Ancient French-Canadian Burial Places

Most of our ancestors were buried in the parish cemetery when they died. But that wasn’t always the case. Let’s examine the final resting places that appear in the burial records of our French-Canadian ancestors, from New France to Quebec, including the cemetery for the poor, the Hôtel-Dieu or Hôpital-général cemeteries, inside the church, temporary resting places, and more.

Cliquez ici pour la version française

Ancient French-Canadian Burial Places

Most of our French-Canadian ancestors were buried in the “cimetière de la paroisse,” or the parish cemetery. But that wasn’t always the case. Let’s examine the final resting places that appear in the burial records of our French-Canadian ancestors, from the days of New France to Canada.

The Parish Cemetery | Le cimetière de la paroisse

The overwhelming majority of our French-Canadian ancestors were indeed buried in the local parish cemetery. It was a space reserved for the interment of the deceased, adjoining, close to, or even under, the church. The prevailing belief was that the closer one was buried to the church, the more they would benefit from the prayers said within and gain faster access to the gates of heaven. This idea was also the reason for burials within the church walls.

The burial of Marie Godin on October 27, 1687, in the parish cemetery of Saints-Anges in Lachine (FamilySearch)

Typically located in the centre of a town or village, the cemetery was an important part of religious and social life. It was enclosed by a masonry wall or a fence of stakes, separating the living and the departed. In the days of New France, tombstones and markers did not exist, with the exception of some simple crosses. Graves could be individual or communal, and they were almost all anonymous. There were no family plots as we know them today, and the tradition of burying spouses next to each other would only come much later.

Old church in Tadoussac (circa 1898 photo by William Notman & Son,McCord Museum)

Innu church and cemetery in Pointe-Bleue (Mashteuiatsh) (circa 1892 photo by William Notman & Son, McCord Museum)

As its name implies, the parish cemetery was reserved for the parishioners of a specific church, and Catholic rules prohibited the burials of certain individuals: those of different religions, heretics, children that weren’t baptized, those with questionable morals, along with those who died of suicide. Exceptions did happen, especially with the deaths of young children or if an additional donation was made to the church. Indigenous people were also buried in the parish cemetery if they had converted to Catholicism.

Jean Baptiste KiȢet, an Algonquin chief, was buried in the parish cemetery of Trois-Rivières on October 27, 1747 (FamilySearch)

A mass was normally celebrated for the deceased, attended by family and friends. Contrary to modern tradition, the family did not participate or attend the burial of the dead. This was a simple affair attended by a small number of people (that’s why we often see the names of unknown or unrelated witnesses in the burial record of our ancestors, as these were often people who worked for the cemetery or church).

In New France, the cost of a funeral service and burial would cost 25 livres. This included the mass, a cemetery interment, the services of the beadle or churchwarden, the coffin (likely a communal coffin used by the parish), the church cantors, and the altar boys.

Cross of the first cemetery of Québec seen from Montmorency Park (2012 photo by Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons)

Did you know?

The oldest Catholic cemetery in Canada is the Cimetière de la côte de la Montagne in Québec. It was established by Samuel de Champlain in 1608 as the final resting place of some 300 French colonists and indigenous Catholics. It was officially closed in 1691, the year the Sainte-Anne cemetery was founded. Visitors to Québec City today will find a large cross and two plaques to commemorate the old burial ground.

The oldest cemeteries in Québec were the Cimetière de la côte de la Montagne, the Cimetière de la Sainte-Famille (1657), the Cimetière Saint-Joseph (1657), the Cimetière des Pauvres de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Québec (1662), the Cimetière Sainte-Anne (1691), and the Cimetière des Picotés (1701).

Inside The Chapel, Church or Cathedral | À l’intérieur de la chapelle, église ou cathédrale

Intramural church burials are an ancient Christian tradition that early colonists brought from France. They were called “ad sanctos,” meaning close to the saints. French tradition dictated that the privilege was mainly reserved for clergy and nobles. In New France, however, burials within church walls were not restricted to this group of elites. They were performed for those belonging to the most powerful social groups (which could even include farmers), those who were most successful in their trade and those who were committed to their church and community. Bodies were placed in the crypt (or cellar) located under the floor of the church, or in a grave dug after raising the floor or a church bench.

The 1698 burial record of Louis de Buade, comte de Frontenac, Governor General of New France, in the church of the Récollets priests in Québec City (FamilySearch)

The funeral rites that accompanied an ad sanctos burial were generally more elaborate and expensive than those performed for a cemetery burial. Most people simply could not afford it or preferred to humbly lie with the poor or within the parish cemetery. The practice of intramural church burials disappeared from most parishes by the mid-nineteenth century, mainly due to public hygiene concerns and a lack of space.

