A Brief History of Montreal's Griffintown

Explore the history of Montreal's Griffintown neighbourhood, once dubbed "the city below the hill." Long associated with Irish immigrants, Griffintown played a significant role in the industrialization of the city. It also suffered immensely: poverty, fires, heavy pollution and flooding were ever-present. Not to mention religious strife, murder and lead-contaminated beer…

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

A Brief History of Griffintown

The Irish "City Below the Hill"

The Griff

The history of Montreal's Griffintown neighbourhood begins shortly after the founding of Montreal itself. On May 17, 1642, Montreal—or Ville-Marie as it was then called—was established by Paul de Chomedey and Jeanne Mance as a missionary colony. Mance founded the Hôtel-Dieu in Montreal and was largely responsible for securing donations from France to keep the colony running.

In 1654, Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve, granted Mance and the Hôtel-Dieu a 112-arpent plot of land called "the fief of Nazareth." Mance and the sisters from the Hôtel-Dieu looked after the fief. It was also called "la grange des pauvres", or the "barn for the poor", as any proceeds derived from the land were used to benefit the Hôtel-Dieu and its charitable works. Those revenues mostly came from farming. At the turn of the century, a small chapel called Sainte-Anne was constructed at the edge of the property. The surrounding area became known as "quartier Sainte-Anne", and later "St. Anne's Ward", which encompassed Griffintown and the eastern part of Pointe-Saint-Charles.

“1805, map of the fief of Nazareth,” Archives de la Ville de Montréal.

"Portrait of Thomas McCord," 1816 oil painting by Louis Dulongpré, McCord Museum.

Irish merchant Thomas McCord leased the fief of Nazareth from the Sœurs hospitalières de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal in 1791, intending to continue farming the land. While he was away on a trip to Ireland, McCord asked his associate Patrick Langan to handle his Montreal affairs in his absence. The unscrupulous Lagan illegally sold the lease to Mary Griffin, the wife of soap manufacturer Robert Griffin. Located on the shores of the future Lachine canal and adjacent to Ville-Marie, the fief was in a strategic position with great potential. Griffin made an agreement with the Sisters to further subdivide the land and build low-cost housing, the proceeds from which would be shared with the nuns. In search of affordable homes, many working-class Irish immigrants moved into the neighbourhood. New streets were planned: King, Queen, Prince, Nazareth, Gabriel (now Ottawa) and Griffin (now Wellington). Griffin called the new neighbourhood "Griffintown." Its initial boundaries were Mountain, William, des Sœurs-Grises and De la Commune streets.

Upon returning to Montreal in 1805, Thomas McCord sued Mary Griffin and Patrick Langan for the illegal purchase of his lease. He eventually won his case in 1814 and tried to remove the Griffin name from Montreal maps. He was too late: the name "Griffintown" was already well-entrenched. Despite her legal troubles, Mary Griffin is still considered by many to be the de facto founder of Griffintown. The future Parc Mary-Griffin was named in her honour and will be located at the corner of Ann and Ottawa Streets.

