Ludwig "Louis" Demuth & Marie Blanchet

Discover the remarkable story of how a former Hessian soldier who fought in the American Revolution and a Canadian-born farmer’s daughter built a life together in Québec City after the war. Ludwig “Louis” Demuth, a drummer in the von Loßberg Regiment, deserted his post and chose to settle in Canada. Their journey is one of transformation, resilience, and adaptation, taking them from the battlefields of revolutionary America to the vibrant streets of Québec, where Louis established himself as a successful merchant.

From Soldier to Settler: The Story of Ludwig "Louis" Demuth & Marie Blanchet

This is the remarkable story of how a former Hessian soldier who fought in the American Revolution and a Canadian-born farmer’s daughter built a life together in Québec City after the war. Ludwig “Louis” Demuth, a drummer in the von Loßberg Regiment, deserted his post and chose to settle in Canada. Their journey is one of transformation, resilience, and adaptation, taking them from the battlefields of revolutionary America to the vibrant streets of Québec, where Louis established himself as a successful merchant.

Ludwig Demuth was born around 1756 in Rinteln, a town in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, a principality within the Holy Roman Empire. The names of his parents are not known. Hesse-Kassel, ruled by the influential House of Hesse, was a small but strategically significant state in early modern Germany. Rinteln, an important town within the principality, was known for hosting the Protestant Alma Ernestina university, which operated from 1621 until its closure in 1810. Today, Rinteln is part of the German state of Lower Saxony and has a population of approximately 26,000 as of 2023.

Rinteln, 1647, illustration by Matthäus Merian (Wikimedia Commons)

Rinteln, 2008 (photo by Franzfoto, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The 13th-century Jakobikirche in Rinteln (photo by Tilman2007, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

During Ludwig’s youth, what is now Germany was not a unified nation but rather a patchwork of several hundred semi-autonomous states. These included kingdoms, duchies, archduchies, counties, electorates, bishoprics, free cities, and small seigneuries. Although these states were nominally under the rule of Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II of the Habsburg monarchy, they differed greatly in language, religion, political priorities, and socio-economic conditions.

Each state maintained its own army, a reflection of the fragmented political landscape. In the conflict-prone 18th century, these armies were often highly trained, and most states mandated military service for their male residents from an early age. The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel was no exception, requiring registration at the age of 7 and service between the ages of 16 and 30, as needed.

Maintaining a professional military was costly, and Hesse-Kassel became infamous for offsetting these expenses by hiring out its soldiers as auxiliaries to foreign armies. Despite serving alongside foreign forces, Hessian troops fought under their own flag, wore their own uniforms, and were led by their own officers, preserving their distinct identity on the battlefield.

Map of the Holy Roman Empire in 1789, showing the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (map by Robert Alfers ziegelbrenner, Wikimedia Commons)

At around 18 years of age, Ludwig was recorded in the Hessische Truppen (Hessian Troops) for the first time. In April 1775, he was assigned as a drummer to Company 3 of the von Loßberg Regiment. That year, 38 other men from Rinteln also joined the Hessian military. It is estimated that one in four able-bodied men in Hesse were pressed into service during this period, reflecting the state's heavy reliance on conscription to maintain its armed forces.

The von Loßberg Regiment, originally known as the Schaumburg Regiment, was established in 1683. It had a long history of military campaigns, participating in conflicts such as the War of the Spanish Netherlands, the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of the Polish Succession, the War of the Austrian Succession, and the Seven Years' War. By the time Ludwig enlisted, the regiment was headquartered in Rinteln and commanded by Major General Heinrich August von Loßberg.

German Soldiers in the American Revolution

In 1776, as the American Revolutionary War began, Great Britain’s King George III sought additional manpower to suppress the colonial rebellion. To meet this need, he negotiated agreements with six German territories within the Holy Roman Empire to supply soldiers. Among these, Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, leased several military units, including the von Loßberg Regiment, in exchange for substantial financial compensation—reportedly equivalent to thirteen years’ worth of the state’s tax revenue.

Because a large number of these troops came from Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau, German soldiers serving in America were collectively referred to as “Hessians.” Nearly 30,000 German soldiers fought alongside the British during the American Revolution, comprising a significant portion of the British military effort in the colonies.

Fusilier Regiment of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel between 1783 and 1789 (Georg Ortenburg, Landesgeschichtliche Informationssystem Hessen)

“The uniforms of the von Lossberg Regiment differed somewhat from those worn by most of the other units in the Hessian contingent. Like the others, they wore tri-cornered hats with pom-poms, their coats were long with turned back skirts, the vests were belted, and the breeches tight and fitted into boots. However, where the color of the coats of most of the other Hessian regiments were blue with varying colored lapels, cuffs, facing and trim, the coats of the Lossbergs were scarlet.