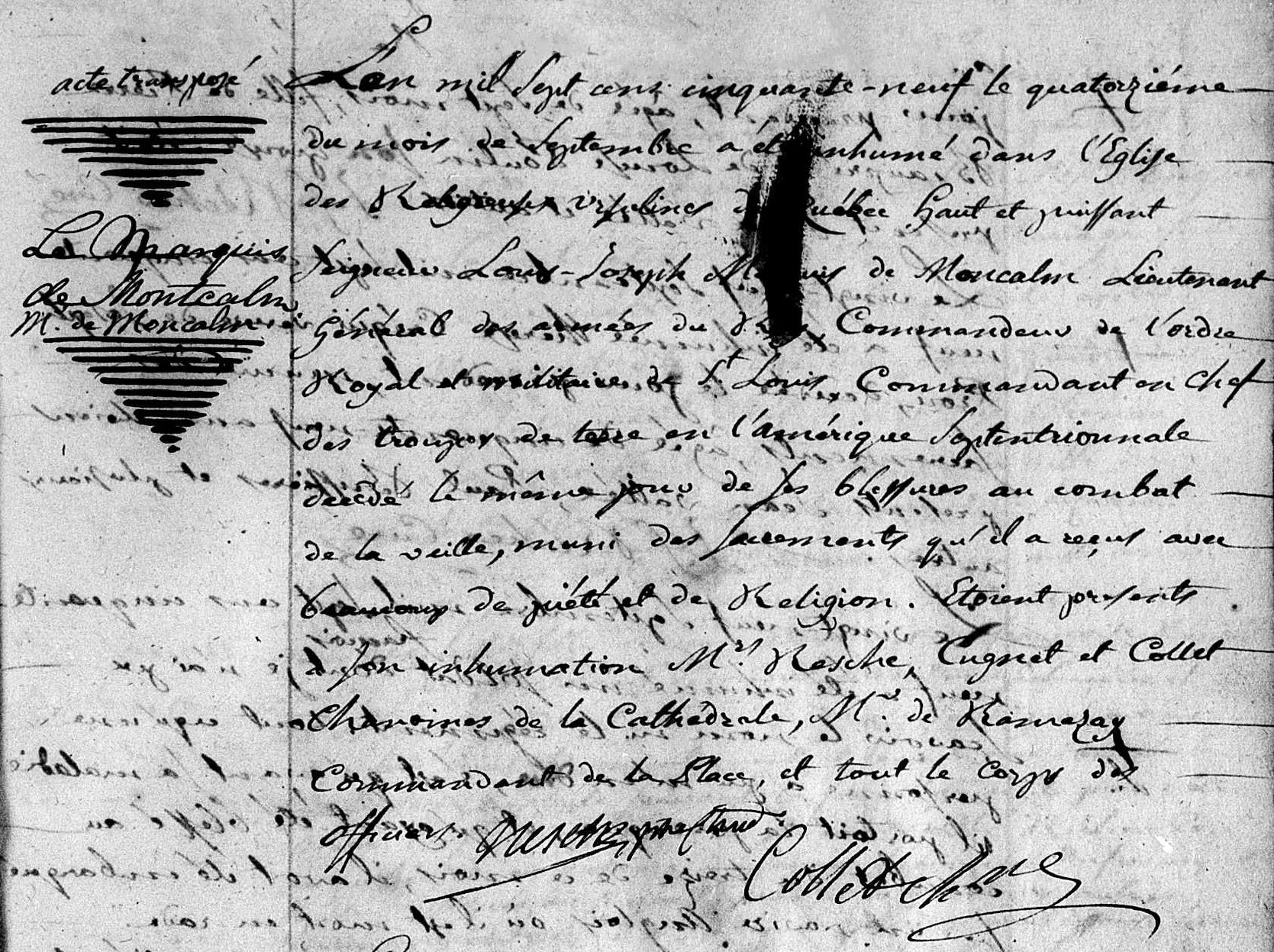

The September 14, 1759, burial record of Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Lieutenant General in the French forces in New France, interred in the church of the Ursuline nuns of Québec (FamilySearch)

Montcalm’s skull on exhibit at the Ursulines de Québec, circa 1930 photo (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

At least 900 people were buried within the walls of Notre-Dame Basilica-Cathedral in Québec City. Laypeople were interred there until 1877, after which time only the burial of clergy was allowed in the crypt.

