The Story of La Corriveau

Marie Josèphe Corriveau, known to history and folklore as La Corriveau, is one of the most notorious and misunderstood figures in Quebec’s past. Her life and the events surrounding her second husband’s death in 1763 transformed her from a real woman into a symbol of fear, misogyny, and injustice. While folklore branded her a witch and a serial killer, recent historical research has revealed a far more complex story.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

La Corriveau

Marie Josèphe Corriveau, known to history and folklore as La Corriveau, is one of the most notorious and misunderstood figures in Quebec’s past. Her life and the events surrounding her second husband’s death in 1763 transformed her from a real woman into a symbol of fear, misogyny, and injustice. While folklore branded her a witch and a serial killer, recent historical research has revealed a far more complex story.

Roots in Saint-Vallier: Marie-Josèphe’s Early Years

Marie Josèphe Corriveau, the daughter of Joseph Corriveau and Marie Françoise Bolduc, was baptized on May 14, 1733, in the parish of Saint-Philippe-et-Saint-Jacques in Saint-Vallier, in New France. While the baptismal record does not specify her exact birth date, it notes that she was around three months old at the time. Her given name has also been spelled “Josephte.”

1733 baptism of Marie Josèphe Corriveau (Généalogie Québec)

Location of Saint-Vallier (Mapcarta)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

Marie Josèphe was the second of nine children born to Joseph and Marie Françoise. Tragically, eight of the children seem to have died in infancy, making Marie Josèphe the only one to marry and have children of her own. The Corriveau family resided in the village of Saint-Jean-Baptiste, part of the broader parish of Saint-Vallier.

Marie Josèphe’s First Marriage

On November 15, 1749, notary Pierre François Rousselot prepared a marriage contract between 16-year-old Marie Josèphe Corriveau and 23-year-old Charles Bouchard at the home of Joseph Corriveau in Saint-Vallier. Charles, the son of Nicolas Bouchard and Marie Anne Veau dite Sylvain, was also a minor, so both sets of parents provided their consent on behalf of the couple.

The contract followed the Coutume de Paris, the legal code governing property rights in New France. Under this law, married couples were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning that all property acquired during the marriage was jointly owned. In the contract, Charles requested that a 55-arpent plot of land he owned in "the village of Saint-Jean" be included in the community of goods. He also offered Marie Josèphe a prefix dower of 300 livres and set the preciput at 150 livres. [The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him. The preciput was a benefit conferred by the marriage contract, usually on the surviving spouse, granting them the right to claim a specified sum of money or property from the community before the rest was divided.]

The witnesses to the contract included Marie Josèphe’s grandfather, Pierre Corriveau, her uncles François Étienne and Antoine Rémillard, her cousin Jacques Corriveau (militia captain for Saint-Vallier), and her aunts Marie Anne Bolduc and Marguerite Marier. Notably, Marie Josèphe was able to sign the contract, but her husband-to-be could not.

The wedding ceremony followed four days later, taking place on November 19, 1749, in Saint-Vallier.

The last page of Marie Josèphe Corriveau’s 1749 seven-page marriage contract, showing her signature (FamilySearch)

1749 marriage of Marie Josèphe Corriveau and Charles Bouchard (Généalogie Québec)

The newlyweds settled on Charles’s land in Saint-Vallier, where they had three children:

Marie Françoise (1752-1827)

Marie Angélique (1754-1789)

Charles (1757-1791)

In 1757, Marie Josèphe’s parents gave the couple an additional plot of land in Saint-Vallier, measuring one and a half arpents wide by 40 arpents deep, in exchange for a lifetime pension.

Death of Charles Bouchard

Marie Josèphe’s first husband, Charles Bouchard, died at the young age of 34. He was buried on April 27, 1760, in the parish cemetery of Saint-Philippe-et-Saint-Jacques in Saint-Vallier. As was typical for the time, the burial record does not specify a cause of death.

