapevines found in several parts; with walnut trees, the tip of the western edge of the island is called Cap de Condé.”

A New Home for European Settlers

Île-d'Orléans is fairly flat and shaped like an oblong, measuring 34 kilometres long and 8 kilometres wide at its broadest. Due to its geographic position just downstream from Québec City and its fertile soil, the island was one of the first areas to be settled in New France. A seigneurie covering the entire island was established in 1636. It was granted to eight partners by the Compagnie de la Nouvelle France. In typical seigniorial fashion, plots of land were laid out in long narrow strips, going from the edge of the St. Lawrence River to the middle of the island (evidence of this pattern can still be seen today). Settlers started to arrive in 1650 and soon some 2,000 inhabitants called the island home. Land clearing began in 1660.

The Saint-Jean Seigneurie on Île-d'Orléans (2015 photo taken by Marc Lautenbacher).

NASA satellite image of Île-d'Orléans showing plots of land in a seigniorial layout (Wikimedia Commons)

The first residents to receive land concessions were the Ursuline nuns, Eléonore de Grandmaison (widow of Antoine Boudier), René Maheu, Jacques Gourdeau (third husband of the aforementioned Grandmaison, he was assassinated in 1663 by one of his servants), Louis D'Ailleboust (governor of Canada from 1648 to1651), Jacques Levrier, Gabriel Gosselin and Claude Charron. In April of 1656, Charles de Lauzon granted land plots from his seigneurie to the following people: Guillaume Beaucher dit Morency, Jacques Perrot, Robert Gagnon, Claude Guyon (Dion), Denis Guyon, Michel Guyon, Pierre Nolin dit Lafeugière, Pierre Loignon/Lognon, Guillaume Landry, François Guyon, Simon Leureau, Louis Côté, René Mézeray dit Nos, Jacques Billodeau and Maurice Arrivé. Shortly after, Pierre le Petit, Gabriel Rouleau dit Sansoucy and Jacques Delugré moved to the island. From 1657 to 1660, land was given to Jean Lehoux, Louis Houde, Adrien Blanquet, Jacques Bernier dit Jean de Paris and Pierre Labrecque.

A map drawn by de Villeneuve clearly lays out all these plots of land alongside their occupants’ names.

Map of the Seigneurie of Île-d'Orléans measured precisely in 1689 by the Sieur de Villeneuve; 347 landowner names are included (Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec)

Betrayal and Massacre of the Hurons

“Huron-Wendat Hunter Calling a Moose" by Cornelius Krieghoff, circa 1868. Wikimedia Commons.

Chased out of their previous territory (the Mission at Huronia) by the Haudenosaunee (then called the Iroquois), the Hurons sought refuge around Québec City and on Île-d'Orléans with the help of missionaries in 1651. Some 400 Hurons settled on the southwestern tip of the island (present-day Anse du Fort), where they constructed a fort guarded by cannons, and renamed the island Île-Sainte-Marie, in honour of their patron saint. They purchased land from Eléonore de Grandmaison, upon which they built cabins and planted corn crops. Unfortunately, their tranquil existence soon came to an end. The Iroquois tracked down the Hurons to their new home in 1654 and, under the guise of peace talks, arranged for several meetings with them and Governor d'Ailleboust. Negotiations took place over the next two years before peace was finally shattered in 1656. On the night of April 19th, under the cover of darkness, the Iroquois attacked the Hurons as they tended to their crops. Seventy-one Hurons were slaughtered or taken prisoner.

The next day, the Iroquois boldly paraded the prisoners at Québec. The governor chose not to intervene, as he didn't want to compromise the fate of the colony. Despite this massacre, the Hurons who remained on the island continued to negotiate with the Iroquois, who promised to spare them if they accepted to live among them. The majority of the Hurons left the island accompanied by the Iroquois, and the men were predictably murdered soon after. The women and children were spared, only to be distributed amongst the Iroquois as slaves. The handful of Hurons who were left on Île-d'Orléans eventually moved closer to Québec City.

