Jacques Miville dit Deschênes & Catherine de Baillon

Discover how Swiss roots and royal ancestry combine in the story of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon, linking many French-Canadians to Charlemagne and European royalty.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Jacques Miville dit Deschênes & Catherine de Baillon

Discover how Swiss roots and royal ancestry combine in the story of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon, linking many French-Canadians to Charlemagne and European royalty.

Jacques Miville dit Deschênes, son of Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse and Charlotte Mongis, was baptized on May 2, 1639, in the parish of Saint-Hilaire in Hiers, Saintonge, France. The village is now known as Marennes-Hiers-Brouage, located in the Charente-Maritime department. According to his baptism record, Jacques’s parents were living in Brouage at the time, with his father identified as “souice de nation” (of Swiss nationality). Jacques’s godparents were Isaac Miville and Salomée Lomène.

Brouage, located about 50 kilometres south of La Rochelle, was also the likely birthplace of explorer Samuel de Champlain, the founder of Québec. This fortified city was originally established in the 16th century as a hub for the salt trade. Today, the area of Marennes-Hiers-Brouage is home to around 6,000 residents.

1639 baptism of Jacques Miville (Archives de la Charente-Maritime)

Church of Saint-Hilaire in Marennes-Hiers-Brouage (photo by Llann Wé², Wikimedia Commons)

Location of Marennes-Hiers-Brouage in France (Mapcarta)

1630 map of Brouage and its fortifications (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Postcard of Brouage, circa 1920-1930 (Geneanet)

The Miville Family's New Beginning

When Jacques was 10 years old, his family emigrated from France to Canada, a colony in New France. The Miville family arrived in Québec during the summer of 1649, likely aboard the Grand Cardinal or the Notre-Dame. The children in the family were Jacques, François, Marie, Marie Aimée, Marie Madeleine, and Suzanne.

1632 map of New France by Samuel de Champlain (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The family first settled in the seigneurie of Lauzon, on a cliff facing the Plains of Abraham, near what is now Saint-David-de-l'Auberivière. This land was granted to them by the governor of New France, Louis d'Ailleboust de Coulonge, on October 29, 1649. On the same day, Pierre also received a land concession near Québec on chemin Saint-Louis (now Grande-Allée).

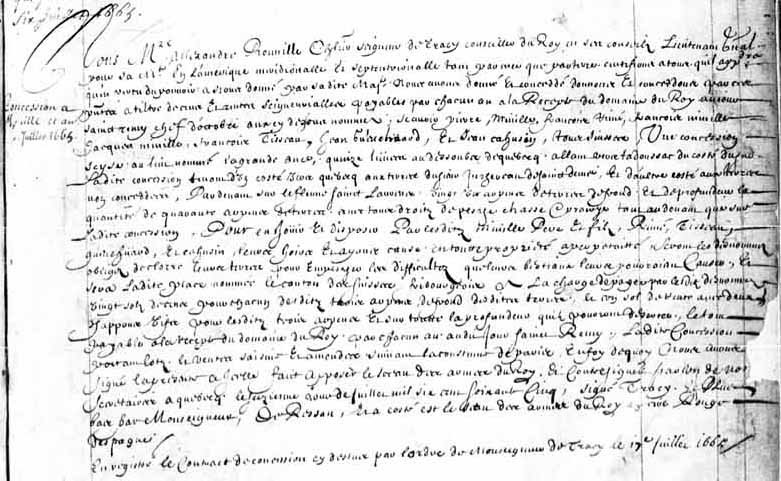

On July 16, 1665, Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, then lieutenant-general of America, granted a large tract of land to several men of Swiss origin: Pierre Miville, his sons François and Jacques, along with François Tisseau, Jan Gueuchuard, François Rimé, and Jean Cahusin. This area was named the Canton des Suisses fribourgeois, after Fribourg, a canton in Switzerland and Pierre Miville's birthplace. The land concession spanned 21 arpents in frontage along the river and 40 arpents in depth, equally divided among the seven men. It was located in a place known as Grande-Anse, which extended approximately 15 kilometres between Saint-Roch-des-Aulnaies and Rivière-Ouelle, “15 leagues below Québec toward Tadoussac on the south side.”