Like the other German regiments, the Lossbergs had their own distinctive colors, or flags, which they carried into battle. On their banner were the words, ‘Pro Principe et Patria,’ a motto perhaps somewhat incongruous for the mission they were about to undertake.”

Ludwig and the von Loßberg Regiment were part of the first wave of Hessian troops sent to America. In March 1776, five companies of the regiment marched north along the Weser River from Rinteln to Lehe (now Bremerhaven), their port of embarkation. The journey covered nearly 200 kilometres and took about a week to complete.

At Lehe, Ludwig boarded one of four British troop transports—the Union, Charming Polly, Mary, or Judith. These transports formed part of a 54-vessel fleet that departed on April 17 and arrived in Portsmouth, England, ten days later. There, the fleet collected additional troops and gained an escort of British warships. By the time it set sail for America on May 6, the fleet had grown to 150 vessels, carrying 12,500 troops, including 7,400 German auxiliaries.

The transatlantic voyage was grueling and fraught with hardships. Storms scattered the fleet across the ocean, and provisions quickly became unfit for consumption. The sea biscuits were infested with maggots, the pork and beans spoiled, and the drinking water turned foul. Berths were overcrowded and fetid, making the journey nearly unbearable for the soldiers on board.

“Landing of British Troops in New York, 1776,” engraving (National Army Museum)

After weeks at sea, the sight of Newfoundland on June 20 lifted spirits briefly, but the men soon discovered they were still far from their destination of Halifax. The prolonged journey only worsened morale, and upon arriving in Halifax, the soldiers were met with further disappointment: they were ordered to continue on to New York.

The von Loßberg Regiment finally reached New York Harbor on the morning of August 12, 1776, anchoring off Staten Island after nearly four months of travel.

The Battle of Long Island

In New York, Ludwig and the von Loßberg Regiment took part in General William Howe's campaign to seize control of the city and its surrounding areas, including Long Island, from George Washington and the Continental Army. Howe commanded a formidable force of 20,000 troops, outnumbering the 10,000 soldiers of the Continental Army.

On August 27, 1776, Howe executed a carefully planned flanking maneuver on Long Island. His forces marched through the lightly defended Jamaica Pass, successfully outflanking the American troops positioned on Brooklyn Heights. Taken by surprise, the Continental soldiers were thrown into disarray and attempted a hasty retreat. The British and Hessian forces inflicted approximately 1,000 casualties and captured a similar number of American prisoners.

“Battle of Long Island” (History Department, United States Military Academy)

The Battle of Long Island marked a sobering defeat for the Continental Army. Forced to evacuate across the East River to Manhattan, they left behind valuable supplies, including guns, ammunition, horses, and cattle. According to one account, an American officer reportedly declared that "against such an enemy as the Hessians, resistance was impossible, and there was nothing to do but retreat."

“Lord Stirling leading an attack against the British in order to buy time for other troops to retreat at the Battle of Long Island, 1776,” 1858 engraving by Alonzo Chappel (Brooklyn Historical Society)

“Retreat from Long Island [N.Y.], Aug. 29, 1776,” engraving by John McNevin (Library of Congress)