The Iroquois didn't focus their aggression solely on rival indigenous nations, however. In 1661, they launched several attacks against French settlements, starting at Montréal, followed by Trois-Rivières, Tadoussac, Beaupré and Île-d'Orléans. Dozens of colonists from the island were either murdered or captured. The governor sent reinforcements from Québec, but they arrived too late. Nine-year-old Anne Baillargeon was one of the captives. She lived among the Iroquois for nine years. After Monsieur de Tracy negotiated the return of all French captives from the Iroquois, Anne reluctantly returned, even trying to escape and return to Iroquois country on one occasion. She was brought to the Ursuline nuns in order to “strengthen her Christian spirit.”

Poulin seigniorial mill from 1668, Sainte-Famille (photo taken circa 1925 by Edgar Gariépy, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Poitou, Normandy & Perche Roots

Between 1660 and 1670, many more land concessions were granted. Many of these settlers, mostly from Poitou, Perche and Normandy, had large families and are therefore the ancestors of many French Canadians. They include Jacques Asseline, Jean Baillargeon, Emery Bellouin (Blouin) dit Laviolette, Charles Allaire, Abel Turcot, Mathurin Chabot, Joseph Bonneau, David Estourneau (Létourneau), René Emond, Grégoire De Blois, Nicolas Godbout, Louis Martineau, François Marceau, Germain Lepage, Nicolas Odet dit Lapointe, Jacques Paradis, François Noël, Jean Prémon and Gabriel Royer.

As of 1666, Île-d'Orléans was inhabited from one end to the other. According to a census conducted that year, the population was 471, making it one of the most populated areas of New France. The island was divided into five main areas, which eventually became parishes: Sainte-Famille (founded in 1661), Saint-Pierre, Saint-François, Saint-Jean (all founded in 1679) and Saint-Laurent (founded in 1698). A sixth parish, Sainte-Pétronille, was founded in 1870. The island's first European inhabitants had to quickly adapt to the weather, new methods of building, and new methods of farming. A mill wasn't constructed until 1667, which meant that residents had to travel to Beaupré to grind their grain.

“The Spinner, Île-d'Orléans". 1927 print by André Biéler. Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec.

The 1681 census enumerated 1,080 people living on the island. By the end of the 17th century, there were as many people living on Île-d'Orléans as there were in Québec City. The island flourished thanks to a thriving agricultural sector. Though self-sufficient at first, the inhabitants eventually started selling their grain crops and fruit in neighbouring Québec. They grew wheat, oats, rye, potatoes, peas and tobacco, and even made high-quality cheese. Fishing was also an important trade: the St. Lawrence river was full of eels, salmon, sturgeon, muskellunge, sea bass and walleye. Inhabitants also hunted pigeons, geese and ducks.

The residents of Île-d'Orléans lived mostly in isolation. Island families intermarried and land was passed down from father to sons. This reality meant that traditions were passed down as well, contributing to the maintenance of ancient customs. In the latter half of the 17th century, the iconic house of Île-d'Orléans was born, with its triangular roof, its opening toward the sunlight and its south-facing orientation.

The English Conquest

Île-d'Orléans was one of the most devastated areas during the war of 1759. When the French learned that English ships were making their way up the St. Lawrence in May, all residents of Île-aux-Coudres and Île-d'Orléans were ordered to evacuate and relocate to Charlesbourg. They were forced to leave their homes, farm animals and crops. Many were ill prepared and hadn't brought enough food to sustain their families. Many died in the chaos. French troops attempted to fortify the island and prevent the English from disembarking but soon realized they were greatly outnumbered. They abandoned Île-d'Orléans in July and retreated to Beauport. As they feared, British ships soon landed on the island and General Wolfe made it his headquarters while he planned his attack. The southwestern tip of Île-d'Orléans offered the perfect vantage point to observe the military activity at Québec. On June 30th, British troops stationed themselves at Pointe-Lévis, across the water from Québec, and bombarded the town. On July 31st, they moved to L'Ange-Gardien and launched another attack on the French at Montmorency. The French troops were well prepared, however, and defeated the British, who retreated to Île-d'Orléans.