1665 concession of the Canton des Suisses fribourgeois (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The 1667 census of New France shows Pierre and Charlotte living on the côte de Lauzon with their son Jacques and a domestic servant named Le Lorain. At that time, Pierre owned eight head of cattle and had 30 arpents of land under cultivation.

1667 census for the Miville family (Library and Archives Canada)

In 1668, three members of the Miville family—Pierre, Charlotte, and their son Jacques—were summoned by the Conseil Souverain to testify in the case of Jacques Bigeon, who was accused of murdering Nicolas Bernard. At the time of Bernard's death, Jacques was serving as a neighborhood captain on the côte de Lauzon. On that fateful January day, Bigeon told Jacques and another neighbor, Antoine Dupré, that Bernard had been killed by a tree Bigeon had chopped down. After examining the body and questioning Bigeon, Jacques and Dupré reported the incident to a judge in Québec. Following testimonies from several witnesses, including the Miville family, and further interrogations—along with the torture of Bigeon—he was found guilty and executed.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Aug 2024)

A year later, on October 14, 1669, family patriarch Pierre Miville passed away at his home on the côte de Lauzon. He was buried the next day in the Notre-Dame parish cemetery in Québec.

Catherine de Baillon, the daughter of Alphonse Baillon, seigneur de Valence et de la Mascotterie, and Louise de Marle, seigneuresse of Ragonant, was born around 1645 in Les Layes, Île-de-France, France (now Les Essarts-le-Roi, Rambouillet, Yvelines, France). Catherine came from a noble French family and was a descendant of several European monarchs, including Charlemagne (through three distinct lines) and Byzantine emperors.

Catherine and her parents in the de Marle genealogies, part of the Fonds d'Hozier. Held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, the Fonds d'Hozier contains genealogical files created in the 17th and 18th centuries. These files were ceded to the king by Charles d'Hozier in 1717 and are organized alphabetically by family names. The documents and genealogies were submitted to prove noble status in order to receive benefits from the crown.

Close-up of Catherine and her parents’ names in the de Marle genealogies

Aerial view of Les Essarts-le-Roi, 1960 postcard (Geneanet)

Les Essarts-le-Roi, 1904 postcard (Geneanet)

Location of Les Essarts-le-Roi in France (Mapcarta)

Catherine was one of the few nobles sent to New France as a fille du roi ("daughter of the king"). Leaving the port of Dieppe in June 1669 aboard the Saint-Jean-Baptiste, she arrived in Québec that September, along with 148 other Filles du roi. Her reasons for leaving France remain a mystery, though some authors have speculated that she may have been rejected by her family for unknown reasons.

The beautiful Filles du roi mural, painted by Annie Hamel on a wall of the Saint-Gabriel school in Pointe-Saint-Charles, Montréal (© The French-Canadian Genealogist)

For those interested in tracing the European ancestry of Catherine de Baillon, I recommend purchasing the Table d'ascendance de Catherine Baillon from the Société généalogique canadienne-française.