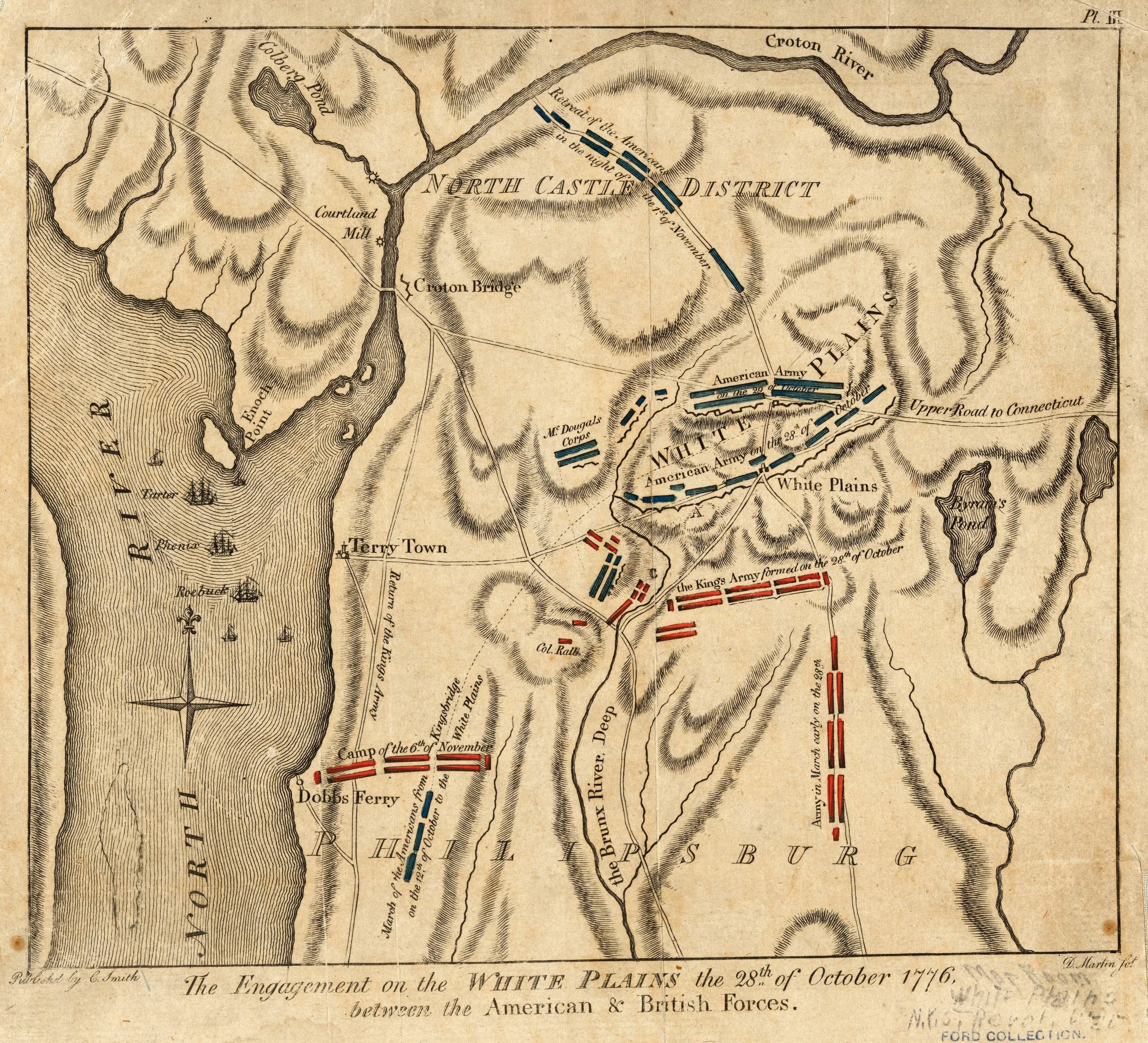

The Battle of White Plains

After their retreat from Long Island, General George Washington and the Continental Army moved north to regroup. Determined to keep the pressure on, General William Howe pursued them. On October 28, 1776, Howe launched another flanking maneuver, forcing Washington into a defensive position on the high ground near White Plains.

The von Loßberg Regiment played a key role in the British frontal assault on Chatterton Hill, a critical position in the American defensive line. The Hessians’ advance shattered Washington's right flank, breaking through the Patriot lines and securing control of the hill. With White Plains lost, Washington was forced to retreat yet again, leading his troops further north and abandoning New York City to the British.

“The engagement on the White Plains, the 28th of October 1776 : between the American & British forces,” 1796 engraving by D. Martin (New York Public Library Digital Collection)

The Battle of Fort Washington

After his victories at Long Island and White Plains, General William Howe turned his attention to Fort Washington, a strategic Continental Army stronghold located at the northwestern tip of Manhattan. Although George Washington recommended abandoning the fort, its commander, Colonel Robert Magaw, was confident his forces could hold their position.

“A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel Redouts near New York on the 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades,” 1776 painting by Thomas Davies (New York Public Library)

On November 16, 1776, approximately 8,000 British and Hessian troops launched a coordinated assault on the fort. The von Loßberg Regiment participated in the northern attack, pressing against the fort’s defenses. Outnumbered and overwhelmed, Colonel Magaw was eventually forced to surrender. The British captured Fort Washington along with approximately 2,900 Continental soldiers, securing their control of Manhattan Island.

However, this victory marked the high point of the German troops’ involvement in the American Revolution. Disaster loomed barely a month away—a catastrophe in which the von Loßberg Regiment would play a pivotal role.

“Attacks of Fort Washington by His Majesty's forces: under the command of Genl. Sir Willm Howe K.B.,” 1861 map by George Hayward (New York Public Library)

The Battle of Trenton

Battle of Trenton (History Department, United States Military Academy)

Following a series of defeats, the Continental Army retreated across New Jersey, eventually crossing the Delaware River to gain a defensive advantage before bivouacking around McConkey's Ferry, Pennsylvania. There, with improvised quarters, short rations, and a depleted army, morale was at a low. In a bold effort to shift the tide of the war, George Washington devised a surprise attack on the Hessian garrison stationed in Trenton, New Jersey. The garrison, led by Colonel Johann Rall, consisted of 1,400 to 1,500 troops from three regiments: the von Loßberg Regiment, the von Knyphausen Regiment, and the Rall Regiment. Rall mistakenly assumed that fighting would not resume until spring unless the Delaware River froze solid.

