Michel André dit St-Michel & Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau

Journey back to 17th-century New France, where the André family endured the horrors of the Lachine Massacre of 1689. Their story is one of resilience and survival in a world shaped by conflict and loss.

Cliquez ici pour la version en français

Surviving the Storm: The André Family and the Lachine Massacre

Location of La Cambe in France (Mapcarta)

Michel André dit St-Michel, the son of Richard André and Jeanne Poirier, was born around 1639 in the parish of Notre-Dame in La Cambe, Normandy, France.

Today, La Cambe is a small rural commune in the Calvados department, with a population of about 500 residents. It is best known for its German cemetery from the Second World War, which is the final resting place of 21,222 soldiers who died in 1944. Nearby, a three-hectare peace garden features around 1,200 maple trees donated by supporters from around the world.

Church of Notre-Dame in La Cambe, late 19th century (photo by Paul Robert, Wikimedia Commons)

Upper village in La Cambe, 1909 (postcard, Geneanet)

New Beginnings in Montréal

Michel’s exact arrival date in New France is unknown. However, since his marriage contract was drawn up in May 1663 and boats did not travel during the winter, it is likely that Michel arrived in the fall of 1662.

In 1663, he was listed in the 11th squad of the milice de la Sainte-Famille (Holy Family Militia) in Montréal. This militia was established by Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, the founder and governor of Montréal, in response to the threat from indigenous groups, most notably the Iroquois (the Haudenosaunee), who had killed or captured several colonists since 1642. Maisonneuve organized the militia under the patronage of the Holy Family—Jesus, Mary, and Joseph—and called on the men of Montréal to form squads of seven, each electing a corporal. A total of 139 men volunteered, including Michel André dit Saint-Michel.

“On the advice given to us from various places that the Iroquois had formed a plan to take this habitation by surprise or by force, and as His Majesty’s help has not yet arrived, whereas this island belongs to the Blessed Virgin, we thought it our duty to invite and urge those who are zealous in her service to join together in squads of seven people each, and after having elected a corporal by a plurality of votes, to come find us to be enrolled in our garrison and, in this capacity, to follow our orders for the preservation and proper management of this habitation, promising on our part to ensure that, besides the dangers that may be encountered on military occasions, private interests will not be harmed. In addition, we promise all those who enlist for the aforementioned purposes to remove them from the roll whenever and wherever they request us to do so. We order Sieur Dupuis, Major, to have the present order inscribed at the registry of this place together with the names of those who will be enrolled as a result of this order, to serve as a mark of honour, as having laid down their lives for the interests of Our Lady and public salvation.”

"French Canadian Militia," 1910 watercolour by Mary Elizabeth Bonham (Wikimedia Commons)

As a militiaman, Michel would have patrolled the St. Lawrence River, stood guard at the settlement walls at night, and escorted farmers to their fields during the day. The assistance that Maisonneuve had requested finally arrived in 1665 with the arrival of the Carignan-Salières regiment. Subsequently, the milice de la Sainte-Famille was disbanded in 1666.

The church of Saint-Jean in Courcelles-la-Forêt (photo by Labiloute, Wikimedia Commons)

Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau, the daughter of Jacques Nadreau and Marie Lebrun (or Brun), was born on November 3, 1642. She was baptized “Françoise Jacquine” on October 20, 1644, in the parish of Saint-Jean in Courcelles, Maine, France (modern-day Courcelles-la-Forêt, in the Sarthe department of the Loire region). Her father was a master architect and stonecutter. Her godparents were Jacques Dubou[set?] and Françoise de Voynes.

Located about 200 kilometres southwest of Paris, Courcelles-la-Forêt is a small village with a population of around 400 residents, known as Courcellais. It lies about ten kilometres north of La Flèche, a town that was the place of origin for dozens of other emigrants to New France.