The Marriage of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon

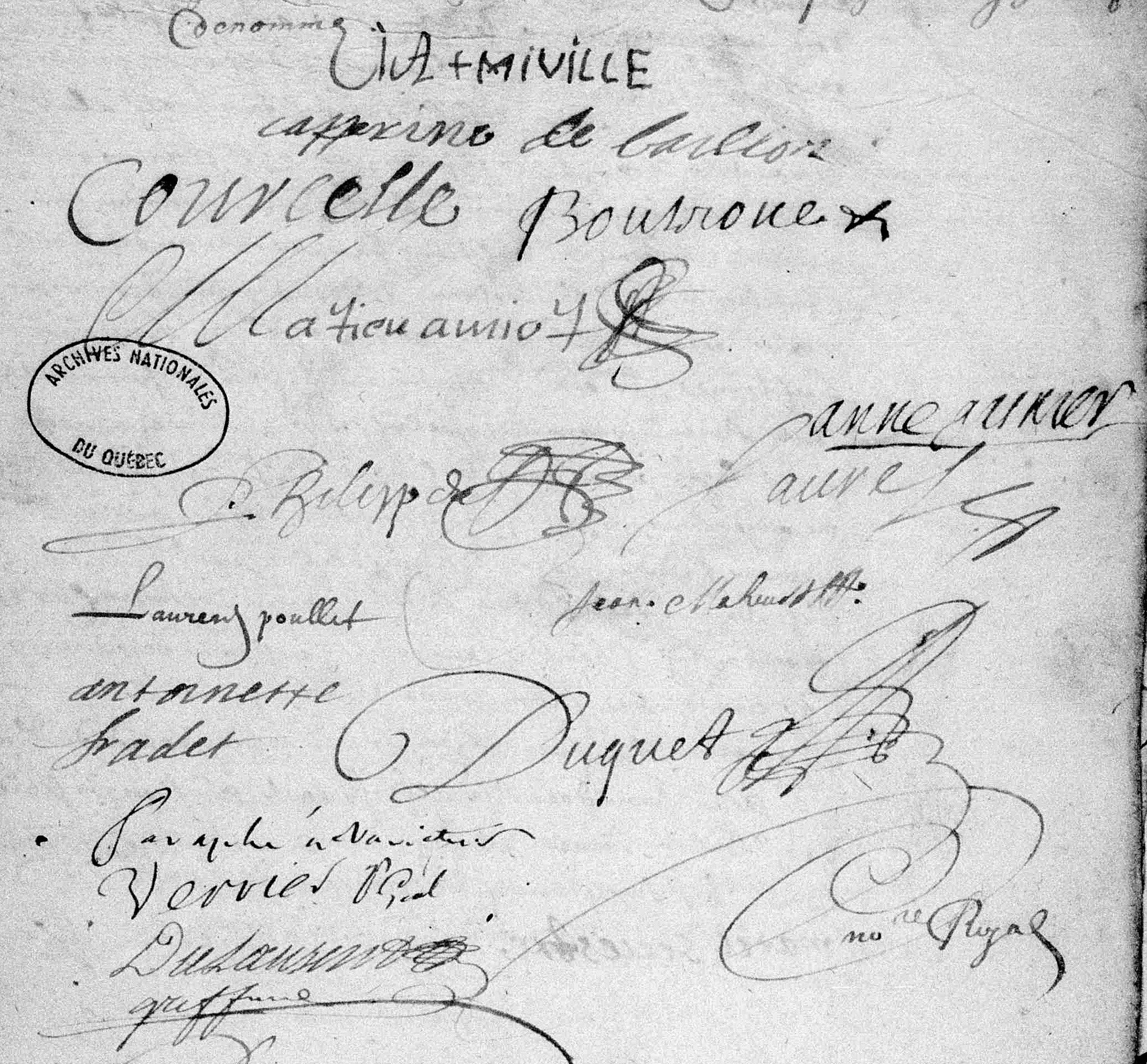

On October 19, 1669, Jacques Miville, “sieur des Chesnes,” and Catherine de Baillon made their way to the office of notary Pierre Duquet de Lachesnaye in Québec. The couple had their marriage contract drawn up before several prominent witnesses. Jacques’s witnesses included his mother, Charlotte, and his siblings: François (and his wife, Marie Langlois), Marie (and her husband, Mathieu Amyot, sieur de Villeneuve), and Aimée (and her husband, Robert Giguère). Also present were Philippe, sieur de la Fontaine, and his wife, Charlotte Giguère, along with sieur Jean Maheu, a bourgeois, and his wife, Marguerite Corriveau. Catherine’s witnesses included Daniel de Remy Chevalier, seigneur of Courcelles and governor of New France, Pierre de Saurel, a captain in the Carignan-Salières regiment, Louis Rouer, sieur de Villeray, a notary and councillor to the king on the Sovereign Council, sieur Laurent Paulet, captain of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste (the ship Catherine traveled on), and Antoinette Fradet. Both the bride and groom were able to sign their names.

The contract followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The prefix dower was set at 1,000 livres, and the preciput at 500 livres.

The Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) governed the transmission of family property in New France. Whether or not a couple had a marriage contract, they were subject to the “community of goods,” meaning all property acquired during the marriage became part of the community. Upon the death of the parents, the community property was divided equally among all children, both sons and daughters. If one spouse died, the surviving spouse retained half of the community property, while the other half was shared among the children. When the surviving spouse passed away, their share was also divided equally among the children.