On Christmas night, 1776, Washington and his 2,400 men famously crossed the icy Delaware River and marched ten miles southeast in freezing conditions to launch a pre-dawn assault on Trenton The Hessians, caught completely off guard, struggled to organize a defense as the battle spilled into the streets of the town. The Continental Army achieved a decisive victory, killing 22 Hessians, wounding 92, and capturing 918. About 400 Hessians evaded capture, including an estimated 140 men from the von Loßberg Regiment. The Americans also seized much-needed supplies, including weapons, ammunition, and horses. The victory at Trenton marked a turning point in the war, revitalizing support for Washington and the revolutionary cause.

While hundreds of Hessian prisoners were marched to Philadelphia and Virginia, Ludwig Demuth likely managed to escape. Records suggest that approximately 20 British and Hessian musicians and drummers fled Trenton during the chaos of the battle.

After the Battle of Trenton, the Hessian soldiers who evaded capture regrouped and retreated toward British-controlled territory. They traveled north to Princeton, where they joined British forces stationed there. From Princeton, the retreat continued to New Brunswick, New Jersey, before the survivors eventually reunited with the main British army in New York. The von Loßberg Regiment arrived in New York on July 6, 1777. Approximately three weeks later, it was officially reestablished as part of the Loos Brigade, allowing the regiment to regain its operational strength.

Once in New York, the escaped Hessians, including remnants of the von Loßberg Regiment, were reorganized and reinforced by additional German troops arriving from overseas. New York City, the primary British stronghold and logistical hub during the war, became their base of operations.

In May 1778, Hessian troops in America learned that France was preparing to declare war on England, an event that would escalate the Revolutionary War into a broader international conflict. Four months later, in September, the von Loßberg Regiment, the von Knyphausen Regiment, and the British 44th Regiment were ordered to transfer to Canada. All three regiments were under the command of Colonel von Loos. At the time of departure, the von Loßberg contingent included 576 people, comprising officers, surgeons, musicians, servants, women, and children.

Regiment of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Cassel until 1786 (Landesgeschichtliche Informationssystem Hessen)

The ships departed from New York Harbor on the morning of September 9, but a violent storm disrupted the voyage. The battered fleet attempted to return to New York for repairs, and one vessel, the Adamant, is believed to have been lost in the storm. While a few ships were captured during the ordeal, most made it back to port safely. Ludwig appeared on his regiment's roll call in New York in October 1778. The von Loßberg Regiment overwintered in New York City, awaiting further orders.

The troops finally set sail again on May 17, 1779, and arrived at the port of Québec on May 25. Shortly after their arrival, the regiment was stationed in nearby Beauport. In June 1779, just one month later, Ludwig was promoted to the rank of fusilier.

In August 1779, several units, including the von Loßberg Regiment, were relocated to a camp on the Plains of Abraham. Their primary responsibilities included defending Québec from the west and constructing new fortifications to strengthen the city’s defenses. In November, the regiment was ordered to sail to Île-d’Orléans for the winter and was stationed in the village of Saint-Pierre. The soldiers, unaccustomed to the harsh Canadian winters, were poorly dressed, with many using their hard-earned wages to buy fur hats. Eventually, proper winter clothing, wool blankets, and snowshoes were distributed to the men.

“Hessian Private, Erb Prinz Fusileer Regiment of Hesse-Cassel,” drawing by Charles MacKubin Lefferts (The New York Historical Society)

By the summer of 1781, the von Loßberg Regiment, the von Knyphausen Regiment, and the British 31st and 44th Regiments were consolidated into a single battalion stationed just west of Québec. The combined forces continued to work on fortifying the city’s defenses. During the bitterly cold winter of 1781–1782, the von Loßberg Regiment was assigned to overwinter in several south shore villages, including Saint-Thomas, Saint-François, Saint-Pierre, and Berthier. The following summer was again spent working on Québec’s fortifications.

In the winter of 1782–1783, the von Loßberg Regiment was stationed in the villages of Saint-Thomas, Cap-Saint-Ignace, and L’Islet, also located on the south shore of the St. Lawrence.

On April 28, 1783, news reached Halifax from Europe: the war was over. By May, orders were issued for all German troops to return to Europe. For many soldiers, the announcement brought joy and anticipation at the prospect of returning home. However, others, like Ludwig, faced conflicting emotions, having spent four years in Québec and forged connections with local communities. Perhaps as an incentive to return, Ludwig was promoted to the rank of private in June 1783.

General von Loos received the following letter from General Frederic Haldiman, the Governor of the Province of Québec, dated August 2, 1783:

Sir:

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter and the attached certificates of the regimental commanders of the various National troops under your command. I have thereby been assured that your brigade has no complaints with the treatment your troops have experienced under my command. I ask you, Sir, to inform your officers that it has always been my desire to make you and your troops as comfortable as the nature of our duties would permit. I am gratified to learn that you are satisfied with my efforts in your behalf.