1644 baptism of Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau (Archives de la Sarthe)

Location of Courcelles-la-Forêt in France (Mapcarta)

Françoise Jacqueline lost her father at the age of three and her mother at seven. Little is known about her life between 1650 and 1658; she may have been taken in by relatives, sent to a charitable institution, or placed in religious care. It's also possible she worked as a servant during this time. Whatever her circumstances, at the age of 15, Françoise Jacqueline made the bold decision to leave France in search of new opportunities across the ocean. She became a "fille à marier," or marriageable girl, possibly recruited from the nearby town of La Flèche.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Aug 2024)

From Marriage to Mourning

The first mention of Françoise Jacqueline in New France is in 1658, at her wedding. At just 15 years old, she married her first husband, the miller Michel Louvard dit Desjardins, on September 23, 1658, in the parish church of Notre-Dame in Montréal. The couple did not have any children before Michel’s death on June 23, 1662. According to his burial record, he was “assassinated on his doorstep we don't know by whom if not by the savage wolves who were at the house in large numbers.” [Some historians, including Peter Gagné, argue that the term “wolves” in this record does not refer to animals but to the Wolf Indians, who were reportedly drunk at the time of Michel’s murder. Gagné notes that an ordinance was passed the very next day, prohibiting anyone from “selling intoxicating beverages to the Savages, given the assassination of the said Desjardins, committed the previous night by drunken Savages.”]

1658 marriage of Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau and Michel Louvard dit Desjardins (Généalogie Québec)

1662 burial of Michel Louvard dit Desjardins (Généalogie Québec)

A New Chapter for Françoise Jacqueline

On May 20, 1663, notary Bénigne Basset dit Deslauriers drew up a marriage contract between Michel André dit St-Michel and Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau. Michel was described as an "habitant" (farmer) of Ville-Marie (later known as Montréal), with his father recorded as a "marchand bouvier" (an ox merchant or cattle trader). Françoise Jacqueline, also a resident of Ville-Marie, was the widow of Michel Louvard dit Desjardins. The contract adhered to the norms of the Coutume de Paris. While Michel was able to sign the document with a rather large signature, Françoise Jacqueline could not.

Michel and Françoise Jacqueline were married on June 18, 1663, in the parish church of Notre-Dame in Montréal. At the time of their wedding, Michel was about 24 years old, and Françoise Jacqueline was 20.

Last page of Michel and Françoise Jacqueline’s 1663 marriage contract (FamilySearch)

Michel and Françoise Jacqueline’s 1663 marriage record (Généalogie Québec)

Montreal, circa 1665: Plan of Ville-Marie and the first streets planned for the establishment of the Upper Town (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Michel and Françoise Jacqueline first settled in Montréal, where they had at least ten children, nine of whom were girls:

Marie Gertrude (1664–1665): Her burial record indicates that she drowned.

Marie Gertrude (1666–1689): She married François Philippon dit Maisonneuve on January 16, 1686, in Lachine. They had two daughters: Louise Madeleine (1686–?) and Marie (1687–1689).

Catherine (1668–1673): She tragically died while trying to escape from a barrel, where she was confined as punishment.

Jeanne (1670–1687): She married the surgeon Jean Michel dit Gascon on February 11, 1687, in Lachine. They had one son, Jean (1687-1687). Jeanne died of fever.

Philippe (1672–?): He was hired as a voyageur on May 31, 1695.

Pétronille (1674–1689) : She married the merchant Charles Beloncque dit Fugère on August 1, 1689, in Lachine.

Marguerite (ca. 1676–1751): She married François Vinet dit Larente on March 1, 1701, in Montréal. They had two children: Marguerite (1701–1745) and François (1703–1760). Marguerite later married her second husband, Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois, on June 25, 1704, in Lachine. They had seven children: Suzanne (1705–1775), Louis (1707–1789), Jacques (1709–1775), Ambroise (1711–1798), Marie Dorothée (1714–1794), Toussaint (1717–1791), and Marie Anne Clémence (1720–1758).

Marie (1678–?): There are no further details recorded about her life.

Marie Angélique (1680–?): There are no further details recorded about her life.