The dower referred to the portion of property reserved by the husband for his wife in the event she outlived him. The preciput, under the regime of community of property, was a benefit conferred by the marriage contract, usually on the surviving spouse, granting them the right to claim a specified sum of money or property from the community before the rest was divided.

Catherine brought 1,000 livres of goods to the marriage, of which 300 went into the couple’s “community of goods.” This was a considerable sum, since most Filles du roi had little or no dowries, aside from the 50 livres provided by the king.

Signature portion of the 1669 marriage contract of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon (FamilySearch)

Jacques and Catherine published their marriage banns, declaring their intention to marry, on October 20, 27, and 28. They were married on November 12, 1669, in the parish of Notre-Dame in Québec. At the time, Jacques was 30 years old, and Catherine was about 24.

Marriage of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon (Généalogie Québec)

The couple initially settled on the côte de Lauzon and had seven children:

Marie Catherine (1670-1715)

Charles (1671-?)

Jean (1672-1711)

Marie Louise (1675-1754)

Charles (1677-1758)

Marie Claude (1681-?)

Robert (ca. 1683-1758)

Just two days after signing his marriage contract, Jacques asked the same notary to draft an agreement for work on his land at Grande-Anse. He agreed to pay Raymond Cornut and Jean Boudeau 20 livres for each arpent of land they cleared of trees, with the condition that each tree be cut into logs measuring nine to ten feet in length.

O On April 10, 1670, Jacques hired sailor Jean Cazenave (or Casseneuve) to perform navigation and other tasks for him for the sum of 120 livres. [The duration of the engagement is unclear.]

Donation to the Sainte-Anne Confraternity

On July 18, 1670, Jacques and François Miville, along with their mother Charlotte, made a donation to the Confrérie de Sainte-Anne in Québec for the decoration of the Sainte-Anne chapel. The donation, amounting to 80 livres and 6 sols, was given “driven by devotion to Saint Anne” and recorded by notary Pierre Duquet. In return, the Confrérie promised to hold a Requiem Mass within eight days for the repose of the soul of the late Pierre Miville.

A Disastrous Fur Trading Venture

In the fall of 1669, shortly after Pierre Miville’s death, his widow Charlotte and their two sons, Jacques and François, formed a partnership to engage in the fur trade. Unfortunately, the decision turned disastrous. The trio purchased merchandise on credit, valued at 4,691 livres and 16 sols, which they planned to trade with Indigenous peoples for furs. However, due to the poor conditions that year—"both because of the death and illness of the savages, and the lack of sufficient snow for hunting"—they were only able to sell 1,705 livres worth of furs, leaving them unable to repay their debt. The partnership was dissolved on July 19, 1670, with François being released from all responsibility by his mother and brother. Jacques retained ownership of a house at Rivière Saint-Jean that had been given to them. Charlotte and Jacques took on the remaining debt, as well as the unsold merchandise.

Extract from the 1670 list of assets belonging to the dissolved Miville partnership (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

A year before the partnership began, Jacques had already accumulated debt with another merchant. On January 26, 1668, he acknowledged owing Jean Maheu 335 livres for merchandise.

To manage their growing debts, Charlotte and Jacques went before notary Becquet on September 14, 1670, to establish the “constitution of an annual and perpetual annuity” to Alexandre Petit, a merchant from La Rochelle, France. They mortgaged Pierre Miville’s estate, which included a house, barn, and stable. Petit lent them 1,670 livres, to be repaid annually at a rate of 92 livres, 15 sols, and 6 deniers.

Just four days earlier, on September 10, Jacques acknowledged a debt of 171 livres to Bordeaux merchant Jacques de Lamotte for merchandise.

The Miville sons, along with their widowed mother, continued to struggle with debts for years. Charlotte, unable to pay what she owed, was sued by Alexandre Petit. The prévôté of Québec ordered the foreclosure of her land, as well as a house in Québec. François appealed the decision, arguing that half of the land and house belonged to Pierre Miville’s children as part of their inheritance. The Conseil Souverain sided with François.