Burial records can specify exactly where a person was interred in the church. Here are a few examples:

dans les voutes (in the vault)

dans le sanctuaire de l’église (in the church sanctuary),

près des balustres, sous le cœur (near the balusters, under the choir)

sous la cloche (under the bell)

sous le marche-pied de l’autel (under the altar step)

au-dessous de la première marche du grand autel (below the first step of the high altar)

sous le sanctuaire (under the sanctuary)

dans la crypte (in the crypt)

dans le caveau (in the vault)

sous le banc familial (under the family bench)

sous le banc seigneurial (under the seigniorial bench)

le long du mur (along the wall)

à environ cinq pieds de la balustrade (about five feet from the railing)

The Cemetery for the Poor | Le cimetière des pauvres

Québec, Montréal and Trois-Rivières all had a Cimetière des pauvres dedicated to the interment of the poor. Québec’s cemetery opened in 1661 and was expanded in 1663 and again in 1679. Located next to the Hôtel-Dieu, it was used by the nuns of the Augustines de la Miséricorde de Jésus to bury those who died there until 1857. It was the final resting place for many soldiers who died during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763).

Curiously, it wasn’t only the poor who were interred in Québec’s Cimetière des pauvres. Noble men and women, and those who were part of society’s upper classes chose to be buried there as a form of end-of-life repentance and humility.

The 1665 burial of Augustin de Saffray de Mezy, the first governor of New France, who expressed his desire to be buried in Québec’s cemetery for the poor in his last will and testament (FamilySearch)

In Trois-Rivières, the Cimetière des pauvres was opened in 1700 and had its last burial in 1834. Located in front of their convent, the cemetery was used by the Ursuline nuns for those who died at the Ursuline hospital (officially called Hôtel-Dieu de Trois-Rivières). In 1870, the remains were exhumed and transferred to the Cimetière Saint-Louis.

Ursulines Convent in Trois Rivières, about 1865 (McCord Museum)

In Montréal, the Cimetière des pauvres was nicknamed “La Poudrière,” as it was close to a powder magazine. Opened in 1749, it was located at the corner of present-day Saint-Jacques Ouest and Saint-Jean streets. It was enlarged several times to make room for more burials. In 1799, it was decided that the cemetery was too close to the city’s houses and posed a health risk, marking the end of burials at La Poudrière. A new plot of land was purchased for burials, called Cimetière Saint-Antoine. It was located in present-day Dorchester Square (should you visit the Square, notice the memorial crosses embedded in the park’s walkways). About 55,000 people were estimated to be buried there.

The cemeteries for the poor were also the final resting place for many of the colony’s enslaved persons, either black or indigenous.

The burial record for an unnamed 7-year-old female “panis” (an enslaved indigenous person), belonging to Henry Jeannot dit Bourguignon, buried in the cimetière des pauvres in Montréal on February 28, 1767 (FamilySearch)

The Cemetery of the Hôtel-Dieu | Le cimetière de l’Hôtel-Dieu

"Québec A.D. 1800. L'Hôtel Dieu" (drawing created between 1850 and 1923, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

"Hôtel-Dieu" translates as "God Hotel," or "Hostel of God." This institution was not an establishment providing accommodation, but rather a hospital. Its name stems from the fact that the Hôtel-Dieu was staffed by nuns. They were there to care for the souls, and not necessarily the bodies, of their patients. In the time of New France, Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal all had a Hôtel-Dieu.

Along with the cemetery for the poor, the Hôtel-Dieu in Québec also had several other cemeteries located around the hospital. The burial records for the deceased simply stated that they were “inhumé dans le cimetière de l’Hôtel-Dieu” (buried in the Hôtel-Dieu cemetery) or “dans le cimetière de l’hôpital” (in the hospital cemetery). Nuns were buried in the “cimetière des religieuses” (cemetery for the nuns).

In these entries from Québec City’s Hôtel-Dieu register, we see the 1758 burials of a French soldier, Joseph Morel dit Bourguignon, and an English prisoner of war, Thomas [Magrye?] (FamilySearch)

Legally speaking, Catholicism was the only religion recognized in New France. When a “heretic” was sick or injured, they were still cared for at the Hôtel-Dieu or the general hospital. If they died, however, they would not be buried at the hospital cemetery. The deceased would be buried somewhere off the property. The entry below for a French Huguenot soldier reads:

“Jean Simon dit Sansregret, soldier of the Company of Noyelle, native of Poitou, entered this Hôtel-Dieu on June 13, 1734, and he died on the 31st aged 34, without ever wanting to receive the sacraments, though the priests and the nuns worked with great zeal to win him over; he was buried by our orderlies near the barracks without honour and without prayers, and with the horror he inspired.” [our translation]

The burial of Jean Simon dit Sansregret on 31 June, 1734 (FamilySearch)

In Montréal, the Hôtel-Dieu cemetery was used for burials from 1654 to 1672. It was located at the present-day corner of St-Paul Ouest and St-Sulpice.