Louise Madeleine (1684–1684): She died a "natural death" and was the first person to be buried in the parish cemetery instead of the chapel. On November 21, 1687, her remains were exhumed, with permission granted by the Grand Vicar of Montréal, and reburied in the church of Lachine at the foot of the confessional.

In 1666, Michel and Françoise Jacqueline were recorded in the New France census living in Montréal. Michel was listed as an “habitant,” or farmer.

1666 census for the household of Michel André dit St-Michel (Library and Archives Canada)

A year later, the couple was recorded in the census still living in Montréal, along with their 14-month-old daughter, Gertrude. They owned six arpents of land under cultivation but had no farm animals.

1667 census for the household of Michel André dit St-Michel (Library and Archives Canada)

Property in New France

In the 1670s, Michel and Françoise Jacqueline were involved in several transactions, most of which were related to land.

On May 18, 1671, Michel sold a land concession located on the island of Montréal, in an area known as "côte Saint-Sulpice" or Lachine, to Mathieu Gervais dit Le Parisien for 30 livres. Michel was listed as a "habitant" of the island of Montréal. (Today, côte Saint-Sulpice corresponds to the western part of Lasalle and the eastern part of Lachine.) The plot of land measured two arpents of frontage along the shores of Lac Saint-Louis, extending 30 arpents deep. Michel had received this concession on August 31 of the previous year. In addition to the sale price, the buyer agreed to assume all future cens and rentes due on the property.

On June 11, 1673, Michel and Françoise Jacqueline exchanged a 15-arpent plot of land on the island of Montréal, located in the neighbourhood of Saint-Joseph, with Jean Leroy and Marie Demers for a 60-arpent plot of land on the island of Montréal, in an area known as "côte Saint-Louis" above "cap Saint-Gilles." (Today, the neighbourhood of Saint-Joseph is situated west of McGill Street in Montréal, and côte Saint-Louis corresponds to the eastern part of Lasalle.)

On October 8, 1673, Michel purchased a brown-haired ox, aged between seven and eight years, from Jean Leduc for 100 livres in furs or one gun.

On December 27, 1677, Michel purchased a land concession on the island of Montréal, in an area called Lac Saint-Louis, from Pierre Mallet and Marie Anne Hardy for 200 livres. (Today, Lac Saint-Louis corresponds to Lachine.) Michel was recorded as a resident of pointe Saint-Louis on the island of Montréal. The land measured one hundred arpents and was located on the shores of Lac Saint-Louis.

On December 10, 1678, the Séminaire de St-Sulpice de Paris, the seigneur and owner of the island of Montréal, requested that several plots of land at the tip of the upper part of the island be surveyed and a report produced. Michel’s land was included in this request.

The Tragic Death of a Daughter

In 1673, heartbreak struck the André family, bringing a tragic focus onto Françoise Jacqueline. In his book Faits curieux de l’histoire de Montréal (Curious Facts About Montréal's History), author Édouard-Zotique Massicotte dedicated three pages to the tragic death of Catherine.

Artificial intelligence image created by the author with Dall-E (Aug 2024)

On July 19 of that year, Françoise attempted to discipline her five-year-old daughter, Catherine, for misbehaving. She took Catherine to the barn, placed her in a barrel, and covered it with a plank weighed down by a sack of flour to prevent her escape. Tragically, when Françoise later returned to check on her daughter, she discovered that Catherine had died, having tried to escape but becoming trapped with her neck caught between the plank and the edge of the barrel.

Overwhelmed with fear and guilt, Françoise turned to Sister Marguerite Bourgeoys instead of immediately informing the authorities. Sister Bourgeoys promptly alerted the courts, and two surgeons, Jean Martinet de Fonblanche and Antoine Forestier, were called to examine the child’s body. An inquiry was held on July 21, during which witnesses confirmed that Françoise was a loving mother who had routinely disciplined her daughter by confining her in the barrel.

Despite the tragic outcome, Françoise faced no further legal consequences, and the case was closed without any charges against her.