An Irish Influx

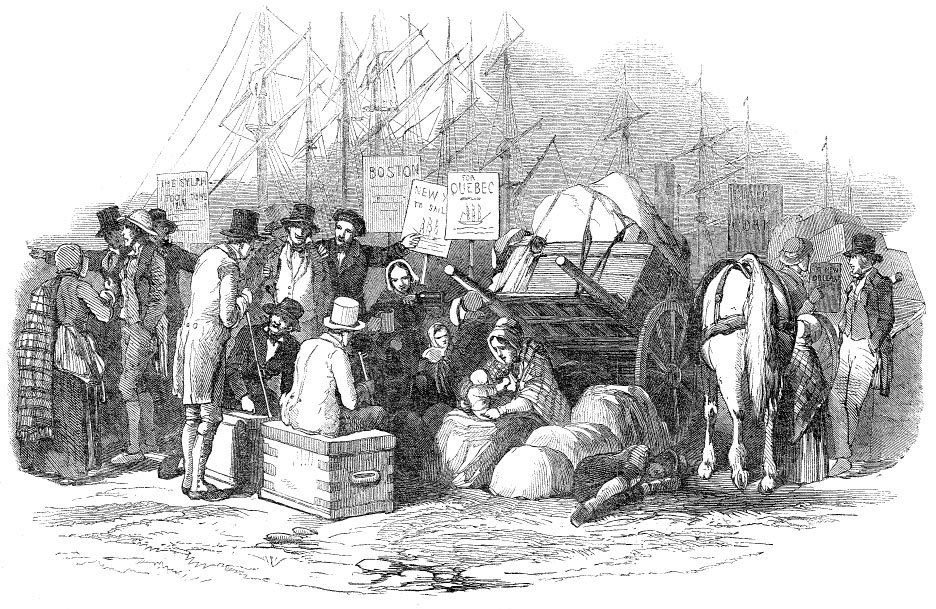

In the early 19th century, Griffintown slowly transitioned from a mainly agricultural community to a residential one. Starting from about 1815, most Irish immigrants landing in Montreal chose to settle in the southern part of Griffintown, where lodging was inexpensive. The digging of the long-planned Lachine Canal from 1821 to 1825 attracted about 1,000 workers, most of them Irishmen. Irish emigration to Canada was encouraged by British authorities, who saw an opportunity for cheap and plentiful labour. For the Irish, it was an opportunity to leave a difficult life behind, especially during the Great Famine of the 1840s. Though people from other communities did live in Griffintown (French Canadians, English and Scottish), it became strongly associated with the Irish. The very first St. Patrick's Day parade in Canada took place on March 17th, 1824, passing through Griffintown and St. Henri.

The Lachine Canal

When the Lachine Canal opened in 1825 to bypass the Lachine Rapids, it had a depth of only 1.5 metres. This soon proved inadequate, and a new project to deepen the canal was undertaken in 1843. Again, most of the labourers were Irish. A typical workday was brutal: 15 hours of digging with few breaks. Most men made roughly 3 shillings per day (about 60 cents). Workers lived in overcrowded and dirty shanties and were obliged to buy their provisions from company stores. When salaries were reduced to 2 shillings per day in early 1843, it triggered the first significant strike in Canadian history. The workers wanted better pay, delivered on time, and the right to smoke whenever they wanted.

To shine a light on their cause, the strikers staged both violent and peaceful protests in Montreal and along the Lachine Canal. To complicate matters, not all workers were on the same page. The francophones didn't agree with the anglophones. The Irish were divided between Catholic and Protestant. Physical fights erupted on a regular basis between the strikers and those still working. These tensions culminated in June of 1843 along the section of canal in Beauharnois, when police fired on the strikers, killing eight men.

"The Lachine Canal Laborers' Strike," 1878 print by Henri Julien, McCord Museum.

Article in The Quebec Gazette, 28 Jun 1843.

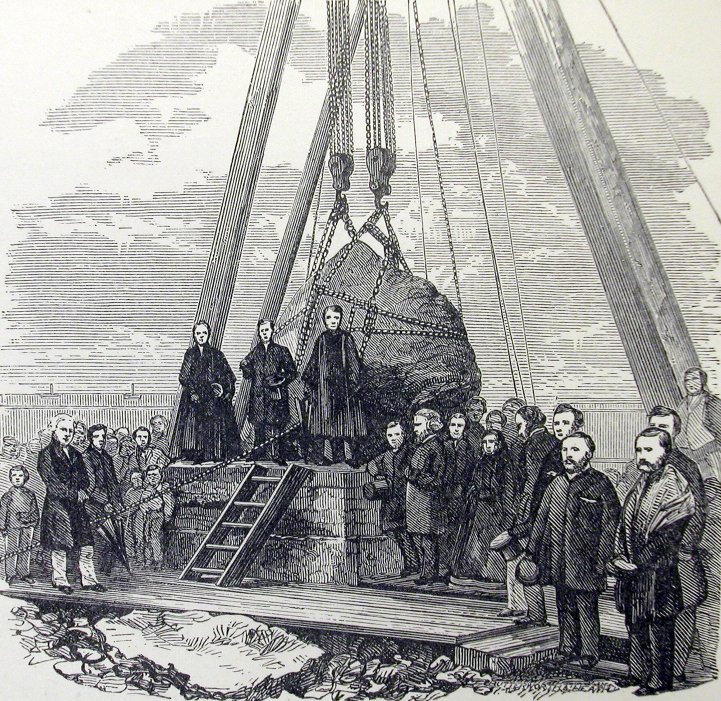

“Laying the Monumental stone, marking the graves of 6000 immigrants near Victoria Bridge,” 1860 wood engraving, McCord Museum.

Fleeing the famine, more and more Irish immigrants arrived around 1847. The boats sailing from the British Isles also brought a typhus epidemic to Canadian shores. About 6,000 Irish immigrants died of the disease in so-called "fever sheds". Of those who survived, many took jobs working on the canal expansion.

By 1849, the second stage of the canal expansion was finally completed. Another important development around this time was the installation of railroad tracks along the canal, as well as the construction of the Victoria Bridge, completed in 1859. During the construction of the bridge, a mass grave of typhus victims was discovered. The workers, most of them Irish, erected the "black rock" monument in their honour.