The Cemetery of the Hôpital-Général | Le cimetière de l’Hôpital-Général

Similar to the Hôtel-Dieu, New France’s general hospitals also had their own cemeteries.

In Québec, land and buildings were acquired from the Récollets in 1692 in order to establish the colony’s first general hospital, located near the Saint-Charles River. A year after the acquisition, the hospital’s management was handed over to the Augustines de la Miséricorde de Jésus, who also ran the Hôtel-Dieu. The nuns took in the poor, sick, disabled and elderly. The hospital had its own chapel, Notre-Dame-des-Anges, which meant that the hospital cemetery was also a parish cemetery. The first burial was recorded in 1728.

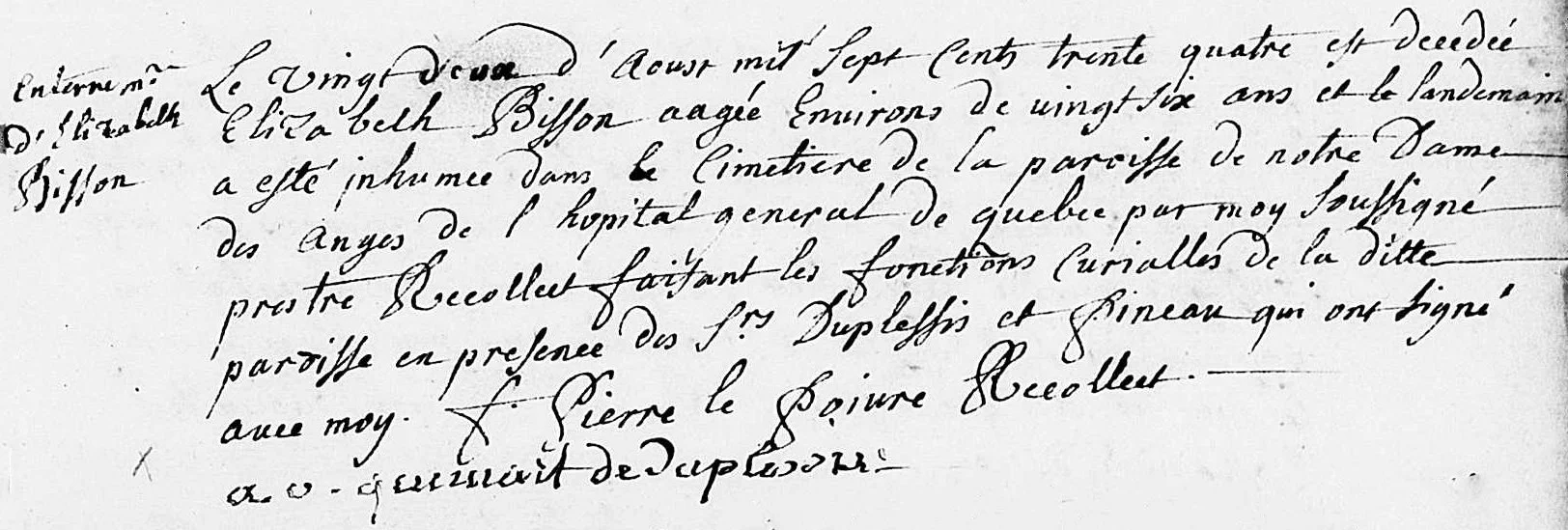

The 1734 burial of Elizabeth Bisson in the “cemetery of the parish of Notre Dame des Anges of the General Hospital” (FamilySearch)

The mausoleum of Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, in the cemetery of the Hôpital-Général de Québec (photo by Jstremblay, Wikimedia Commons)

During the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), the general hospital served as a military hospital for both allied and enemy soldiers. Its cemetery is the final resting place for about 4,000 soldiers who died during the conflict, with non-Catholics buried outside of the consecrated area. The remains of Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, commander of the French Armed Forces in New France, were moved to a mausoleum in the heart of the General Hospital’s cemetery in 2001. The section dedicated to the fallen soldiers has been called the cemetery of heroes.

The 1760 burial entries for two captains and a lieutenant during the Siege of Québec at Québec’s General Hospital (FamilySearch)

Eighteenth-century drawing of the Charon Brothers General Hospital attributed to Étienne Mongolfier (Wikimedia Commons)

In Montréal, the first general hospital was called Hôpital général des frères Charon. Located outside of the city walls at Pointe-à-Callières, it opened its doors in 1694. As a charitable foundation, its main objective was to care of the poor. The first burial recorded in the general hospital register was in 1725. In 1747, management of the hospital was transferred to the Sainte-Marie-Marguerite d’Youville and the Ordre des Sœurs Grises (the Grey Nuns). In addition to its main cemetery, the hospital also had its own cemetery for the poor.