Life on the Frontier in Lachine

Around 1676, the André family made the fateful decision to leave the town of Montréal and move to the small but growing settlement of Lachine. They initially settled in an area of Lachine known as La Présentation. That same year, as Michel and Françoise Jacqueline arrived, the parish of Saints-Anges-Gardiens was founded, and a modest chapel was built to serve the needs of the villagers. A few years after their arrival, the André family relocated further east to Lachine proper.

Reduced replica of the first Saints-Anges-Gardiens chapel, built in 1676, on the site of Fort Rémy (Lachine). The old church was built of timber only and measured 30 feet long by 26 feet wide. Photo by the French-Canadian Genealogist (all rights reserved).

Located southwest of Montréal on the shores of Lac Saint-Louis, Lachine was a key departure point for the fur trade into the Pays-d’en-Haut, a vast region encompassing the Great Lakes basin. The village was home to French settlers, soldiers, and fur traders who regularly interacted with local Indigenous groups, including the Iroquois, engaging in trade. However, tensions were high as French settlers increasingly encroached on Indigenous lands, and the threat of conflict was ever-present.

Several forts were built on the island of Montréal, including one in Lachine. Constructed in 1671, it was initially called Fort Lachine but was renamed Fort Rémy in 1680, in honour of the local priest. The fort also served as the local mill.

"Fort Rémy in 1671" (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In 1681, Michel and Françoise Jacqueline were recorded in the New France census as living on the island of Montréal, in the fief de Verdun (Lachine), with their seven children and a 34-year-old domestic servant named Jean. Michel was listed as a "tanneur," or tanner. The family owned a gun, eleven horned animals, and 16 arpents of land under cultivation.

Between 1684 and 1689, Michel was recorded as a "sergent de milice," or militia sergeant, in Lachine. During the years 1686 to 1689, he was also listed as a "laboureur," or ploughman.

The Island of Montréal in 1686, with the red square highlighting locations significant to the André family (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Trials and Tribulations of Françoise Jacqueline and her daughter Gertrude

Author Robert-Lionel Séguin, in his book La Vie libertine en Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle, provides a wealth of detailed information on Françoise-Jacqueline Nadreau (known as “la Saint-Michel”) and her daughter Gertrude André (known as “la Maisonneuve”).

"Tavern sign, late 17th century" (Canadian Museum of History)

Once the André family had settled in Lachine, Françoise Jacqueline, with her husband’s permission, opened a cabaret with a man named Vincent Dugas. Before long, she found herself at the center of several scandals involving her family. Françoise Jacqueline and her husband, Michel, were accused of tolerating indecent behaviour at the cabaret, including prostitution. She was not only rumoured to be allowing her daughter Gertrude to engage in immoral activities but also accused of illegally selling alcoholic beverages in their establishment.

In March of 1689, Françoise Jacqueline became embroiled in a series of public and legal disputes, primarily with the Boutentrain and Chambly families, as well as other habitants of Lachine, who accused her and her daughter of misconduct. Rémy, the parish priest of Lachine, filed a complaint against Françoise Jacqueline with the bailiff of Montréal. The accusations against her included not only exploiting her inn for scandalous activities but also launching verbal attacks in defence of her family's honour. On several occasions, Françoise tried to fight back against those who slandered her by lodging formal complaints. However, these efforts were not enough to curb the growing rumours and accusations, and her inn eventually became synonymous with debauchery in the community. Despite these troubles, she continued to run her cabaret until severe sanctions were imposed.

Gertrude, Françoise Jacqueline's daughter, was at the center of a scandal that erupted in Lachine. She was accused of engaging in immoral behaviour in public and open prostitution. Reports indicated that Gertrude had been seen in the company of several men, including a sergeant of the local garrison named Fougère, with whom she was caught in compromising situations.

The accusations against Gertrude were intensified by the rivalry between her family and other habitants of Lachine, particularly the Boutentrain couple (Simon Davraux dit Boutentrain and Perrine Filiatrault). The Boutentrains openly accused Gertrude of indecent behaviour, claiming to have caught her in clandestine meetings. Although several witnesses supported these accusations, many feared reprisals from Gertrude's "lovers" and requested "to be placed under the protection and safeguard of justice." In response to these allegations, Gertrude "was apprehended and imprisoned in the jail intended for girls and women of ill repute" for the duration of the trial. Witnesses were interrogated about Gertrude's "excessive and scandalous life."