Furious, Wolfe ordered the destruction of all villages in the countryside. Homes were gutted and burned, and Île-d'Orléans was not spared. Over 1,400 homes were pillaged, then destroyed. One of the few buildings left standing was the seignorial manor. A museum today, the Manoir Mauvide-Genest, was the home of naval surgeon Jean Mauvide. He had just purchased half of the island's seigneurie when the Seven Years' War erupted. Forced to flee with the rest of the inhabitants, he joined the French troops on the other side of the river. Working as a surgeon on the battlefield, he likely witnessed the destruction and fires on Île-d'Orléans. On the walls of his manor, located at Saint-Jean-de-l’Île-d’Orléans, traces of cannonballs are still visible today. Another building that survived the war was the Drouin house, built circa 1730, which also stands today (both are pictured below).

The Drouin House, Sainte-Famille (2012 photo taken by Selbymay)

The Mauvide-Genest Manor located at 1451 chemin Royal in Saint-Jean (2012 photo taken by Huguette Dion)

On the fateful night of September 13th, Wolfe's troops made their way to l'Anse-au-Foulon and scaled the cliffs onto the Plains of Abraham. French troops, led by the Marquis de Montcalm, faced off against Wolfe's forces, but they were ultimately defeated. Both commanding officers died as a result of their battle-inflicted wounds. After losing Québec, the French effectively lost control of New France. At the end of the war in 1763, France surrendered Canada to the British. Click here to learn more about the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

1797 engraving based on a sketch made by Hervey Smyth, General Wolfe's aide-de-camp during the siege of Québec (Library of the Canadian Department of National Defence)

The residents of Île-d'Orléans returned to their homes, most of them reduced to rubble or ash. Some families built wooden shacks where their house once stood. Three quarters of the island's livestock had perished, and crops were almost completely destroyed. It took many years for each of the communities to rebuild.