1717 map of Ville-Marie (Montréal) showing the Charon Brothers’ General Hospital and the Hôtel-Dieu (Archives de Montréal)

The Charnel House | Le Charnier

The charnel house of the Sainte-Pétronille cemetery, Île-d’Orléans (©2022 The French-Canadian Genealogist)

Generally speaking, the charnier, or charnel house, refers to a location where several bodies or bones are kept, including catacombs and mass graves. In New France, the charnier, the chapelle des morts (chapel of the dead) and the caveau d’hiver (winter vault) were places where bodies were temporarily kept during the winter months when graves could not be dug. Once the ground thawed, the gravedigger could bury the dead. Before the use of these structures, a large pauper’s grave would be dug in the fall. The deceased would be placed there, and the grave covered with wooden planks.

The 1752 burial of Joseph Bricau in Québec City; the “char” in the margin most likely refers to “charnier” (FamilySearch)

The chapel of the dead was slightly larger than the charnel house and could be more elaborate in style. It is likely, however, that both terminologies were used interchangeably. The chapel was normally located at the edge of the cemetery. Services could be performed here instead of in the church, and in some cases, the chapel could be used as a vault and vice versa.

The charnel house of the Saint-Cyrille Church in Saint-Cyrille-de-Wendover (2018 photo Challwa, Wikimedia Commons)

The charnel house of the Sainte-Famille cemetery on Île-d’Orléans (Christian Lemire 2006, © Ministère de la Culture et des Communications)

The charnel house in Sainte-Hénédine (2019 photo by Cantons-de-l'Est, Wikimedia Commons)

Cemeteries for Epidemic Victims | Cimetières pour les victimes d'épidémies

Our ancestors saw their fair share of epidemics and pandemics: the flu, cholera, smallpox and typhus, to name a few. When mortality rates spiked, local cemeteries simply ran out of space. If there was room, some cemeteries created separate sections for the mass burial of victims. When there was no space at all, officials rushed to find new burial grounds.

In Québec City, an outbreak of influenza in 1700 and 1701 saw the creation of a new cemetery near the Hôtel-Dieu, at the corner of Hamel and Couillard Streets. In 1702 and 1703, a smallpox epidemic devastated the city. Many of its victims were buried in this cemetery, earning it the nickname “cimetière des picotés” (which translates loosely as cemetery for the poxed). Due to hygiene concerns (and noxious odours), the cemetery was closed in 1857.

In 1832, well-founded fears spread throughout Québec that immigrants arriving by ship would bring cholera to Canadian shores. In an effort to prevent the disease from reaching Québec, a quarantine station was opened at Grosse-Île. It soon became apparent that ships were indeed carrying the dreaded disease, and cholera ran rampant on the overcrowded quarantine island. Many infected people were asymptomatic, and no one knew how cholera was transmitted from person to person. Some ships carrying infected passengers were simply allowed to continue on to Québec, leading to an outbreak. On Grosse-Île, a cemetery was established southwest of Baie du choléra. The cemetery was also used during the 1847 typhus epidemic. Most of those victims were Irish, and the cemetery was dubbed “Cimetière des Irlandais.”

Cemetery at Grosse-Île (circa 1900 photo by Studio Livernois, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

As cholera ravaged Québec for the first time in 1832, a new cemetery quickly opened, officially called Cimetière Saint-Louis and Cimetière Saint-Patrick, and unofficially the “cimetière des cholériques” (cemetery of the choleric). It was located at the middle of the present-day quadrant formed by Grande-Allée Est, de Maisonneuve, de Salaberry and Louis-Saint-Laurent streets. The northern part of the cemetery was reserved for French-Canadians, the southern part for the Irish, hence its two names.

The entry below shows the first mass burial of 54 cholera victims at the Saint-Louis cemetery. All the dead were from the Emigrants' Hospital in Québec. Their names, ages and professions were unknown.

1832 mass burial in the Cimetière Saint-Louis (FamilySearch)

1860 map showing the boundaries of the old Roman Catholic Cemetery, drawn by H. M. Perrault (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Cover of the Canadian Illustrated News on 27 May 1871: “Unearthing the dead to make way for the living” (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Protestant Cemetery | Le cimetière protestant

Saint-Matthews Cemetery in Québec City was the first Anglican and Presbyterian cemetery established in Québec, and it still exists today. Located between Saint-Jean and Saint-Joachim Streets, and Saint-Augustin Street and Côte Saint-Geneviève, it no longer serves as a burial ground, but rather as an urban park. The old Saint-Matthews Church now houses a library.