Permit me, Sir, to also express on this occasion my complete satisfaction with the ardour and attention which you have demonstrated while in the king's service and with the excellent condition and discipline of the troops under your command.

I have the honor, Sir, to be with the greatest respect

Your most obedient servant,

Frederic Haldimand

On the evening of August 2, 1783, a total of 303 German passengers boarded ships docked at Pointe-Lévy to begin their return journey across the Atlantic. In the week leading up to embarkation, hundreds of Hessian soldiers deserted, including 17 men from the von Loßberg Regiment. Ludwig Demuth was among those who did not board when the ships set sail four days later.

Of the 394 von Loßberg troops who departed Rinteln in 1776, only 84 returned to Germany seven years later. On a larger scale, of the nearly 30,000 German soldiers sent to fight alongside the British in North America, approximately 17,000 are believed to have returned home after the war.

Forging a New Life: Ludwig Demuth’s Path from Soldier to Settler

Following his desertion, Ludwig Demuth settled in the Québec City area, where he began a new life as a merchant. He frequently used the given name “Louis” or “Lewis,” likely adapting to his audience's linguistic and cultural preferences. The first recorded mention of him in Canada’s public records dates to January 30, 1787, when he served as a witness at the wedding of Henry Baacke [Heinrich Bock] and Marie Anne Pouliot at the Anglican Metropolitan Church in Québec City. Another witness was William [Wilhelm] Meyer, identified as a “foreman in the Engineers.”

Signature portion of the 1792 property purchase, showing Louis’s signature (FamilySearch)

Heinrich Bock, like Ludwig, was a former German soldier, having served with the Brunswick Regiment from Braunschweig (also known as Brunswick), a contingent of German troops allied with the British during the Revolutionary War. Heinrich is also the 'Henry Baker' listed alongside Ludwig on the 1799 land petition, which is discussed later.

On October 9, 1792, Louis’s name appeared for the first time in an existing notarial record. On that date, he purchased a property in Québec’s Faubourg Saint-Jean from Joseph Blouin for 800 livres and 20 sols. The record noted Louis as a resident of the same faubourg, living on rue Saint-George. The newly acquired property, also located on rue Saint-George, measured 40 feet wide by 60 feet deep and included a wooden house built on a stone foundation. Notably, Louis already owned the adjacent property to the northeast.

Marie Blanchet

The village of Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud, 1884 drawing by François-Xavier Paquet (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

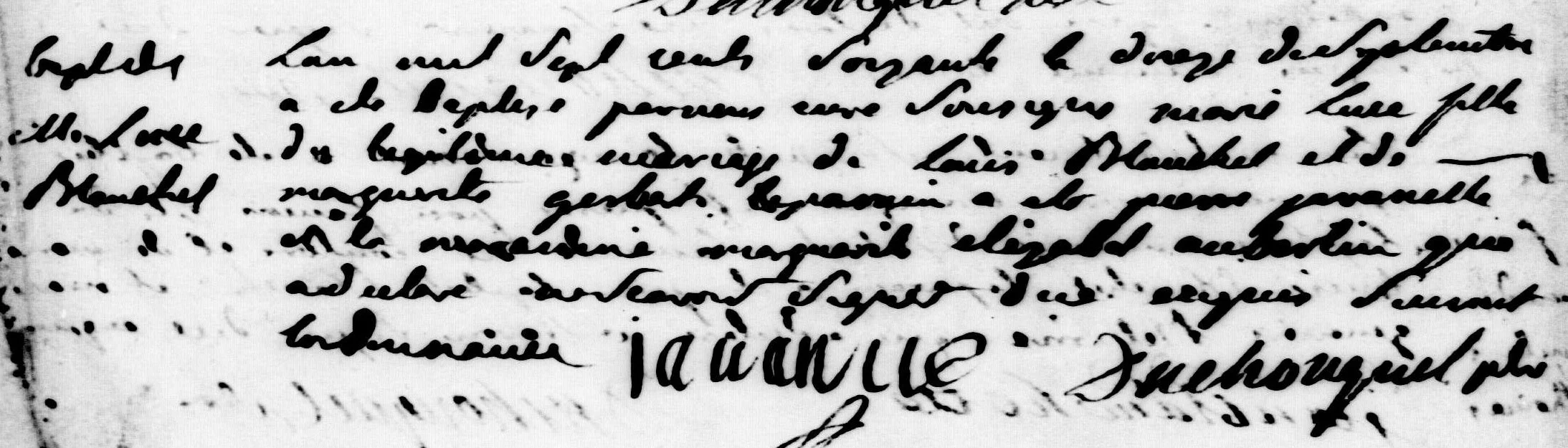

Marie Blanchet, the daughter of Louis Blanchet and Marie Marguerite Gerbert (or Jalbert), was baptized “Marie Luce” on September 12, 1760, in Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud, in Canada. At the time, Canada was part of the French colony of New France. Despite her baptismal name, she appears not to have used it in daily life. Her godparents were Pierre Javanelle and Marguerite Aubertin.