Saint-Pierre-de-l’Île-d’Orléans & Sainte-Pétronille

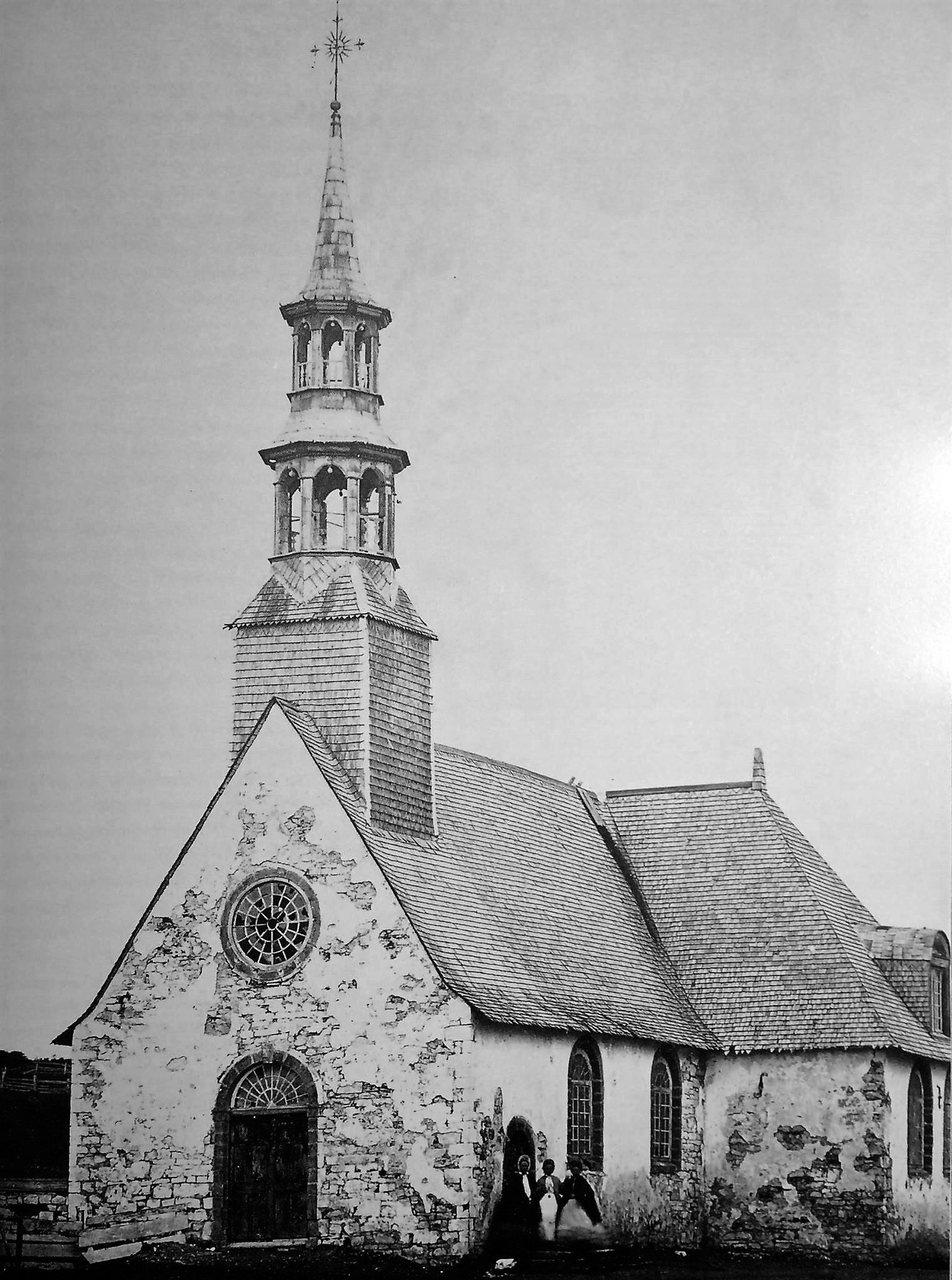

Saint-Pierre is the closest parish to Québec, covering the entire southwestern part of the island. Its first church was constructed near l'Anse du Fort and was consecrated in July of 1653. Jacques Gourdeau and Éléonore de Grandmaison were married there in 1652—likely the first marriage on Île-d'Orléans. Two other churches were built in the parish before the present-day church was constructed in 1769.

The 1652 marriage record for Jacques Gourdeau and Éléonore de Grandmaison, registered at Québec (Ancestry)

A large shipbuilding construction site once existed at l'Anse du Fort. In 1824 and 1825, the ships Columbus and Baron of Renfrew, said to be the largest wooden ships built in the 19th century, were constructed for a Scottish merchant company. They were purposely built quite poorly, as the intent was to take them apart as soon as they docked in Europe so the owners could avoid paying duties on wood. Predictably, the ships did not fare well. After successfully crossing the ocean, the Columbus failed to make it back to North America, probably lost at sea. The Baron of Renfrew sustained major damage on the banks of the Thames and was deemed beyond repair.

“View of the Large Ship Columbus on the day of her launch at the Island of Orleans, 8 miles from Quebec being Wednesday the 28th of July 1824" (Library and Archives Canada)

In 1855, a 150-foot quay was built at the tip of the island near l'Anse du Fort by notary H. N. Bowen. Prior to this, rowboats were the only way to get across the channel to Québec. In the fall of 1855, the first steamboat, called the Petit Coq, started making the crossing two or three times daily. This area eventually became the village of Sainte-Pétronille (founded in 1870). The 1861 census reported 1,022 people living in Saint-Pierre, most of whom were farmers. The remainder were navigators and artisans.

Château Bel-Air in Sainte-Pétronille, circa 1920 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Sainte-Famille-de-l’Île-d’Orléans

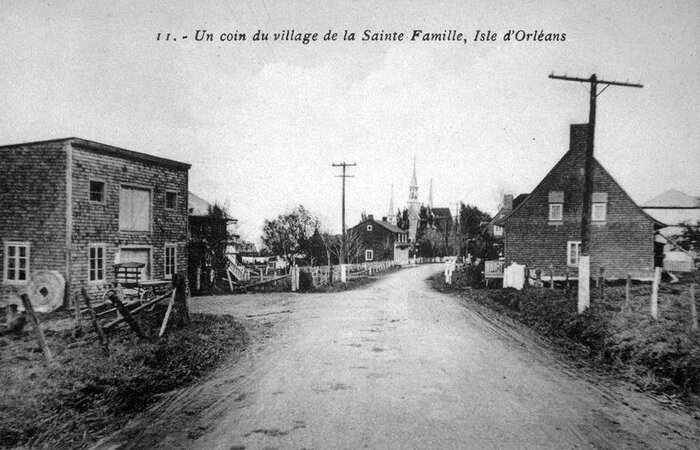

Sainte-Famille-de-l'Île-d'Orléans (circa 1920 photo by M. Prévotat. Wikimedia Commons)