The so-called “Protestant Burial Ground” was opened in 1771 after an influx of British settlers arrived in the city following the Battle of Québec in 1759. The cemetery was enlarged in 1778 and closed permanently in 1860 due to a lack of space. Between 6,000 and 10,000 people are estimated to be buried here, the majority in unmarked graves. There are over 300 tombstones still standing, one of which is probably the oldest tombstone in the province. If you visit the old cemetery, a podcast is available to guide you.

“The enveloped tombstone” (2012 photo by Malimage, Wikimedia Commons)

The old Saint-Matthews church and cemetery (2020 photo by Jean Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons)

In Montréal, the oldest Protestant cemetery was called Dorchester Cemetery. It was also known as Dufferin Square Cemetery and Saint-Laurent Cemetery. Located at the corner of Dorchester Street (present-day René-Lévesque Boulevard West) and Chenneville Street (Saint-Urbain Street), the cemetery was opened around 1797. The last burial took place in 1854. Today, it’s the site of the Complexe Guy-Favreau government building.

The Jewish Cemetery | Le cimetière juif

North America’s very first Jewish cemetery was founded in Montréal in 1776, located at the corner of Saint-Janvier (present-day de la Gauchetière Street) and Saint-François-de-Sales (Peel Street). Today, it’s the site of Saint-George’s Anglican Church.

The very first burial was that of Lazarus David, a British-born merchant and landowner. The David family would donate a plot of land in 1777 for the construction of the Shearith Israel Synagogue.

The Indigenous Cemetery | Le cimetière autochtone

Contrary to Christian cemeteries, indigenous cemeteries and burial practices vary widely based on the culture and history of the particular nation or community, as well as the period and geographic location. Cemeteries can be located in a populated or an isolated area. In most indigenous cultures, the living have an obligation to bury their relatives appropriately and in a suitable location, and to protect them from any disturbance or desecration.

Indigenous burying ground near Yale, British Columbia (1887 photo by William McFarlane Notman, McCord Museum)

The Cemetery of the Fort | Le cimetière du fort

Fort Chambly, circa 1840 (print by William Henry Bartlett, Wikimedia Commons)

Military conflicts between France and England or the Haudenosaunee (then called the Iroquois) meant that soldiers were often stationed in forts, fighting in battles far from their homes in towns and villages. If they died on the battlefield, their bodies may not have been returned to their parishes. Several burial records indicate that a soldier was “inhumé dans le cimetière du fort” (or “de ce fort”).

For example, on August 19, 1756, at Fort Saint-Frédéric, “the body of Jean Tanguay, militiaman of the parish of Saint-Valier, was buried with the usual ceremonies, in the cemetery of this Fort, aged eighteen years or so.”

Temporary Burial Places

Sometimes a record will indicate a temporary burial location, usually because of war and the need to bury bodies quickly. Here are a few examples.

After the Lachine Massacre of 1689, many victims’ bodies were hastily buried in and around the village. In 1694, the parish priest and several villagers exhumed their remains and reburied them in the Saints-Anges parish cemetery.

An extract of the October 28, 1694, entry in the Lachine register: “from there we went to the dwelling of the deceased Noël Charnois dit Duplessis, where having searched at the place where there was a wooden cross planted, we found the bones of the said Charnois and a little further we searched and found the bones of the deceased André Danis dit Larpenty, who had been killed and burned by the Iroquois on the said day and year above [August 5, 1689]” (FamilySearch)

A July 2, 1690, burial record in the register of Pointe-aux-Trembles indicates that a group of men, including the lieutenant Coulombe, the surgeon Jean Jalot dit Desgroseilliers and the surgeon Antoine Chaudillon were killed by the Iroquois at the top (“le haut”) of the island of Montréal. All the victims were hastily buried there. Over four years later, on November 2, 1694, their bones were transported and buried in the cemetery of Pointe-aux-Trembles.

On November 21, 1759, the parish registers of Saint-Michel indicate that six bodies were buried in the cemetery, after being temporarily “interred in the concessions during the Siege of Québec” since July.

The 1759 reburial of six persons in the parish cemetery of Saint-Michel (FamilySearch)

Unknown Burial Places

Finally, there are burial locations that were never recorded in New France. Some of our ancestors simply dropped off the public record and were presumed dead, their bodies never having been discovered. Causes of death could include drowning, shipwrecks, enemy attacks, or accidents far from home.

Burial locations were also unknown for those found guilty of crimes and condemned to death. Perhaps the most famous example is the execution of Marie-Josephte Corriveau (nicknamed “La Corriveau”), a so-called witch found guilty of murdering her husband. After her body was publicly “hanged in chains” (a type of cage) for five weeks, Governor Murray allowed it to be removed and buried “où bon vous semblera” (where you see fit).