The final phase of construction on the Lachine Canal occurred between 1874 to 1885. After this expansion, the average canal width was 45 metres, and the average depth was 4.3 metres. The rail system was also improved, stretching the entire length of the canal. This allowed merchandise to be easily transported in and out of warehouses.

Lachine Canal Construction

An Industrial Revolution

"Interior of workshop," engraving by John Henry Walker, 19th century, McCord Museum

From the late 1840s to the early 1870s, the area surrounding the Lachine Canal became the industrial hub of Canada. Plenty of labourers from Griffintown were available for hire at low wages. The economy was shifting from one primarily driven by artisans to one fuelled by larger companies using the latest in mechanics and technology. Montreal companies based in Griffintown manufactured flour, shoes, metal products, engines, beer, clothing, chocolate and sugar for the rest of the country. An ever-increasing portion of these goods was also exported to the United States.

Several businesses were operating in the area before the industrial boom. William Smith founded a brickyard in 1816 and the Eagle Foundry Company also set up shop a few years later. The construction of the canal, however, was the impetus for an influx of new industry. One newcomer was Dow Brewery, one of the first breweries in Griffintown. Its owner, William Dow, purchased a large warehouse on William Street in 1844. About 15 years later, Dow bought a nearby plot of land between William and Notre-Dame streets, on which he built a brewery. (Dow later became infamous when it introduced lead into its fermentation process, making their customers very ill. Facing a public relations nightmare, the company donated some of their land to the city and funded the construction of the Montreal Planetarium.) Several businesses specializing in keg- and barrel-making opened nearby.

Griffintown Industry

One of the largest businesses in Griffintown was Bartley and Dunbar's St. Lawrence Engine Works, employing over 160 men. It manufactured engines, boilers, castings and other metal products. Another large company was the Redpath sugar refinery, able to produce 6,000 barrels of sugar per month. The employees working in these large manufacturers weren't all men. F. W. Harris' cotton factory employed 70 people, almost all of them women and children. Warehouses, factories and mills lined the canal. By the 1860s, over 50 businesses were operating in Griffintown. Despite the booming industry around them, most residents of Griffintown lived in poverty. They were also exposed to industry smoke, waste and smells.

"Montreal from Street Railway Power House chimney, QC, 1896", photo by William Notman & Son, McCord Museum.

Excerpt from the 1861 Canadian census for St. Ann’s Ward, showing a household of Irish-born men and women with a variety of occupations: cooper, tailor, printer and clerk.

"Église de Sainte-Anne de Montréal," circa 1930 photo, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

An Irish Church for Griffintown

As more and more Irish settled into Griffintown in the middle of the 19th century, the need was growing for a place of worship. St. Ann's Catholic Church was founded in 1854, becoming a parish in 1880. It also advocated for the poor and helped the community by offering social services. St. Ann's is the second oldest church in Montreal catering to the Irish community. The first, St. Patrick's, was founded in 1847.

A Hard Life

Simply put, life in Griffintown was hard. Housing was shoddy and cramped, allowing diseases like typhus, smallpox and cholera to spread easily. Most families did not have running water. The canal brought sewage and contaminated water near or even in, people's homes. Discharge from tanneries, slaughterhouses and factories all ended up in the canal. In 1897, only one in four Griffintown dwellings was equipped with indoor flush toilets. By the turn of the century, 30,000 people lived in Griffintown. As immigration continued, the housing situation only deteriorated. These slum-like conditions affected the health of the community and contributed to Montreal having the worst infant mortality rate in the country.

Living by the canal brought about additional challenges. After the winter thaw and the ice break-up on the St. Lawrence, there was always the chance of flooding. And Griffintown did experience many catastrophic floods—in 1861, 1865, 1869, 1884 and 1885. The worst flood occurred on April 17, 1886, causing significant damage to homes, halting all railway traffic and shutting down factories. Most of Griffintown was underwater in the span of a few hours. By the evening, Notre-Dame Street was under 6 feet of water. Read more about the historic flood here. The seasonal flooding only came to an end in 1899, when a flood-wall was erected.

Because Griffintown's wood-frame houses were built so close together, the risk of fire was also present. In 1845, all the buildings between Queen Street and Nazareth Street were gutted by fire. In 1852, a fire from a carpenter's shop destroyed almost half the houses and buildings in Griffintown, leaving 500 families homeless.

Charles "Joe Beef" McKiernan, Wikimedia Commons.