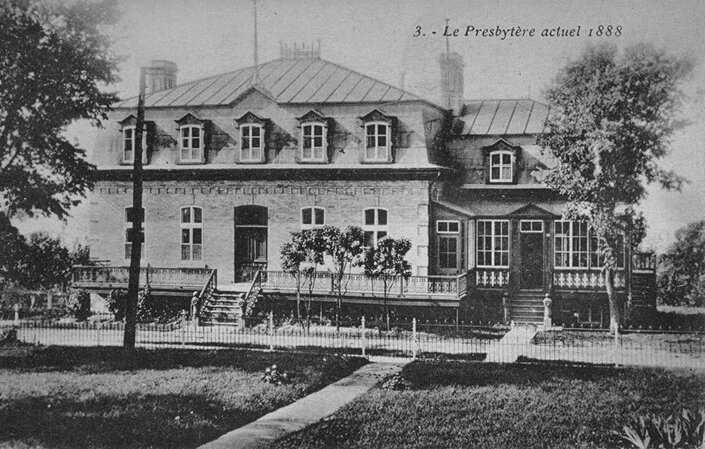

The oldest and most populous of the parishes, Sainte-Famille is located on the north of Île-d'Orléans. The first entry to the parish's records is the 1666 baptism of Barthélémy Landry, son of Guillaume Landry and Gabrielle Barré. Until 1679, there existed only one set of parish books for the entire island. Sainte-Famille is first mentioned by name in a 1671 burial record; Saint-Pierre, Saint-Paul (Saint-Laurent) and Saint-Jean are first mentioned in 1675. The division of the island into parishes probably occurred at this time. Sainte-Famille's first church was erected in 1671. The construction of the existing church started in 1745 and was consecrated four years later.

In 1861, 888 people lived in the parish, most farming hay and raising cattle.

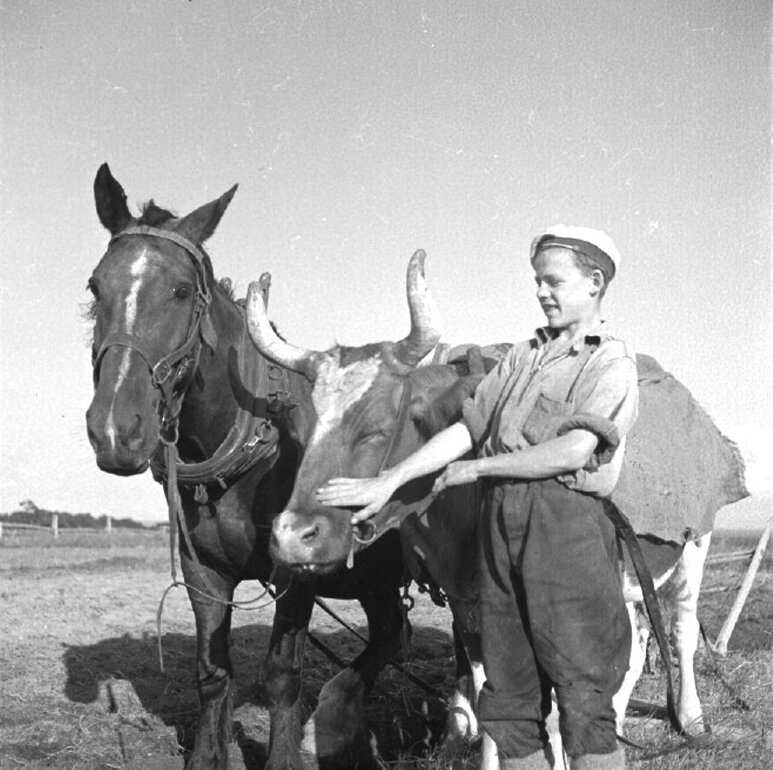

Brothers Joseph, Arthur and Xavier Allaire, on a duck hunt in Saint-François-de-l'Île-d’Orléans, circa 1935 (Wikimedia Commons)