Marie grew up in Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud, alongside her eleven siblings, though one sister died in infancy. Her father, Louis Blanchet, worked as a “cultivateur,” or farmer.

1760 baptism of Marie Blanchet (Généalogie Québec)

During the winter of 1781–1782, British and German troops, including Hessians, overwintered in Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud. At the time, Marie was 21 or 22 years old. It was likely during this period that she met her future husband, Louis Demuth.

The Marriage of a Hessian Soldier and a Canadian Farmer’s Daughter

On June 2, 1794, “Lewis Damut” married “Mary Blanchette” in the Anglican Metropolitan parish of Québec. Louis was recorded as both a merchant and possibly a “musician,” perhaps referencing his earlier role as a drummer during his time in the military. Witnesses to the wedding included Marie’s brother, Pascal Blanchette, and Lawrence Gordon, a carter.

1794 Marriage of Louis and Marie (Généalogie Québec)

Québec’s Anglican Church

The Church and Monastery of the Récollets was a group of religious buildings and gardens adjacent to Place d'Armes, in Québec. Construction began in 1671 and continued until 1692. During the siege of Québec in August 1759, which preceded the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, the buildings sustained significant damage. After the Conquest in 1760, the British regime prohibited new recruitment to the Récollets religious order, forcing the community to evacuate the site. The chapel was repaired and temporarily repurposed as a Protestant church. However, it also served the Catholic community, as many Catholic churches in the city had been destroyed and would not be repaired for several years. The church and monastery were ultimately destroyed by fire in 1796.

The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, the seat of the Anglican Diocese of Québec, was established in 1793. Construction of the cathedral began in 1800 and was completed in 1804. On August 28, 1804, it was consecrated, becoming the first Anglican cathedral built outside the British Isles.

“View of the Cathedral, Jesuits College, and Recollect Friars Church, Quebec City,” 1761 print by Richard Short (Wikimedia Commons)

Louis and Marie settled in Québec City. Although they were married in a Protestant ceremony, they chose to baptize all six of their children in the Catholic faith:

Marie Josèphe (1795–1795)

Louis (1796–1869)

Marie Louise (1797–1862)

Julie (1799–1882)

Édouard (1800-1801)

Marguerite (1802–1866)

Between 1799 and 1802, Louis submitted three petitions for land in Lower Canada (modern-day Québec). These land grants were intended for “subalterns, non-commissioned officers and privates, who have served during the late American War in that and other German Corps and being discharged at the peace in 1783 have remained in this province.” The petitions requested “a small proportion of the Waste Lands of the Crown as a Mark of the Approbation of [Government?] for their past services.” It is unlikely that Louis was ever granted any land, as there is no record of him owning rural property or being involved in rural land sales. Instead, he appears to have remained in Québec City for the rest of his life, focusing on his urban life and work.

Extract of 1799 land petition for the Hesse-Cassel troops (Library and Archives Canada)

Louis’s Business Endeavours

Louis was a highly active merchant in Québec City, with his name appearing in 101 notarial documents between 1792 and 1817. These records provide insight into his extensive involvement in real estate and financial dealings:

45 sales: Numerous property transactions, primarily involving properties in the Faubourg Saint-Jean area.

26 obligations (debts): Financial agreements documenting debts owed to or by Louis.

13 receipts: Records of payments or settlements involving various individuals.

11 leases: Rental agreements, suggesting Louis managed or leased his properties.

3 exchanges: Land swaps, often involving properties on rue Saint-George.

3 arrangements: Formal agreements, likely resolving disputes or finalizing transactions.

Other activities: Smaller transactions, including concessions, retrocessions, and land transfers, further illustrate Louis's active role in Québec's business community.

Although primarily documented as a merchant, Louis is referred to as a “master innkeeper” in 1804 and 1807, possibly indicating a temporary shift or additional venture. His residence was consistently recorded in Faubourg Saint-Jean, often specifically on rue Saint-George (now Côte d’Abraham, as renamed in 1890).

Map of Quebec City and the suburbs of St-Jean-Baptiste and Saint-Roch, circa 1814 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Close-up of the Map of Quebec City and the suburbs of St-Jean-Baptiste and Saint-Roch, circa 1814, highlighting rue Saint-George (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Quebec Gazette | La gazette de Québec, March 29, 1804 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

On March 5, 1804, Louis received a “Certificat de vie et mœurs," or certificate of good conduct, from the courts in Québec City, a formal document attesting to his character and reputation. This certificate was a prerequisite for him to operate as an innkeeper.

Louis was not only a successful merchant but also an active member of his community. In 1804, he served on the Fire Society committee, an organization dedicated to preventing fire-related accidents in Québec City.