Joe Beef

Within sight of Montreal's Golden Square Mile, it was clear that Griffintown's working class lived in far different conditions, earning it the nickname the "city below the hill". One person who worked to alleviate the social issues that plagued Griffintown was Charles "Joe Beef" McKiernan. He ran a tavern that offered food, drink and lodging, in addition to social services. [Yes, the famous Montreal restaurant is named in Joe Beef's honour, although the restaurant is not located where the tavern once stood on de la Commune Street.] A community leader and talented orator, he defended workers' rights during the Lachine Canal disputes. He also lobbied for better services for Griffintown residents.

“Joe Beef’s Canteen,” from Joe Beef of Montreal, the Son of the People, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library, 1879.

The Original Joe Beef’s Canteen on the corner of de la Commune and Callières, Google (2021).

Religious Strife

If diseases, floods, fires and poor living conditions weren't enough, Griffintown was also plagued by religious in-fighting. There were clear divisions between the Protestants from Northern Ireland and the Catholics from Ireland. Sectarian tensions tended to flare up on St. Patrick's Day (March 17) and Glorious Twelfth (an Ulster Protestant celebration on July 12). In 1853, clashes erupted between Protestants and Catholics during the Haymarket Square riot, following a speech by Alessandro Gavazzi, a provocative anti-Catholic preacher. Ten people, all Irish Catholics, died from gunshot wounds.

Haunted Griffintown

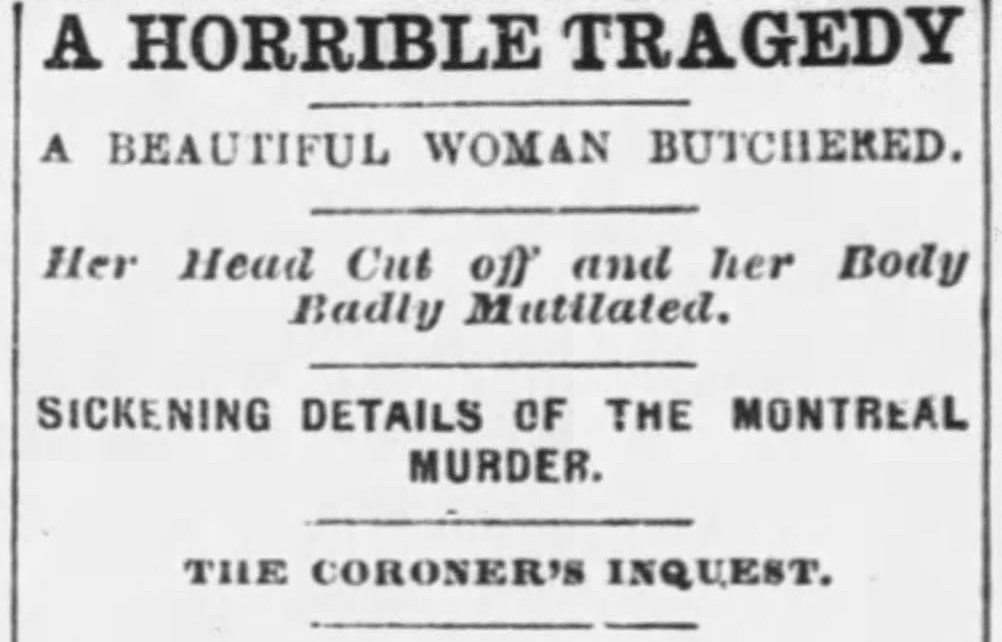

Several ghosts call Griffintown home. The most famous of them all is Mary Gallagher. A prostitute, she was beheaded with an axe in 1879 by her jealous rival Susan Kennedy during an alcohol-fuelled altercation. Her ghost is said to return to the corner of William and Murray every 7 years on June 27th (known to locals as "Mary Gallagher Day") as she searches for her head.

Headline in The Ottawa Daily Citizen, June 30, 1879

Headline in The Gazette, June 28, 1879

The Wellington Tunnel, closed in 1994, is also said to be haunted. The spirit of a man nicknamed "Bucket of Blood" has been seen inside the tunnel. Before his death, the man worked at a slaughterhouse in Griffintown and walked home to Point St. Charles every night through the tunnel. He always carried a bucket of blood home so his wife could make blood pudding. Nearby, the ghost of young Arthur Carr is said to haunt the Swing Bridge, after being killed there in an accident in 1908.

In 1944, a Royal Air Force bomber plane crashed into tenement housing at the intersection of Ottawa and Shannon Streets in Griffintown, killing 15 people. Some of the victims are said to haunt the crash site. And though it no longer exists, the location of St. Ann's Church is also said to be haunted. Witnesses have reported seeing ghostly apparitions of funeral processions.