The trial also revealed that Gertrude's own parents, Françoise Jacqueline and Michel, were accused of deliberately “prostituting their daughter” and allowing their inn to be used as a venue for these dubious encounters. This scandal highlighted the libertine climate that existed in parts of New France at the time, where cabarets and public houses often played a central role in social life, particularly for the soldiers stationed at the Lachine garrison.

Although he seemed to be less directly involved in the public complaints, Michel was also implicated in accusations relating to his daughter's misconduct and the management of their inn, where scandalous activities, including prostitution and the illegal sale of alcohol, were reported to have taken place.

Ultimately, these legal proceedings were never concluded due to the outbreak of the Lachine Massacre.

Tensions on the Brink: The Road to the Lachine Massacre

As Françoise Jacqueline painfully knew, many 17th-century colonists had lost their lives at the hands of Indigenous assailants, including her first husband. Conflicts with Indigenous groups, particularly the Iroquois Confederacy, had been ongoing for years, with frequent attacks on settlements like Ville-Marie (Montréal) and Trois-Rivières. These hostilities were part of the broader conflict known as the Beaver Wars (or Iroquois Wars), driven by France’s desire to control the fur trade and expand its territory in North America.

The Iroquois, a powerful confederation of five nations (later six) known as the Haudenosaunee, had their own expansionist goals. They saw the French presence as a direct threat to their fur trade with the Dutch and later the English in New York, which was a critical economic lifeline for their people. The competition over control of the fur trade intensified the conflict, leading the Iroquois to target French allies, such as the Huron, Algonquin, and other Indigenous nations who were allied with the French.

Inter-tribal rivalries also played a significant role, as warfare often broke out between the Iroquois and their traditional enemies, the Huron and Algonquin. These hostilities were not solely driven by economic factors but also by the desire to dominate the region and secure hunting grounds. The result was a cycle of violence that would eventually lead to large-scale attacks like the Lachine Massacre.

French military expeditions against Iroquois villages, led by Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac, frequently provoked raids and reprisals against French settlements. Several attempts at peace negotiations between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy ended in failure. Meanwhile, the British in New York openly supported the Iroquois by supplying them with weapons and encouraging attacks on the French whenever possible. Frontenac was recalled to France in 1682, unable to neutralize the ongoing Iroquois threat. His successors were Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre, who served as governor for two years, and Jacques de Meulles, who served for less than five months.

Governor Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville replaced De Meulles in 1685, marking the beginning of a new and more aggressive strategy against the Iroquois. Denonville's initial focus was on securing French territorial claims by conquering the English trading posts on Hudson Bay. Once this objective was completed, he turned his attention to the Iroquois. In 1687, Denonville left Montréal with an army of over two thousand men, consisting of French soldiers, militiamen, and allied Indigenous warriors. His campaign targeted the Tsonnontouan (Seneca) people, one of the five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (the others being the Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk). Although the Seneca initially resisted Denonville's forces, they were ultimately overwhelmed by superior numbers. Denonville's forces attacked several Seneca villages, systematically destroying homes and food supplies to weaken their resistance.