1760 burial of Charles Bouchard (Généalogie Québec)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

As was typical in the challenging environment of New France, Marie Josèphe sought to remarry quickly, as raising three children alone with limited financial resources was a daunting task. Widows often faced greater difficulties in finding a new husband compared to widowers, primarily due to having multiple children and fewer financial resources. However, younger widows had a better chance of remarrying. On average, widows remarried within three years, while widowers typically found new spouses within two years.

Marie Josèphe’s Second Marriage

1761 marriage of Marie Josèphe Corriveau and Louis-Hélène Dodier (Généalogie Québec)

On July 14, 1761, notary Jean Antoine Saillant de Collègien drew up a marriage contract between 28-year-old widow Marie Josèphe Corriveau and 23-year-old farmer Louis-Hélène Dodier at Marie Josèphe’s home in Saint-Vallier. Louis-Hélène was the son of Pierre Dodier and Marie Thérèse Lebrun dite Carrière. Marie Josèphe’s witnesses included her parents, her brother-in-law Pierre Bouchard, and her cousin Joseph Corriveau. As before, the contract adhered to the Coutume de Paris. Louis-Hélène provided a prefix dower of 300 livres for his future wife. Marie Josèphe was able to sign the contract, while Louis-Hélène could not.

The couple was married six days later, on July 20, 1761, in Saint-Vallier.

The couple did not have any children, and their marriage appears to have had a troubled beginning. Less than a year after their wedding, on April 21, 1762, Marie Josèphe’s father, Joseph Corriveau, took Louis-Hélène to court. Following the 1760 conquest of New France, the colony was under British military administration, and Joseph presented his case before the military council. The council ruled against Dodier, forbidding him from mistreating or insulting Joseph and ordering him to pay fines of 12 livres to the General Hospital, along with legal costs amounting to 20 shillings. This incident was one of many disputes between Joseph and Dodier, often centering on issues related to land and a shared horse.

1912 drawing of La Corriveau by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte (Wikimedia Commons)

In December 1762, Marie Josèphe fled her home, reportedly due to mistreatment by her husband. She sought refuge with her uncle, Étienne Veau dit Sylvain, but was eventually forced to return home by Major James Abercrombie, the commander overseeing the south shore of Québec.

A Sudden Death: The End of Louis-Hélène Dodier

Louis -Hélène Dodier died during the night of January 26 to 27, 1763, at the age of 24. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Philippe-et-Saint-Jacques in Saint-Vallier. He had not received confession or last rites due to what was described as a “sad sudden death which has taken him to the other world.”

1763 burial of Louis-Hélène Dodier (Généalogie Québec)

Following Dodier’s death, a coroner’s inquest was conducted by the local priest and militia captain. The body, found in the stable, was initially thought to indicate that Dodier had been trampled to death by horses. However, fuelled by rumours in the village, Governor James Murray ordered the exhumation of the body. Military surgeon Sergeant Fraser examined Dodier’s remains and found severe head injuries inconsistent with a horse’s hoof. Instead, he concluded that the injuries were inflicted by a sharp instrument, possibly a dung fork, raising suspicions of foul play.

Local gossip also pointed to Dodier’s father-in-law, Joseph Corriveau, as a potential suspect, given their history of conflict.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

Accusation and Arrest: The Court-Martial of 1763

About a month after Dodier’s death, Joseph Corriveau was arrested and charged with murder, while his daughter, Marie Josèphe, was charged as an accomplice. Both were imprisoned at the Redoute royale (Royal Redoubt) in Québec as they awaited a court martial before 12 British officers. The trial was set for March 29, 1763, at the Ursulines monastery, “by virtue of a warrant from His Excellency Governor Murray, dated the 28th of said month.” The court martial, presided over by Lieutenant Colonel Roger Morris, sought to address the charges of murder, complicity, and perjury related to Dodier’s death.

