Arquebusier

Was your ancestor an arquebusier or harquebusier? Learn what this occupation was like in New France and Canada.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

The Arquebusier

In its simplest sense, the arquebusier (sometimes spelled 'harquebusier') was a soldier armed with an arquebus, an early form of long gun that was used in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Close-up of the Jardin des arquebusiers in Vue de la Bastille et de ses environs en 1789 (View of the Bastille and its surroundings in 1789) by Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris (present-day de la Roquette street, close to Place St Antoine and the Bastille).

Around 1460 in France, the canon à main (hand cannon) was introduced. This weapon soon evolved, first becoming known as a couleuvrine (culverin), then a hacquebute (hackbut), and finally an arquebuse (arquebus). By 1575, the French guild of arquebusiers was established in Paris. To become a master arquebusier, one had to forge a rouet (a metal wheel that was a crucial part of the arquebus) as well as an arquebus barrel that measured three and a half feet in length. Once completed, the weapon had to pass a rigorous test: the barrel would be filled with gunpowder weighing twice that of an ordinary cannonball and then fired. The guild petitioned the king for a dedicated space to conduct these trials, requesting that captains, gentlemen, and even children be permitted to fire the arquebuses on the first Sunday of every month. The king granted their request, and a space was designated as the Jardin des Arquebusiers, which can still be found on historical maps of Paris. Thus, in its historical context, the term arquebusier in France referred not only to those who used the weapon but also to those who crafted it.