Many bodies were simply “jeté à la voirie” (public places, normally muddy and near roads, where rubbish was dumped). It is likely that a cemetery also existed near the executioner’s residence and that the bodies of those condemned to death were interred there.

1912 drawing of La Corriveau by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte (Wikimedia Commons)

The May 25, 1763, ordinance of Governor Murray, permitting the removal of La Corriveau’s body (Université de Montréal)

Buy this article in PDF format

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Article written by Kim Kujawski on 21 July 2022.

Sources:

Marc Beaudoin, "Histoires de cimetières," conference presented at the Société historique du Cap-Rouge, 18 Nov 2004, published in the Bulletin de la Société Historique du Cap-Rouge (SHCR), number 18 spring 2005 (https://www.shcr.qc.ca/file/si1476226/download/numero18-2005-fi24885040.pdf).

Charles Bourget, "Les chapelles funéraires et les cimetières. Une évolution notable entre le 17e et le 20e siècles", 2007, Fondation du patrimoine religieux du Québec (http://mail.patrimoine-religieux.qc.ca/fr/pdf/documents/Chapelles_funeraires.pdf).

Le Devoir, "Le cimetière des Picotés," 28 Jul 2008 (https://www.ledevoir.com/non-classe/199420/le-cimetiere-des-picotes).

Gouvernement du Québec, "Ancien hôpital général de Montréal," Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec (https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/rpcq/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=96641&type=bien).

Government of Canada, Lieu historique national du Canada de l'Hôpital-des-Sœurs-Grises, Lieux patrimoniaux du Canada (https://www.historicplaces.ca/fr/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=9651).

Lorraine Guay, "L’évolution de l’espace de la mort à Québec," 1991, Continuité, (49), 24–27, digitized by Érudit (https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/continuite/1991-n49-continuite1052191/17792ac.pdf).

Lise Jolin, "Les cimetières de Montréal," 30 Jul 2008, Planète Généalogie et Histoire (http://www.genealogieplanete.com/blog/view/id_2965/title_Les-cimeti-res-de-Montr-al/)

Daniel Labelle, Répertoire des cimetières du Québec (http://www.leslabelle.com/cimetieres/CimMain.asp).

André Lachance, Vivre, aimer et mourir en Nouvelle-France; Juger et punir en Nouvelle-France: la vie quotidienne aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Montréal, Québec: Éditions Libre Expression, 2004), 189-193.

Siméon Mondou, Les premiers cimetières catholiques de Montréal et l’indicateur du cimetière actuel (Montréal, E. Sénécal & Fils, 1887), digitized by Wikisource (https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Les_premiers_cimeti%C3%A8res_catholiques_de_Montr%C3%A9al_et_l%E2%80%99indicateur_du_cimeti%C3%A8re_actuel).

NelsonWeb, “Des cimetières à Québec sous le Régime français 1608-1759," Je me souviens (https://jemesouviens.biz/cimetieres-quebec-regime-francais/); citing original data : Paul-Victor Charland, "Notre-Dame de Québec. Le Nécrologe de la Crypte ou Les inhumations dans cette église depuis 1652", dans Bulletin des recherches historiques, vol. XXI, no. 5, (mai 1914), pp. 136-151; ibid., vol. XXII, no. 6, pp. 169-181; ibid., vol. II, no. 7, pp. 205-217;.; ibid., vol. II, no. 8, pp. 237-251; ibid., vol. II, no. 9, pp. 269-280; ibid., vol. II, no. 10, pp. 301-313; ; ibid., vol. II, no. 11, pp. 333-347 ; ANDQ, op. cit., vol. 89-200; Paul-Victor Charland, loc. cit., vol. II, no. 11, pp. 341-342; Pierre-Georges Roy, op. cit., pp. 30-68.

Vanessa Oliver-Lloyd, Le patrimoine archéologique des cimetières euroquébécois ; étude produite dans le cadre de la participation du Québec au Répertoire canadien des lieux patrimoniaux, volet archéologique (Québec : Ministère de la culture, des communications et de la condition féminine, 2010), digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2008323).

Louise Pothier, "Vivre ses morts," 1998, Continuité, (76), 9–10, digitized by Érudit (https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/continuite/1998-n76-continuite1055437/17060ac.pdf).

Québec Cité, "St. Matthew's Church and graveyard,” (https://www.quebec-cite.com/en/businesses/st-matthews-church-and-graveyard).

Société historique de Québec, "Voici 10 anciens cimetières situés dans le Vieux-Québec," 2 Jun 2019, Le Journal de Québec (https://www.journaldequebec.com/2019/06/02/voici-10-anciens-cimetieres-situes-dans-le-vieux-quebec).