"Plans, profils et développement de la redoute Royale," drawing by Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry in 1727 (Archives nationales d'outre-mer, France)

Several witnesses, including local laborers and family members, testified about the longstanding disputes between Dodier and Joseph Corriveau. Some recounted that Joseph had threatened Dodier the day before his death, warning that something terrible would happen if their conflicts were not resolved. The accusations extended to Marie Josèphe, who was alleged to have sought to rid herself of Dodier due to dissatisfaction with the marriage.

Some witnesses claimed that Joseph Corriveau had openly confessed to the murder, while others suggested that Marie Josèphe had conspired with her father. Testimonies also portrayed Dodier’s widow as a woman of questionable morals, with reports of excessive drinking and statements expressing a desire for her husband's death.

In their defense, Joseph Corriveau and his daughter argued that the accusations were based on rumours, personal grievances, and circumstantial evidence. They pointed out inconsistencies in the witnesses' accounts and the absence of concrete proof.

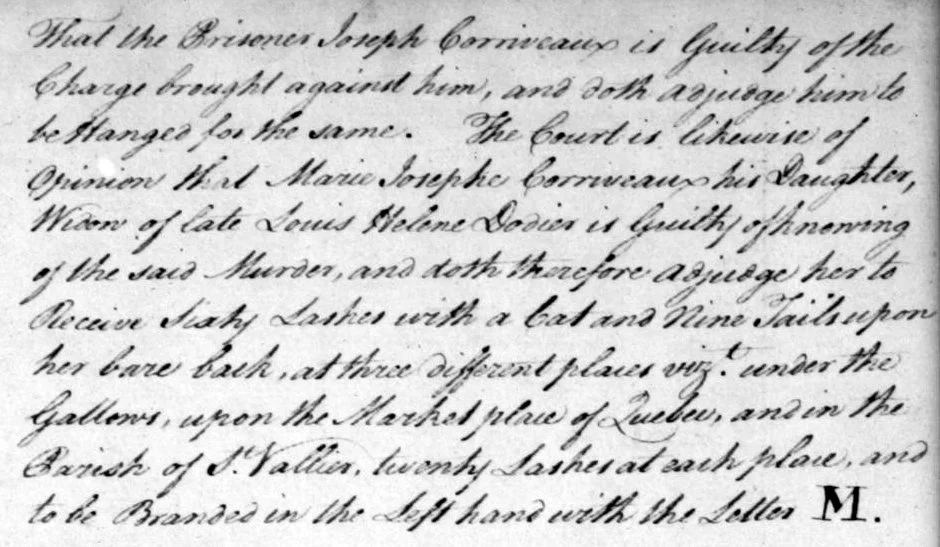

On April 10, the court delivered its verdict:

“That the prisoner Joseph Corriveaux is Guilty of the Charge brought against him, and doth adjudge him to be Hanged for the same. The Court is likewise of Opinion that Marie Josephe Corriveaux his Daughter, Widow of late Louis Helene Dodier is Guilty of knowing of the said Murder and doth therefore adjudge her to Receive Sixty Lashes with a Cat and Nine Tails upon her bare back, at three different places, vizt. under the Gallows, upon the Market place of Quebec, and in the Parish of St. Vallier, twenty Lashes at each place, and to be Branded in the Left hand with the Letter M.”

Sentence of Joseph and Marie Josèphe Corriveau (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

“Cat-o-nine tails, United Kingdom, 1700-1850” (Wellcome Images)

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

The day before his scheduled execution, priest Augustin Louis de Glapion visited Joseph Corriveau to hear his final confession. During this visit, Joseph claimed that he had taken the blame to protect his daughter and that she was the sole perpetrator of the crime. He relayed this confession to the British authorities, prompting a swift reopening of the case and a second trial.

Joseph Corriveau before the courts, illustration by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte (Wikimedia Commons)

On April 15, the day of Joseph's scheduled execution, Marie Josèphe was brought back before the tribunal. Confronted with her father’s admission, she confessed to murdering her husband:

“Marie Josephe Corriveaux, Widow Dodier declared she murdered her Husband Louis Helena Dodier in the night, that he was in Bed asleep, that she did it with a Hatchet; That she was neither advised to it, assisted in it, neither did anyone know of it; She is conscious that she deserves death, only begs of the Court she may be indulged with a little time to Confess and make her peace with Heaven; Adds, that it was indeed a good deal owing to the ill Treatment of her Husband, she was Guilty of this Crime.”