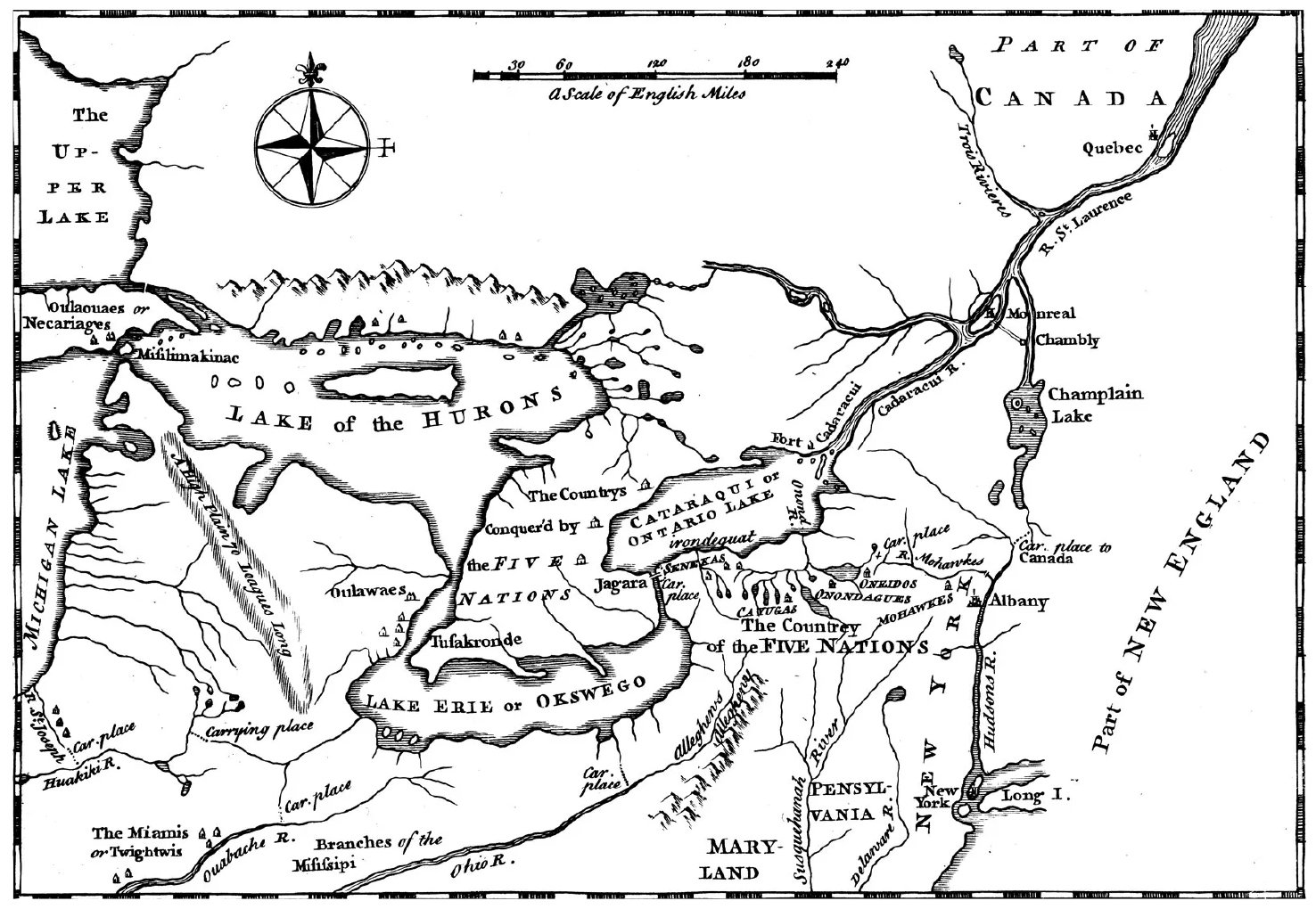

Map of the initial nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, from History of the Five Indian Nations Depending on the Province of New-York, by Cadwallader Colden, 1755 (Encyclopædia Britannica)

At Fort Frontenac (modern-day Kingston, Ontario) in the summer of 1687, Denonville extended an invitation to the Iroquois for a grand feast and peace talks. However, this gathering was a ploy aimed at capturing as many Iroquois leaders as possible. Over 220 captives were taken to Québec, with 36 of them sent to France to serve as galley slaves for the crown in Marseille. This deceitful act by Denonville was obviously seen as a profound betrayal by the Iroquois, eliminating any possibility of peace negotiations. In retaliation, the Iroquois escalated their raids on French villages and missionary settlements, intensifying the cycle of violence. This act of treachery by Denonville is widely regarded as a catalyst for the Lachine Massacre that followed.