A Brush with the Law

Despite their standing in the community, Louis and Marie were not always law-abiding citizens. An article published in an 1805 newspaper reports that the couple was found guilty of being accessories to burglary and subsequently sentenced to prison. This incident stands in stark contrast to Louis’s otherwise prominent role as a merchant. The charge of being accessories “after the fact” suggests they may have either knowingly or unknowingly provided lodging to the burglars at the Demuth inn or sold stolen goods through Demuth’s shop.

The Quebec Gazette | La gazette de Québec, September 5, 1805 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Death of Marie Blanchet

Marie Blanchet died at the age of 47 on October 18, 1807. She was buried the following day in the “cimetière des picotés” in Québec City. Her husband, Louis, was recorded as an “aubergiste,” or innkeeper, in her burial record.

1807 burial of Marie Blanchet (Généalogie Québec)

The Cimetière des picotés

Our ancestors experienced numerous epidemics and pandemics, including outbreaks of influenza, cholera, smallpox, and typhus. These public health crises often overwhelmed local cemeteries, which lacked sufficient space for the victims of widespread disease. When possible, separate sections of existing cemeteries were used for mass burials. In cases of extreme overcrowding, new burial grounds were hastily established.

In Québec City, a severe influenza outbreak in 1700–1701 led to the creation of a new cemetery near the Hôtel-Dieu, at the corner of Hamel and Couillard Streets. Just a few years later, during the smallpox epidemic of 1702–1703, many victims were interred there, earning the burial ground its nickname, cimetière des picotés (loosely translated as "cemetery for the poxed"). Over time, the cemetery remained in use for epidemic victims, but concerns about hygiene and odours eventually led to its closure in 1857. Learn more about burial places here.

A New Chapter: Louis and Pélagie Dauphin

“Ste. Anne Street,” with a view of Saint-Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Québec, circa 1830 watercolour by James Pattison Cockburn (Royal Ontario Museum)

Dedicated in 1810, the church remains relatively unchanged except for the Vestry addition in 1900.

In the summer of 1815, Louis was enumerated in the parish census of Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Recorded as a 60-year-old merchant, he owned a home on the north side of rue Saint-George. The census described Louis as the widower of Marie Blanchet and the unmarried partner of Pélagie Dauphin. Notably, Pélagie had been the godmother of Louis’s daughter Marguerite, baptized in 1802.

Later that year, on November 25, 1815, Louis and Pélagie were married at Saint Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Québec. Louis was approximately 59 years old at the time, while Pélagie was a 39-year-old widow of Claude Morand (or Morin). Together, the couple had two children: Luce, born out of wedlock in 1812, and Henri, born in 1817.

1815 marriage of Louis and Pélagie (Généalogie Québec)

Saint-Andrew’s Presbyterian Church (©2022 photo by The French-Canadian Genealogist)

In 1818, Louis and his family were listed in the parish census of Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Curiously, he was again recorded as a 60-year-old merchant, the same age noted in the 1815 census, as though he had not aged in three years. The census described Louis as the widower of Marie Blanchet. His wife, Pélagie Dauphin, was included in the household, along with their children: Louis Jr., Marie Louise, Julie, Marguerite, Luce, and Henri. There was one Protestant living in the household (Louis) and five Catholics (his wife and oldest children).

1818 census for the parish of Notre-Dame-de-Québec (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Death of Ludwig “Louis” Demuth

Louis Demuth passed away on February 21, 1820, at the age of about 64. He was buried three days later in the cemetery of the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Québec City. His burial record described him as a shopkeeper. His son, Louis Jr., attended the burial.

1820 burial of Louis Demuth (Ancestry)

The Quebec Gazette | La gazette de Québec, March 23, 1820 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Quebec Gazette | La gazette de Québec, March 30, 1820 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

As was customary at the time, an after-death inventory was created to document all the goods owned by Louis and Pélagie. The 47-page document, meticulously drafted by notary Charles Dugal, listed every single object the couple owned, from kitchen utensils to bedding, clothing, and tools. Louis’s store inventory was also detailed, alongside his debts and real estate holdings, providing a comprehensive snapshot of their possessions and financial status.

Excerpt of the 1820 inventory, showing the items found in the attic (FamilySearch)

A description of Louis Demutt’s real estate holdings in The Quebec Gazette | La gazette de Québec, June 8, 1820 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

“Demuth, Ludwig (* ca. 1756),” Hessische Truppen in Amerika (https://www.lagis-hessen.de/en/subjects/idrec/sn/hetrina/id/11567 : accessed 14 Nov 2024), Hessisches Institut für Landesgeschichte.

Robert Oakley Slagle, “THE VON LOSSBERG REGIMENT: A CHRONICLE OF HESSIAN PARTICIPATION IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION,” thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The American University, 1965, digitized by ProQuest (https://doi.org/10.57912/23870496.v1: accessed 18 Nov 2024).