Marie Josèphe’s confession (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Following Marie Josèphe’s confession, the court revised her sentence to death:

“The Court is of Opinion that the Prisoner Maria Josepha Corriveaux Widow Dodier is Guilty of the crime laid to her Charge, and doth adjudge her to suffer death for the same, by being Hanged in Chains wherever the Governor shall think proper.”

Marie Josèphe’s final sentence (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Joseph Corriveau’s sentence was later overturned, and he received a royal pardon. He was subsequently released from prison.

Pardon of Joseph Corriveau (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

On April 18, 1763, Governor Murray instructed Pointe-Lévis militia captain Baptiste Carrier to have his men construct a gallows. The order specified that two trees should be squared to a height of eleven to twelve feet, with a crossbeam placed on top and a ladder at least thirteen feet high. The structure was to be built in the most visible location, ensuring it could be seen by all passersby. Anyone refusing to comply with the order faced punishment.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

A Grim Fate: Execution on Buttes-à-Nepveu

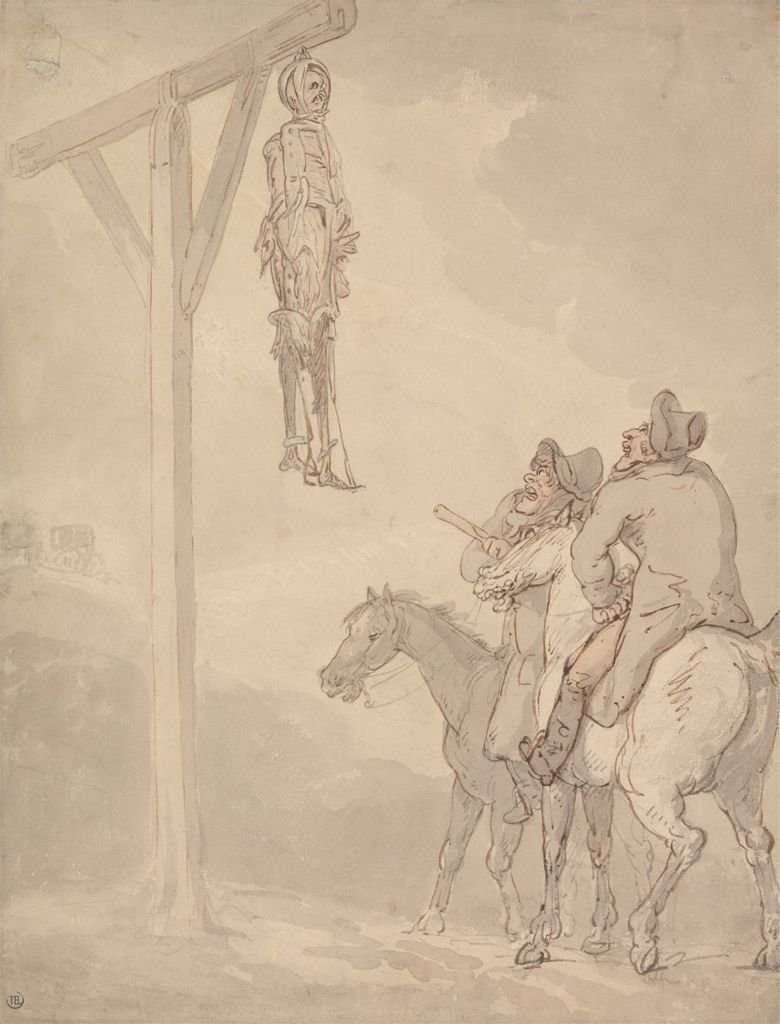

“A Gibbet,” Watercolour by Thomas Rowlandson (Yale Center for British Art)

Likely on the same day, Marie Josèphe Corriveau was led to the gallows on Buttes-à-Nepveu (present-day Parliament Hill, near the Plains of Abraham) and executed by hanging, carried out by executioner John Fleeming.