On November 5, 1674, the Miville children sold their half of the house in Québec’s lower town to notary Gilles Rageot for 150 livres. The next day, an arbitration agreement was drawn up before notary Duquet to resolve the debts of the Miville estate with creditors, namely Charles Bazire and Alexandre Petit. Three arbitrators were appointed to settle the matter and avoid draining the estate’s funds in notarial fees. Both parties agreed to abide by the future arbitration ruling.

The day before, on November 4, 1673, Jacques had transferred a plot of land to Pierre Normand de Labrière. The land measured six arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River. It remains unclear whether any payment was made or what Normand agreed to in exchange for the land.

Ongoing Struggles with Debt

On December 17, 1674, one of the Mivilles' creditors, Charles Bazire, successfully petitioned for François to be appointed curator “for the person and property” of his mother, Charlotte, due to her dementia. François was granted the authority “to pursue or defend the rights of his said mother against whomever it may please.”

Meanwhile, in France, Catherine received a donation from her family, likely alleviating some of the couple’s financial burden. In Paris, on October 11, 1673, Catherine’s mother, Louise de Marle, registered a donation of all her movable and immovable property to her son Antoine. In return, Antoine was required to pay his sister Catherine 600 livres, in settlement of “all rights she may claim in her [mother’s] estate.”

On June 15, 1674, Jacques received a land concession at Rivière Saint-Jean in Grande-Anse from Jean Baptiste Deschamps, sieur de la Bouteillerie. It measured 12 arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River, with “six arpents above and six arpents below the Rivière Saint-Jean,” by 40 arpents deep. Jacques agreed to pay 12 deniers annually in cens, along with two chickens. Less than three weeks later, on July 6, 1674, Jacques transferred half of the concession to Louis Lemieux. In return, Lemieux agreed to pay him 20 sols per arpent of frontage annually, as well as six live capons (or 20 sols each), in addition to the 12 deniers in cens owed to the seigneur of la Bouteillerie. In 1674, the Miville family moved from the côte de Lauzon to Grande-Anse. At the time, many settlers from the Québec City area, Île-d'Orléans, the côte de Beaupré, and Beauport were seeking to establish themselves on the south shore of the St. Lawrence.

The first land concession holders of La Pocatière (Léon Roy, Les terres de la Grande-Anse des Aulnaies et du Port-Joly)

A year later, on July 3, 1675, Jacques received another land concession from Claude de Bermen de la Martinière, acting on behalf of the minor children of Jean de Lauson, the grand seneschal of New France. The deed noted that Jacques was a resident of Grande-Anse. The land concession measured about three arpents and three perches of frontage along the St. Lawrence River, extending forty arpents deep, and was situated next to the land of the late Pierre Miville. The agreement included hunting and fishing rights on the property.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Sep 2024)

According to the terms, Jacques (or someone designated by him) had to settle on the land and begin clearing it within 1675, maintaining continuous improvement. Additionally, he was required to clear and maintain roads, and to have his grains ground at the seigneurie’s mill. On the feast day of Saint-Rémy each year, Jacques had to deliver two live capons, or pay 30 sols each, at the landlord’s discretion, along with 20 sols per arpent of frontage in rente.

Meanwhile, Jacques continued to accumulate debt. On November 19, 1675, he acknowledged owing 150 livres to Delay et Mars, merchants of La Rochelle, for merchandise.

On May 8, 1676, Jacques received a land concession in the seigneurie of “La Bocardière” from Marie Anne Juchereau, the widow of François Pollet de Lacombe. The land measured ten arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River and extended 40 arpents deep, with the Saint-Jean River as a border. Jacques agreed to pay six sols in cash and four live capons as seigneurial rent. Additionally, he was required to grind his grain at the seigneurial mill. (La Bocardière refers to the seigneurie of La Pocatière, which Juchereau had received in 1672; it was also known as Grande-Anse.)

Jacques lost his mother, Charlotte, who had been suffering from dementia, on October 10, 1676. She was buried the following day in “the cemetery of the church on the côte de Lauzon.”