Saint-François-de-l’Île-d’Orléans

The parish of Saint-François encompasses the entire northeastern tip of the island. Parish records started in 1678. A small chapel was built by residents and the first mass took place in 1736. In 1861, 561 people lived in Saint-François, almost all of them farmers. Known for its abundance of game, this part of the island was very popular with hunters.

Saint-Jean-de-l’Île-d’Orléans

The parish of Saint-Jean is located on the southern shores of the island. Construction began on the first parish church circa 1675, but as at 1683 it was still not completed. The start of construction on the current church is said to date from about 1735. It is the largest of the parish churches. In 1861, the village had a population of 1,433. Similar to Saint-Pierre, most heads of households were farmers. The rest were navigators and artisans. Saint-Jean was known for producing navigators, sailors and pilots. In 1830, the first school was established in the parish. In 1858, the village commissioned the building of a quay for the use of its residents. A steamboat service was established, with crossings three times per week.

The Hébert-dit-Lecompte House at 3404 chemin Royal in Saint-Jean (2012 photo taken by Huguette Dion)

Sadly, Île-d'Orléans is well known for its shipwrecks. From its early days, treacherous seas around the island resulted in multiple shipwrecks and dozens dead. The worst tragedy was that of the schooner La St. Laurent, lost in a terrible storm on the river in 1839. Twenty-one sailors lost their lives, 17 of them from the parish of Saint-Jean, sending the entire village into mourning.

Saint-Laurent-de-l’Île-d’Orléans

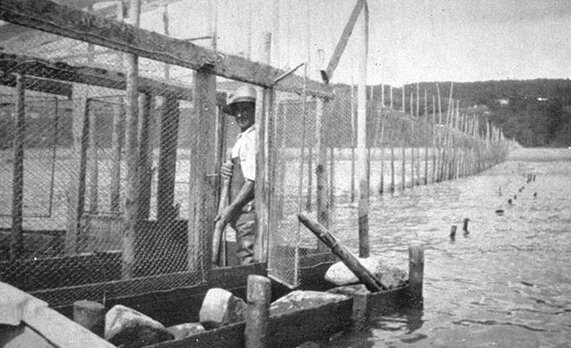

The parish of Saint-Laurent was first called Saint-Paul, a name it kept until 1698. A first church was built in 1675, replaced by a new church some 20 years later. The current church was completed in 1861. According to the census conducted that year, the village had 833 residents, most of whom were farmers. Many also built rowboats.

Dock at Saint-Laurent. Circa 1920. Photo by M. Prévotat. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1774, the chemin Royal (Royal Road) was completed, connecting all parishes on Île-d'Orléans. The main thoroughfare is a 67 km circuit that surrounds the island. Prior to this, Île-d'Orléans was dotted with dirt roads going from house to house, leading to the local mill or parish church. In 1935, a suspension bridge was built to link Île-d’Orléans to Québec.