However, instead of being buried immediately, her body was placed in an iron cage—an act known as gibbetting. This punishment, intended as both a deterrent and a means of intimidating the recently conquered population, was unprecedented in Québec under the French Regime. While gibbetting became more common under British rule, it was typically reserved for the most violent criminals, such as pirates. Following her execution, Marie Josèphe’s body was enclosed in the iron cage and brought by canoe across the St. Lawrence River to the south shore. Upon reaching Pointe Lévy, English soldiers transported the cage to its designated location.

The cage, crafted by blacksmith Richard Dee, was hoisted onto a scaffold at a crossroads (present-day Saint-Joseph and de l'Entente streets) in Saint-Joseph-de-la-Pointe-de-Lévy (now Lévis). Its presence frightened children and outraged villagers, as the sight of a decaying body swinging in a creaking cage became a haunting symbol. This macabre scene fueled the ghost stories and folklore that persist to this day.

La Corriveau, in her iron cage, terrifying a traveller riding a horse, drawing by Arthur Guindon, between 1910 and 1923 (Wikimedia Commons)

"La Corriveau," sketch by Henri Julien, before 1916 (Wikimedia Commons)

The skeleton of "La Corriveau", in her iron cage, terrifying a traveller, from Charles Walter Simpson’s Légendes du Saint-Laurent (Wikimedia Commons)

After being displayed for five weeks, Governor Murray permitted the cage’s removal on May 25, with instructions to bury it “où bon vous semblera” (where you see fit). Marie Josèphe Corriveau’s body was finally buried near the church of Saint-Joseph in Lévis.

The nickname La Corriveau likely emerged in the decades following Marie Josèphe Corriveau’s execution in 1763, as her story became embedded in local folklore.

The ordinance of Governor Murray, permitting the removal of the “Veuve Dodier’s” body, on May 25, 1763 (Université de Montréal)

The Rediscovery of La Corriveau’s Cage

In 1851, gravediggers in the cemetery of the church of Saint-Joseph in Lévis uncovered the iron cage of Marie Josèphe Corriveau, reportedly containing several bones. Recognizing its potential as a money-making attraction, entrepreneurs began exhibiting the cage on a North American tour, embellishing the story of La Corriveau’s crimes along the way. In Montréal, it was displayed at the home of Mr. Leclerc, while in Québec, Mr. Hall charged 15 cents admission for viewing it.

Remarkably, the cage then crossed the border to New York City, where it was exhibited for several days. During its time in New York, it was purchased by P.T. Barnum (of circus fame) for display in his American Museum at Broadway and Ann Street. It later became part of the collection of Moses Kimball’s Boston Museum. In 1899, the cage was donated to the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts, and later became part of the Peabody Essex Museum’s collection.

Article in La Minerve on August 7, 1851, spreading a rumour that Marie Josèphe Corriveau killed "her first two husbands by pouring molten lead into their ears" (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Ad in Le Canadien on August 15, 1851, for the exhibition of the iron cage, which claimed Marie Josèphe Corriveau “was guilty of murdering three husbands” (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Ad in the New York Daily Tribune on August 26, 1851, claiming that Marie Josèphe Corriveau “murdered three successive husbands” (Library of Congress)

Imaginary representation of La Corriveau's cage in a display case at the Boston Museum, 1912 illustration by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte (Wikimedia Commons)

In 2011, the iron cage was rediscovered by chance at the Peabody Essex Museum by Lévis tour guide Claudia Méndez, a member of the Société d’histoire de Lévis. The cage was then returned to Canada, where it was displayed for several years in Lévis. It was later transferred to the Centre national de conservation et d’étude des collections des Musées de la civilisation in Québec for further analysis.