Seven years later, unfinished business remained between Jacques and his French creditors. On June 15, 1677, an agreement was signed between Jacques and Catherine, and Moïse Petit, the son of Alexandre Petit, who was acting on his father’s behalf as a merchant in La Rochelle. Jacques and Catherine transferred all their assets on the côte de Lauzon, including land measuring three arpents and approximately three perches of frontage by 40 arpents deep, to Petit for the modest sum of 150 livres. In turn, Petit was to give part of that sum to Charles Bazire. With this transaction, Jacques’s debts to both Petit and Bazire were finally settled.

Later that year, on September 1, Jacques purchased a land concession at Rivière-Ouelle from Jacques Bernier dit Jeandeparis for 40 livres. The land measured six arpents of frontage, facing the Ouelle River, by twelve arpents deep. The annual rente on the property was 60 sols and three capons (or 20 sols each).

In 1681, a census was conducted in New France. Jacques and Catherine were recorded living in Rivière-Ouelle with their four children. The family owned two guns, seven head of cattle, and had eight arpents of land under cultivation.

1681 census for the household of Jacques Miville (Library and Archives Canada)

The Tragic Deaths of Jacques and Catherine

Jacques Miville dit Deschênes died on January 27, 1688, at the age of 48. He was buried the next day in the parish of Notre-Dame-de-Liesse in Rivière-Ouelle. Catherine de Baillon was buried two days later, on January 30, 1688, also in Rivière-Ouelle, though her burial record does not include a date of death. The couple likely succumbed to the smallpox epidemic that devastated the colony that year.

1688 burials of Jacques Miville dit Deschênes and Catherine de Baillon (Généalogie Québec)

The sudden deaths of Jacques and Catherine left five children orphaned, likely in a precarious financial situation. Jacques’s brother, François, became the children’s legal guardian. This arrangement was officially dissolved by a notarial deed on September 15, 1698, by which time all the children had reached adulthood.

Over the centuries, the descendants of Jacques and Catherine spread across Québec, Canada, and the United States, now numbering in the thousands. The Miville family played a role in the development of New France and left a lasting mark on the genealogical history of North America. Their story continues to be significant for those tracing their ancestry back to a noblewoman from France and a Swiss settler.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

"Hiers-Brouage, Collection communale, Baptêmes Mariages Sépultures, 1620-1650," digital images, Archives de la Charente-Maritime (http://www.archinoe.net/v2/ark:/18812/3badb75b77f105ba04222d4d16bdd4b7 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), baptism of Jacques Miville, 2 May 1639, image 96 of 176.

"Département des Manuscrits, Français 31109," digital images, Bibliothèque nationale de France (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10080195g : accessed 19 May 2020), Cabinet de d'Hozier vol. 228, no. 5952, folio 39.

"Châtelet de Paris, Y//226-Y//230, Insinuations (1673-1676)," Archives nationales (https://francearchives.fr/fr/facomponent/35637ff94456aaafea70af840e903df9f7197c06 : accessed 19 May 2020), notice 679, folio 287.

"Fonds Conseil souverain - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/398336 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Concession par Alexandre de Prouville, chevalier, seigneur de Tracy, conseiller du Roi en Ses conseils, lieutenant général pour Sa Majesté en l'Amérique méridionale et septentrionale, tant par mer que par terre, à Pierre Miville, François Rimé, François Miville, Jacques Miville, François Tisseau, Jean Gueuchard et Jean Cahusin, tous Suisses, d'une terre située au lieu nommé la Grande-Anse, sise quinze lieues au-dessous de Québec en allant vers Tadoussac, du côté du sud," 16 Jul 1665, reference TP1,S36,P38, ID 398336; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre des insinuations du Conseil supérieur de Québec établi en Canada par l'Édit du Roi Louis XIV du mois d'avril 1663 (28 décembre 1628 au 1er mai 1682), volume A, f. 14. Publiée dans le Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, volume XX, p. 233. Pour consulter les pages du registre permettant de comprendre son contexte de création, sa valeur juridique et administrative, son contenu ou l'historique de sa conservation, voir les pièces TP1,S36,PAA et TP1,S36,PKK.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/398760 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Procès de Jacques Bigeon, environ 50 ans, cordier (celui qui fabrique ou qui vend des cordes), natif de La Flotte à l'île de Ré, paroisse de Sainte-Catherine, accusé du meurtre de Nicolas Bernard," 28 Jan 1668 to 26 Apr 1668, reference TP1,S777,D109, ID 398760; citing original data : Dossier provenant du registre Procédures judiciaires Matières criminelles, tome I : 1665-1696, f. 46-86b. Pour les arrêts prononcés sur cette cause par le Conseil souverain de Québec, les 23 et 26 avril 1668, voir les pièces TP1,S28,P575; TP1,S28,P577.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/400753 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Appel mis au néant de la sentence rendue par le lieutenant général, en date du 2 septembre 1672, entre les héritiers du défunt Pierre Miville et Moïse Petit, marchand et procureur d'Alexandre Petit et correction de la dite sentence," 2 May 1673, reference TP1,S28,P817, ID 400753 ; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre no 1 des arrêts, jugements et délibérations du Conseil souverain de la Nouvelle-France (18 septembre 1663 au 19 décembre 1676), f. 169v-170.