Dale Pappas, “Who Were the Hessians in the American Revolution?,” The Collector (https://www.thecollector.com/who-were-hessians-american-revolution/ : accessed 18 Nov 2024).

“Read the Revolution: Hessians,” Museum of the American Revolution (https://www.amrevmuseum.org/read-the-revolution/hessians : accessed 18 Nov 2024), citing Friederike Baer in Hessians: German Soldiers in the American Revolutionary War, 11 May 2022.

“Trenton,” American Battlefield Trust (https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/trenton : accessed 19 Nov 2024).

Andrew A. Zellers-Frederick, “The Hessians Who Escaped Washington’s Trap at Trenton,” Journal of the American Revolution (https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/04/the-hessians-who-escaped-washingtons-trap-at-trenton/ : accessed 19 Nov 2024), 18 Apr 2018.

“Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures)," digitized images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/5404867 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), marriage of Henry Baacke and Marianne Pouillot, 30 Jan 1787, Québec (Anglican, Metropolitan Church); citing original data : Gabriel Drouin, Drouin Collection, Institut Généalogique Drouin, Montréal, Quebec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/234276 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), baptism of Marie Luce Blanchet, 12 Sep 1760, St-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud (St-Pierre-du-Sud).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/5404995 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), marriage of Lewis Damut and Mary Blanchette, 2 Jun 1794, Québec (Anglican, Metropolitan Church).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/2413044 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), burial of Marie Blanche, 19 Oct 1807, Québec (Notre-Dame-de-Québec).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/Membership/LAFRANCE/acte/5405657 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), marriage of Louis Dumate and Pelagie Dauphin, 25 Nov 1815, Québec (Presbyterian, Saint Andrew's Church).

“Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968,” digitized images, Ancestry.ca (https://www.ancestry.ca/imageviewer/collections/1091/images/d13p_1609b1097?pId=12825988 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), burial of Louis Demutt, 24 Feb 1820, Anglican Cathedral Holy Trinity Church.

"Actes de notaire, 1781-1794 : Pierre-Louis Descheneaux," digitized images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-53LZ-33Z5?cat=746680&i=2687 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), property sale from Joseph Blouin to Louis Demutt, 9 Oct 1792, images 2688-2692 of 2940; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Actes de notaire, 1816-1855 : Charles Dugal," digitized images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-R3LC-7TC7?cat=746877&i=2458 : accessed 26 Nov 2024), inventory of Louis Demutt and Pélagie Dauphin, 23 Mar 1820, images 2459-2505 of 2800; citing original data: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

“Land Petitions of Lower Canada,” digitized images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/land/land-petitions-lower-canada-1764-1841/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=24129& : accessed 25 Nov 2024), 1799 land petition by Lewis Demuth (vol. 199, page 94203-94221, microfilm reel C-2567, reference RG 1 L3L, item 24129), 1802 land petition by Louis Demuth (vol. 9, page 2647, microfilm reel C-2495, reference RG 1 L3L, item 24130) and 1802 land petition by Louis Demuth (vol. 9, page 2649, microfilm reel C-2495, reference RG 1 L3L, item 24131).

"Inventaire des documents de la Cour des sessions générales de la paix et de la Cour des sessions de la paix, district judiciaire de Québec, surtout 1800-1927 - Noms de famille débutant par D à H," online database, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://www2.banq.qc.ca/archives/genealogie_histoire_familiale/ressources/bd/recherche.html?id=THEMIS_2_DH&2 : accessed 26 Nov 2024), Certificate of good conduct for Louis Demutt), 5 Mar 1804 ; citing original data : Archives nationales à Québec, TL31,S1,SS1 (Contenant 1960-01-357/74), no 1123.

“Recensement paroissial de Notre-Dame-de-Québec, 1815," online database, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://www2.banq.qc.ca/archives/genealogie_histoire_familiale/ressources/bd/recherche.html?id=RECENSEMENT_1815 : accessed 25 Nov 2024), entry for Louis Démout (Demuth, Demutt), 60, house 10379, household 10554 ; citing original data : Archives de la paroisse de Notre-Dame-de-Québec, MS43. Visite du faubourg Saint-Jean commencée le 17 juillet 1815 et finie le 17 août 1815, p. 189.

“Recensement paroissial de Notre-Dame-de-Québec, 1818," online database, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://www2.banq.qc.ca/archives/genealogie_histoire_familiale/ressources/bd/recherche.html?id=RECEN1818_20170823 : accessed 26 Nov 2024), entry for Louis Demout (Demuth), 60, house 11193, household 11870; citing original data : Archives de la paroisse de Notre-Dame-de-Québec, CM1/F1, 7, p. 141.

Kim Kujawski, “Ancient French-Canadian Burial Places,” The French-Canadian Genealogist (https://www.tfcg.ca/ancient-french-canadian-burial-places : accessed 21 Aug 2023).