Marie Josèphe Corriveau's gibbet on display at Maison Chevalier in Quebec City in November 2015 (photo by Fralambert, Wikimedia Commons)

In an October 26, 2015, press release, the Centre confirmed that the “the object in question was the one used to display the body of Marie-Josephte Corriveau in 1763.” Although the cage is now a permanent part of the collection at the Musée de la civilisation in Québec, it has only been exhibited periodically to prevent degradation.

"Gibbet used in St. Vadier [sic for St. Vallier] near Quebec in 1763 for the body of Mdme. Dodier hung for murder of her husband. Exhumed in 1850 [sic for 1851] and sold to the Boston Museum theater and after that was given up-sent to the Essex Institute." Photo taken for the Essex Institute, between 1899 and 1916 (New York Public Library).

The Making of a Legend: La Corriveau in Literature and Art

The 1851 rediscovery of La Corriveau’s cage captivated 19th-century authors and artists, transforming her story into a sensationalized legend. Oral tradition now depicted her as a witch who had killed seven husbands. In one novel, she became a ghost haunting passers-by at the crossroads where her cage once stood, while in another, she was portrayed as a professional poisoner. Over the years, dozens of works have been inspired by her tale, including novels, drawings, paintings, sculptures, songs, films, documentaries, plays, and even a ballet. The enduring fascination with La Corriveau continues to shape Quebec's cultural landscape.

In 2015, Canada Post released a Haunted Canada series featuring a stamp with La Corriveau and her cage. Microbrasserie Le Bilboquet even named a beer in her honour, further cementing her place in popular culture.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Oct 2024)

A Complex Legacy

La Corriveau, sculpture by Alfred Laliberté, between 1927 and 1931 (Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec)

The transformation of Marie-Josephe Corriveau’s story reflects significant shifts in historical interpretation in Québec over recent decades. Traditionally, La Corriveau was depicted as a sinister witch or serial killer, symbolizing female malice and evil. However, historians have since uncovered a more nuanced and complex narrative, especially with the discovery of original trial documents and a reconsideration of the historical context.

In the 20th century, interest in social history and women’s roles in early Quebec society prompted historians to reassess her story. In the 1990s, historian Catherine Ferland and others delved deeper into the trial records, revealing that many of the details had been misinterpreted or exaggerated over time. La Corriveau was accused of killing her abusive husband, not of serial killings or witchcraft. Moreover, her trial raised questions about fairness, suggesting it may have been affected by biases related to gender, class, and local politics. The likelihood of a fair trial was further diminished by the circumstances: a military occupation and a tribunal of British officers who did not speak French.

With these discoveries, La Corriveau’s public image has shifted from that of a murderous villain to a symbol of injustice and misogyny. Many now see her as a victim of an oppressive legal system, one that was particularly harsh on women. As a result, modern portrayals of La Corriveau in literature, theatre, and other media have become more sympathetic and humanizing.

While her legend continues to captivate the imagination, it is now framed as a cautionary tale about the dangers of historical bias, rather than as a story of a malevolent witch.

The following video presents an animated retelling of Une Relique: La Corriveau, a classic short story by French-Canadian writer Louis-Honoré Fréchette, originally published in 1913. As with many works of that era, it contains several historical inaccuracies.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_naissances/102118 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), baptism of Marie Josephe Corrivaux, 14 May 1733, St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques), Lévis-Bellechasse, Québec, Canada ; citing original data : Institut généalogique Drouin and PRDH.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/102780 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), marriage of Charles Bouchard and Marie Josephe Corivau, 19 Nov 1749, St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques), Lévis-Bellechasse, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/340524 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), burial of Charles Couiliard, 27 Apr 1760, St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques), Lévis-Bellechasse, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/340625 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), marriage of Louis Dodier and Marie Josephe Corivault, 20 Jul 1761, St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques), Lévis-Bellechasse, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/199654 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), burial of Louis Dodier, 27 Jan 1763, St-Vallier (St-Philippe-et-St-Jacques), Lévis-Bellechasse, Québec, Canada.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) online database, (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/16420 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), dictionary entry for Joseph CORRIVEAU and Marie Francoise BOLDUC, union 16420.