Ibid. (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/401112 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), "Nomination de François Miville comme curateur à la personne et aux biens de Charlotte Mongis, sa mère, veuve de feu Pierre Miville, vu qu'elle est démente, sur la requête de Charles Bazire, agent de la Compagnie des Indes occidentales et Moïse Petit, procureur d'Alexandre Petit, marchand," 17 Dec 1674, reference TP1,S28,P1023, ID 401112; citing original data : Pièce provenant du Registre no 1 des arrêts, jugements et délibérations du Conseil souverain de la Nouvelle-France (18 septembre 1663 au 19 décembre 1676), f. 215.

“Actes de notaire, 1663-1687 : Pierre Duquet,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YBWT?i=1145&cat=1175224 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), marriage contract of Jacques Miville Deschesnes and Catherine de Baillon, 19 Oct 1669, images 1146-1149 of 2541; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YBS9?cat=1175224 : accessed 22 Aug 2024), work contract between Jacques Miville Deschesnes and Raymond Cornut and Jean Boudeau, 21 Oct 1669, images 1154-1155 of 2541.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YB2Z?cat=1175224&i=1310 : accessed 10 Sep 2024), donation to the Confrérie de Sainte-Anne by Charlotte Maugis, François Miville and Jacques Miville Deschesnes, 18 Jul 1670, images 1311 to 1313 of 2541.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-YBMV?cat=1175224&i=2009 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), transaction between Charles Bazire, Alexandre Petit and François Miville, 6 Nov 1674, images 2010 to 2011 of 2541.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-Y9C3-1?cat=1175224&i=1902 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), concession by Jacques Miville to Louis Lemieux, 6 Jul 1674, images 1903 to 1904 of 2541.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-Y9SL-3?cat=1175224&i=2347 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), obligation of Jacques Miville to Defay et Mars, 19 Nov 1675, image 2348 of 2541.

“Actes de notaire, 1666-1691 : Gilles Rageot,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVF-YQHL-Q?cat=1171570&i=761 : accessed 6 Sep 2024), work contract between Jacques Miville Deschesnes and Jean Cazenave, 10 Apr 1670, image 762 of 1443.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSVF-YQCX-J?cat=1171570&i=362 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), obligation from Jacques Miville to Jean Maheut, 26 Jan 1668, images 363 to 364 of 1443.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZN1?cat=1171570&i=887 : accessed 6 Sep 2024), land transfer from Jacques Miville Deschesne to Pierre Normand de Labrière, 4 Nov 1674, image 888 of 3381.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZVN?cat=1171570&i=1392 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), land concession ticket from the sieur de la Bouteillerie to Jacques Miville, 15 Jun 1674, image 1393 of 3381.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZ54?cat=1171570&i=1391 : accessed 11 Sep 2024), agreement between Moïse Petit and Jacques Miville and Catherine Baillon, 15 Jun 1674, images 1392 to 1396 of 3381.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3DQ-JZ4Q?cat=1171570&i=1472 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), sale of land from Jacques Bernier dit Jeandeparis to Jacques Miville Deschesnes, 1 Sep 1977, images 1473 to 1474 of 3381.