There are plenty more ghost stories from in and around Griffintown. Check out Haunted Montreal's blog to read more.

The Griffintown "Shamrock Club lacrosse team, Champions of the World, composite, 1879," McCord Museum.

"Montreal from Street Railway Power House chimney, QC, 1896", photo by William Notman & Son, McCord Museum.

Letter to the Editor in The Montreal Daily Star, November 17, 1936

Irish Exodus

The Irish population started leaving Griffintown in the 20th century. As their prosperity grew post-WWII, they moved to other parts of Montreal, Canada or even the United States. Jewish and Italian immigrants moved to Griffintown in the 1920s. By 1960, the majority of residents were of Italian or Ukrainian descent. In 1970, St. Anne's Church was demolished because of a lack of parishioners, marking the end of an era.

In 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened, forever changing the neighbourhoods around the Lachine Canal. The Seaway was much deeper and wider than the canal, allowing for larger vessels to travel from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through a series of locks. Traffic on the canal slowed down dramatically. In 1963, Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau rezoned the entirety of Griffintown to become a light industrial area. He also announced the construction of the Bonaventure Expressway (completed in 1967), effectively splitting Griffintown in two. Many buildings, including workers' row houses, were destroyed to make way for new industrial buildings and the new highway. The upcoming Expo 67 was the incentive for clearing the so-called "slums" of Griffintown. The canal closed permanently in 1970. A year later, the population of Griffintown had dwindled to a measly 800 residents. Residents either chose to move away or were forced to do so. Griffintown became a derelict ghost town.

Griffintown in the News

Present-day Griffintown is bordered by Notre-Dame Street on the north, McGill Street on the east, des Seigneurs street to the west and the Lachine Canal to the south. In recent years, efforts have been made to revitalize the neighbourhood. Businesses moved into the industrial buildings and warehouses were converted to apartment buildings. Today, Griffintown is primarily residential, a gentrified neighbourhood with a trendy restaurant and entertainment scene. The canal is again in use, mostly by small pleasure crafts and kayaks, and a paved 12-kilometre bike path runs its entire length from Lachine to Old Montreal.

The Lachine Canal bike path passes remnants of an industrial past (© The French-Canadian Genealogist 2022).

The south side of the Canal, with the old Canada Sugar Refinery in the background (© The French-Canadian Genealogist 2022).

Take a Tour of Griffintown (in person or virtually!)

Lisa Gasior has created a listening guide called "Sounding Griffintown." Download a self-guided tour map, and its associated sounds, here. The Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network has created a “Heritage Trail of Griffintown and Point St. Charles.” You can download their pamphlet and map here.

Can't make it to Montreal? Check out this excellent virtual tour by G. Scott MacLeod, "The Death and Life of Griffintown: 21 stories."

Enjoying our articles and resources? Consider showing your support by making a donation. Every contribution, no matter how small, helps us pay for website hosting and allows us to create more content relating to French-Canadian genealogy and history.

Thank you! Merci!

Sources & Further Reading:

John Matthew Barlow, " 'The House of the Irish': Irishness, History, and Memory in Griffintown, Montreal, 1868-2009," Thesis in the Department of History, 2009, Concordia University (https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/002/NR63386.PDF).

Dave Flavell, Community and the human spirit : oral histories from Montreal's Point St. Charles, Griffintown and Goose Village (Ottawa : Petra Books, 2015), digitized by Library and Archives Canada (https://bac-lac.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1035291308?lang=en&new=-8585567297694852375).

Dan Horner, "Solemn Processions and Terrifying Violence: Spectacle, Authority, and Citizenship during the Lachine Canal Strike of 1843,", 2010, Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 38(2), 36–47, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/039673ar).

John Kalbfleisch, "Labourers' struggle ended in bloodshed," 14 Jun 2017, The Montreal Gazette (https://montrealgazette.com/sponsored/mtl-375th/from-the-archives-labourers-struggle-ended-in-bloodshed).

Robert D. Lewis, "The development of an early suburban industrial district: The Montreal ward of Saint-Ann, 1851–71," 1991, Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 19(3), 166–180, digitized by Érudit (https://doi.org/10.7202/1017591ar).

G. Scott MacLeod, "Dans l’Griff-In Griffintown: Three personal French Canadian narratives on their homes, public spaces, and buildings in the former industrial neighbourhood of Griffintown," Thesis in the Department of Art Education, 2013, Concordia University (https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/977057/1/MACLEOD_MA_S2013.pdf).

Diane Sabourin, "Griffintown," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada (https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/griffintown), published 6 Mar 2012, last edited 16 Apr 2015.