“Actes de notaire, 1737-1756 : Pierre-François Rousselot," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LJ-B814?cat=1020096&i=2193 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), marriage contract of Charles Bouchard and Marie Josèphe Corriveau, 15 Nov 1749, images 2194 to 2200 of 3406 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Actes de notaire, 1750-1776 : Jean-Antoine Sailland," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-R3LF-PZ5W?cat=963721&i=2359 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), marriage contract of Louis Helene Daudier and Marie Josèphe Corriveau, 14 Jul 1761, images 2360 to 2366 of 3351 ; citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Fonds Conseil militaire de Québec - Archives nationales à Québec," online database, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/394834 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), "Entre Joseph Corriveau, demandeur et le nommé Dodier, défendeur. Le Conseil défend audit Dodier de maltraiter ou injurier le demandeur et le condamne à 12 livres d'amendes applicable à l'Hopital général et aux dépens liquidés à 20 shillings," 21 Apr 1762, reference TL9,P4272, Id 394834 ; citing original data : Pièce provenant du registre du Conseil militaire de Québec, registre 4 (28 novembre 1761 - 5 février 1763) f. 80-80v.

“Collection Centre d'archives de Québec - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/366859 : accessed 17 Oct 2024), "Document concernant la Corriveau," 1763-28 Feb 1939, reference P1000,S3,D435, Id 366859, 128 pages; citing original data : originals at War Office, London.

James Murray, Ordonnances, ordres, reglemens et proclamations durant le gouvernement militaire en Canada, du 28e oct. 1760 au 28e juillet 1764, Direction des bibliothèques, Université de Montréal (https://calypso.bib.umontreal.ca/digital/collection/monographies/id/2836 : accessed 23 Oct 2024).

“Invitation à la presse - La cage de la Corriveau. De la noirceur à la lumière," press release, Musée de la Civilisation, digitized by CNW Telbec (https://web.archive.org/web/20151126105911/http://www.newswire.ca/fr/news-releases/invitation-a-la-presse---la-cage-de-la-corriveau-de-la-noirceur-a-la-lumiere-537061251.html : archived, accessed 22 Oct 2024).

“Corriveau, Marie-Josephte,” Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec (https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=26793&type=pge : accessed 22 Oct 2024).

André Lachance, Vivre, aimer et mourir en Nouvelle-France; Juger et punir en Nouvelle-France: la vie quotidienne aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Montréal, Québec: Éditions Libre Expression, 2004), 38-40.

Luc Lacourcière, “CORRIVEAU (Corrivaux), MARIE-JOSEPHTE, known as La Corriveau,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 (https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/corriveau_marie_josephte_3E.html : accessed 22 Oct 2024), University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.

Yvan-M. Roy, "Le 18 avril 1763, Marie-Josephte Corriveau entre dans la légende" (http://yvanm.eklablog.com/la-corriveau-le-18-avril-1763-marie-josephte-corriveau-entre-dans-la-l-a92773763 : accessed 25 Oct 2024), originally published in the magazine La Seigneurie de Lauzon, No 128, Spring 2013.

John A. Dickinson, "La Corriveau", l'Encyclopédie Canadienne, Historica Canada (www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/corriveau-la : accessed 22 Oct 2024), 15 Dec 2013.

"[EN IMAGES] Au-delà de la légende, voici 7 faits historiques sur La Corriveau," Le Journal de Québec (https://www.journaldequebec.com/2023/04/02/en-images-au-dela-de-la-legende-voici-7-faits-historiques-sur-la-corriveau : accessed 22 Oct 2024).

André Pelchat, "Découverte macabre : Une cage en fer ressuscite l’histoire de La Corriveau — la sorcière du folklore québécois," Histoire Canada (https://www.histoirecanada.ca/consulter/canada-francais/decouverte-macabre : accessed 25 Oct 2024), published online 9 Oct 2024, originally published in Canada’s History magazine, Dec 2018-Jan 2019.