Cyprien Tanguay, À travers les registres (Montréal: Librairie Saint-Joseph, Cadieux & Derome, 1886).

Jean-René Thuot, "La pratique de l’inhumation dans l’église dans Lanaudière entre 1810 et 1860 : entre privilège, reconnaissance et concours de circonstances", 2006, Études d'histoire religieuse, 72, 75–96, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/1006589ar).

Marcel Trudel, L'Esclavage au Canada français : histoire et conditions de l'esclavage (Québec : les Presses universitaires Laval, 1960), digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/3187835).

Ville de Montréal, "Le cimetière catholique Saint-Antoine," 19 Jan 2016, Mémoires des Montréalais (https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/memoiresdesmontrealais/le-cimetiere-catholique-saint-antoine).

Record Sources:

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," digitized images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L993-43PR?i=360&cc=1321742&cat=299358), burial of Marie Godin, 27 Oct 1687, Lachine > Saints-Anges-de-Lachine > Index 1676-1710, 1711, 1717-1859 Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1676-1778 > image 361 of 862; citing original data: Archives nationales du Québec, Montréal.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G99Q-H9SL-Z?i=666&cc=1321742&cat=242611), burial of Jean Baptiste KiȢet, 27 Oct 1747, Trois-Rivières > Immaculée Conception > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1634-1749 > image 667 of 684.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8993-F931-L?i=176&cc=1321742&cat=242176), burial of Louis de Buade, comte de Frontenac, 1 Dec 1698, Québec > Notre-Dame-de-Québec > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1691-1712 > image 177 of 556.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G99Q-9KLV?i=57), sépulture de Louis Joseph de Montcalm, 14 Sep 1759, Québec > Notre-Dame-de-Québec > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1759-1768 > image 58 of 599.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G993-WDMW?i=14), burial of Simon Berguin dit Labonté, 28 Feb 1757, Les Cèdres > Saint-Joseph-de-Soulanges > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1752-1762 > image 15 of 36.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8993-F9SQ-C?i=229&cc=1321742&cat=242176), burial of Messire Augustin de Saffray Seigneur de Mezy, 5 May 1665, Québec > Notre-Dame-de-Québec > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1621-1679 > image 230 of 512.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9MY-TP1Q?i=29&cc=1321742&cat=46693), burial of an unnamed 7-year-old female “panis” belonging to Henry Jeannot dit Bourguignon, 28 Feb 1767, Montréal > Notre-Dame > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1767-1781 > image 30 of 1593.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G993-DCWG?i=173&cc=1321742&cat=341812), burial of Joseph Morel dit Bourguignon, 10 Dec 1758, and Thomas [Magrye?], 26 Dec 1758, Québec > Hôtel-Dieu de Québec > Sépultures 1723-1857 > image 174 of 632.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G993-DC9G?i=50&cc=1321742&cat=341812), burial of Jean Simon dit Sansregret, died 31 Jul 1734, Québec > Hôtel-Dieu de Québec > Sépultures 1723-1857 > image 51 of 632.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L99Q-M9QY-J?i=98&cc=1321742&cat=66843), burial of Elizabeth Bisson, 23 Aug 1734, Québec > Notre-Dame-des-Anges > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1728-1876 > image 99 of 528.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G99Q-M931-K?i=209&cc=1321742&cat=66843), burials of the captains Martin and de Montreuil and lieutenant de Pahaunai, 9 and 10 May 1760, Québec > Notre-Dame-des-Anges > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1728-1876 > image 210 of 528.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G99Q-MJ9M?i=14&cc=1321742), burial of Joseph Bricau, 2 Dec 1752, Québec > Notre-Dame-de-Québec > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1752-1757 > image 15 of 416.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-899Q-MFDM?i=95&wc=HCX6-PTL%3A17585101%2C19508101%2C29803301&cc=1321742), mass burial of 54 anonymous persons, Québec > Notre-Dame-de-Québec > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1832 > image 96 of 382.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8993-432P?i=380&cc=1321742&cat=299358), reburial of several persons, 28 Oct 1694, Lachine > Saints-Anges-de-Lachine > Index 1676-1710, 1711, 1717-1859 Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1676-1778 > images 381-382 of 862.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8993-F5FK?i=335&cc=1321742&cat=58318), burial of six persons, 21 Nov 1759, Saint-Michel-de-Bellechasse > Saint-Michel > Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1693-1789 > image 1467 of 1712.

Ordonnances, ordres, reglemens [sic] et proclamations durant le gouvernement militaire en [sic] Canada, du 28e oct. 1760 au 28e juillet 1764, Textes réglementaires du Gouverneur Murray (https://calypso.bib.umontreal.ca/digital/collection/_murray/id/1441/rec/1), p. 116. Université de Montréal.