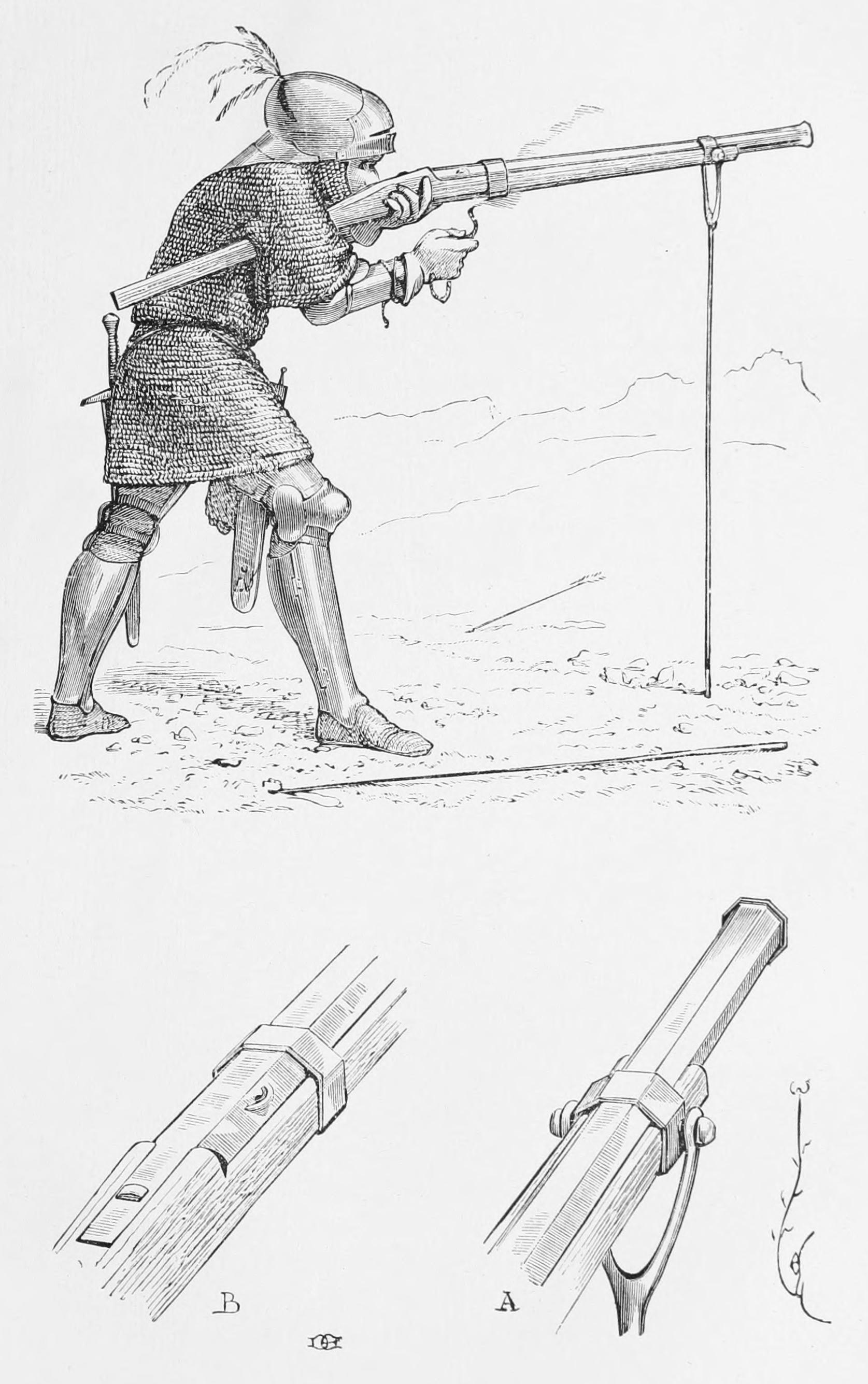

1874 drawing by Viollet-le-Duc appearing in Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque carlovingienne à la Renaissance - illustration Tome 6 (Wikipedia Commons)

According to Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des sciences et métiers (edited from 1751 to 1777), the arquebusier was an artisan who made portable firearms, including muskets, arquebuses, guns, and pistols. His craft allowed him to forge cannons and lock plates, which were then mounted on a wooden stock.

Similar to the armurier (gunsmith), the profession of arquebusier was not exactly the same in New France as it was in the old country. Weapons were, for the most part, not manufactured in New France. The arquebusier performed simplified tasks, primarily due to the lack of specialized tools in the colony. Historians have hypothesized that gunsmiths and arquebusiers in New France did not manufacture complete firearms, as they lacked the precision tools and machinery available in Europe. Instead, they used a variety of small instruments to make and repair different parts of firearms. This lack of precision tools may have been deliberate on the part of the French royalty, intended to maintain a monopoly on weapons manufacturing and thereby exercise control over the circulation of armaments.

The arquebusier was one of seven main metalworking occupations in New France, alongside the locksmith, blacksmith, tinsmith, coppersmith, edge-tool maker, and gunsmith.

Drawing of a Mounted Austrian Arquebusier, late 16th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art (Wikipedia Commons)

The terms arquebusier and gunsmith were often used interchangeably. When examining an ancestor’s vital or notarial records, one might find that a gunsmith was identified as an arquebusier, and vice versa, in various documents.

Arquebusiers in New France: Jean Badeau, Théophile Barthe, Guillaume Beaudry dit Desbuttes, Henri Bélisle, Pierre Belleperche, Barthélémy Bertaut/Berteau, Jean Bousquet, Guillaume Cavelier/Le Cavelier, Jacques Cavelier, Robert Cavelier dit Deslauriers, Claude Chasle, François Comeau, Jean Guy dit Le Rouvier, Bernard de Landaboure, Jean de Lespinace, Jean de Noyon, Étienne Desainctes/Desainte, Nicolas Doyon, Gilles Dutartre dit Lacave, René Fezeret, Pierre Gabourit/Gaboury, Nicolas Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Joseph Genaple de Bellefond, Simon Guillory, Ange Guion/Guyon, Paul Guion/Guyon, Léonard Jean Baptiste Hervieux, Jacques Jouiel/Joyal dit Bergerat, François Lamoureux dit St-Germain, Jérôme Langlois, Antoine LeBoesme dit Lalime, Louis Lecomte dit Dupré, Jean Lemire, Louis Martin, Pierre Maurache/Morache, Étienne Montreuil, François Morneau, Jean Morneau, Joseph Parent, Yves Pinet, Jean Poisson, Pierre Porteret, Nicolas Pré (or Prayé), Pierre Prudhomme, Olivier Quesnel, Nicolas Sarazin, Jean-Baptiste Soulard (Sr. and Jr.), Pierre Soulard (Sr. and Jr.), Jacques Théberge/Thivierge, Louis Trafton, René Vallet, Jacques Villiers.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Alfred Franklin, Dictionnaire historique des arts, métiers et professions exercés dans Paris depuis le treizième siècle (Paris, H. Welter, 1906), 43-44.

Russel Bouchard, Les Armuriers de la Nouvelle-France, Série Arts et métiers, Ministère des Affaires culturelles (Québec, Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 1978), 159 pages.