The Island’s Famous Residents

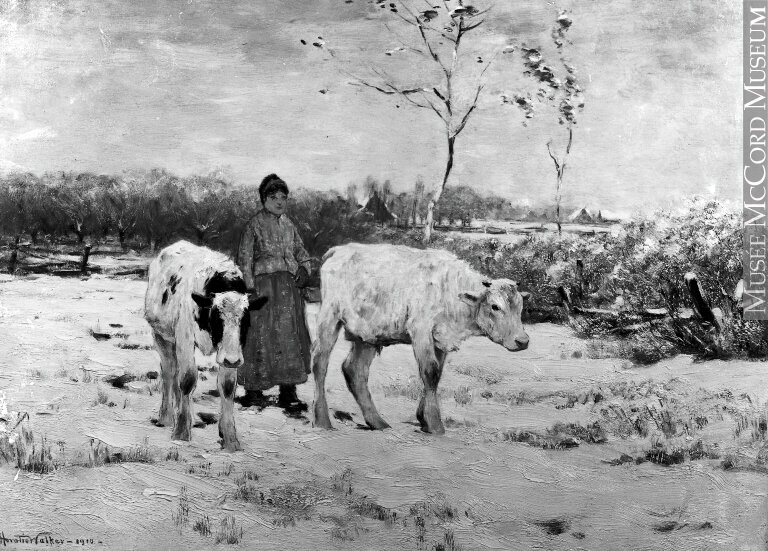

Over the years, many artists have called Île-d'Orléans home, happy to escape the noise and chaos of the city. Horatio Walker lived in Sainte-Pétronille from 1885 until his death in 1938, painting numerous iconic images of the island and earning the nickname "le chantre de l’Île-d’Orléans" (the champion of Île-d’Orléans).

Horatio Walker painting in his garden on Île-d'Orleans in 1933. Wikimedia Commons.

1918 painting by Horatio Walker. National Gallery of Canada.

Swiss painter André Biélier lived on Île-d'Orléans from 1927 to 1930, capturing many scenes of day-to-day rural life in his art. From 1930 to 1933, Québécois artist Marc-Aurèle Fortin created many paintings depicting houses and rural scenes during his summers on the island.

"Procession in Sainte-Famille", 1929 oil painting by André Biéler. National Gallery of Canada.

“Dyeing Wool”, 1928 oil painting by André Biéler. Wikimedia Commons.

Félix Leclerc

Perhaps the most famous resident of them all, singer-songwriter Félix Leclerc immortalized Île-d'Orléans in a song entitled "Le Tour de l'Île", written in 1975. Leclerc first visited the island in 1946 and moved there permanently in 1970. He was buried in the parish of Saint-Pierre in 1988.

Leclerc performing "Le Tour de l'Île" in 1975.

1925 Île-d’Orléans, McCord Museum

Current Statistics:

Population: 7,082 (2016)

Average age of the population: 47.1

Average size of census families: 2.7

Density: 35 inhabitants per square km

Demonym: “Orléanais”

Note: Most of the information on this page is taken from the 1867 book Histoire de l'Île d'Orléans by L.P. Turcotte. We recommend reading it for a deeper dive into the island’s history. See Sources below.

Image Gallery

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you!

Sources and further reading:

Martin Fournier, "Île d'Orléans (patrimoine naturel)", Encyclopédie du patrimoine culturel de l'Amérique française (http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/fr/article-77/%C3%8Ele_d'Orl%C3%A9ans_(patrimoine_naturel).html#.X3TtiJNKgUo), 2007.

Gilles Gallichan, "À la rencontre des villégiateurs de Sainte-Pétronille", Le Devoir (https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/57835/a-la-rencontre-des-villegiateurs-de-sainte-petronille), 28 Jun 2004.

L.P. Turcotte, Histoire de l'île d'Orléans (Québec : Atelier Typographique du "Canadien", 1867). Digitized by Canadiana (https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.23429/3?r=0&s=1). Translated into English by Dr. Elizabeth Blood, Salem State University, Salem, Massachusetts 2019 (https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=fchc).

Statistics Canada. 2017. L'Île-d'Orléans, MRC [Census division], Quebec and Quebec [Province] (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa. Released November 29, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

"Île d'Orléans", Noms et lieux du Québec, Commission de toponymie, Gouvernement du Québec, 1994, digitized at http://www.toponymie.gouv.qc.ca/ct/toposweb/fiche.aspx?no_seq=45799.

"L’île d’Orléans, berceau de l’Amérique française", Radio Canada (article and podcast), https://ici.radio-canada.ca/premiere/emissions/aujourd-hui-l-histoire/segments/entrevue/112432/ile-orleans-michel-lessard.

"Lieu historique national du Canada Seigneurie-de-l'Île-d'Orléans", Le répertoire des désignations d’importance historique nationale, Parcs Canada (https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_fra.aspx?id=709&i=57103)

"Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec", Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Gouvernement du Québec (http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/rechercheImmobilier.do?methode=afficher).