“Actes de notaire, 1665-1682 : Romain Becquet,” digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=KXmcijcIBp8tUjPuu5T-wg : accessed 10 Sep 2024), dissolution of partnership between Charlotte Montgy, François Minville and Jacques Miville-Deschesne, 19 Jul 1670, images 423 to 426 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=d3DdpHOWmEpR2KpUCSkiVQ : accessed 10 Sep 2024), constitution of an annual and perpetual annuity by Charlotte Montgy and Jacques Miville-Deschesne to Daniel Biaille de St Meru in the name of and as proxy for Alexandre Petit, 14 Sep 1670, images 806 to 808 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064890?docref=oqP9Uz4L-pg8HLIoYKoaHw : accessed 11 Sep 2024), obligation of Jacques Miville-Deschesne to Jacques de Lamotte, 10 Sep 1670, image 804 of 921.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064892?docref=IW-zaQy29lm34r9GNdP9yg : accessed 10 Sep 2024), sale of half a house in Québec by François Miville (and his siblings) to Gilles Rageot, 5 Nov 1674, images 734 and 735 of 954.

Ibid. (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4064893?docref=X-mrZ4YpQIxbP19E4ClQ-w : accessed 11 Sep 2024), land concession to Jacques Miville-Deschesne, 8 May 1676, images 198 to 200 of 1117.

“Actes de notaire, 1674-1680 : Claude Maugue,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-RSDN-P?cat=964088&i=3119 : accessed 30 Sep 2024), land concession to Jacques Minville-Deschene, 3 Jul 1675, images 3120 to 3121 of 3165.

“Actes de notaire, 1696-1716 : Louis Chambalon,” digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-P3NF-HSW9?cat=1170051&i=1062 : accessed 30 Sep 2024), withdrawal of guardianship by François Miville of the children of the deceased Jacques Miville and Catherine-Marie Baillon, 15 Sep 1698, image 1063 of 3419.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), entry for Pierre Miville, 1667, Côte de Lauzon, Finding aid no. MSS0446, item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), entry for Jacques Miville, La Bouteillerie, 14 Nov 1681, finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69063 : accessed 6 Sep 2024), burial of Pierre Miville dit Le Suisse, 15 Oct 1669, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/66896 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), marriage of Jacques Miville and Catherine Baillon, 12 Nov 1669, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/69280 : accessed 12 Sep 2024), burial of Charlotte Mongis, 11 Oct 1676, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/17157 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), burial of Jacques Minville, 28 Jan 1688, Rivière-Ouelle (Notre-Dame-de-Liesse).

[1] Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/17158 : accessed 13 Sep 2024), burial of Marie Catherine Bayon, 30 Jan 1688, Rivière-Ouelle (Notre-Dame-de-Liesse).

Rene Jetté, John P. DuLong, Roland-Yves Gagne and Gail F. Moreau, "From Catherine Baillon to Charlemagne," American-Canadian Genealogist, Issue 82. Volume 25. Number 4, 1999 (https://acgs.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ACGS_Baillon_1999.pdf : accessed 19 May 2020); citing Archives Nationales, Insinuations aux Châtelet de Paris, Y 227, fo. 287, 25 October 1673.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) online database (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/5146 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), dictionary entry for Marie Catherine Baillon (person 5146).

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd.com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/86413 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), dictionary entry for Jacques MIVILLE DESCHENES and Marie Catherine BAILLON.

Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie, Fichier Origine online database (https://www.fichierorigine.com/recherche?numero=240172 : accessed 20 Aug 2024), entry for Catherine (de) Baillon (person #240172), updated 29 Nov 2023.

René Jetté and the PRDH, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec des origines à 1730 (Montréal, Gaëtan Morin Éditeur, 1944), page 817, entry for Catherine (de) Baillon.

Yves Landry, Orphelines en France, pionnières au Canada: Les Filles du roi au XVIIe siècle (Montréal, Leméac Éditeur, 1992), 297.

Peter Gagné, Kings Daughters & Founding Mothers: the Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, Volume One (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2001), 176-177.

Raymond Ouimet and Nicole Mauger, “Catherine de Baillon : une exclue?," L’Ancêtre, Société de généalogie de Québec, volume 29-N01, autumn 2002, 23-30.

Thomas J. Laforest, Our French-Canadian Ancestors vol. 27 (Palm Harbor, Florida, The LISI Press, 1998), 108, 120-121.