In 1688, New France was devastated by a severe outbreak of smallpox and measles, which claimed the lives of over 10% of the colony's population. Faced with the decimation of his forces and unable to secure sufficient reinforcements to counter the Iroquois threat, Governor Denonville proposed peace talks. As a gesture of good faith, he returned four Iroquois hostages to their villages and invited their leaders to a meeting. At its conclusion, the parties agreed to hold further peace negotiations, which would include the five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. Denonville also promised to arrange the return of the Iroquois captives who had been sent to France. Although a fragile truce was established, tensions remained high.

In May 1689, before any additional peace talks could take place in Canada between the French and the Iroquois, England and France declared war on each other, marking the start of King William's War in North America. The New Englanders were the first to learn of the declaration and quickly informed their Iroquois allies. In New France, unaware that war had been declared, most colonists continued their daily lives in unfortified and vulnerable villages. Meanwhile, the Iroquois, now assured of full English support in their conflict, began planning their deadliest attack on the French colony.

“Fort Remy, 1689,” illustration by Albert Samuel Brodeur in 1893 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

The Attack on Lachine

At dawn on August 5, 1689, under cover of a violent hail and rainstorm, a force of between 1,200 to 1,500 Iroquois warriors—primarily Mohawk—descended on the village of Lachine, which then had about 320 residents. The attackers struck without warning, breaking down doors and windows, setting homes ablaze, and killing settlers. Although estimates vary widely, it is believed that around 24 settlers were killed in the massacre, while over 25 others were taken captive. Additionally, two settlers were injured, and more than 40 remained unaccounted for, likely killed or captured.

The raid lasted several hours and left the settlement in ruins. In total, 56 of the 77 houses in Lachine were burned to the ground, making it exceedingly difficult to recover or identify the bodies of victims. Notably, the nearby forts were left untouched during the attack.

"Lachine Massacre," painting by Jean-Baptiste Lagacé (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

In his History of Canada, François Vachon de Belmont, the superior of the Sulpicians of Montréal, described the aftermath of the Lachine Massacre:

“After this total victory, the unhappy band of prisoners was subjected to all the rage which the cruellest vengeance could inspire in these savages. They were taken to the far side of Lake St. Louis by the victorious army, which shouted ninety times while crossing to indicate the number of prisoners or scalps they had taken, saying, we have been tricked, Ononthio, we will trick you as well. Once they had landed, they lit fires, planted stakes in the ground, burned five Frenchmen, roasted six children, and grilled some others on the coals and ate them.”

Later, some prisoners managed to escape, while others were freed in prisoner exchanges. However, forty inhabitants of Lachine were never heard from again.

The André family was decimated by the massacre:

Michel, about 50 years old, and Françoise Jacqueline, aged 46, were never heard from again and presumed killed, although their bodies were never found.

Gertrude, aged 23, was also presumed murdered along with her 3-year-old daughter, Marie. Her 2-year-old daughter, Louise Madeleine, was likely taken prisoner. Gertrude’s husband, François Philippon dit Maisonneuve, had returned to France in 1688. Louise Madeleine reappears in the historical record on August 17, 1744, in Lachine, when she married André Rapin dit Skaianis at the age of 58, while he was 63. André was the adoptive son of André Rapin and Clémence Jarry. [According to genealogical literature, André was considered a Panis (an enslaved indigenous person in New France), but this claim is likely based solely on his nickname "Skaianis." The nickname does not appear until adulthood, and no documents explicitly state that he was a Panis.]

Philippe, then 17 years old, either escaped the massacre, was absent, or returned from captivity, as he reappears in the public record in 1695, hired as a voyageur in the fur trade. [There were no other men named Philippe André fitting the age range of 16 to 50 years old at that time in New France who could be identified as a voyageur.]

Pétronille, aged 15, was also presumed murdered alongside her husband, Charles Beloncque dit Fugère, whom she had married just four days before the massacre.

Marguerite, about 13 years old, was held captive until 1698.

Marie, aged 11, and Marie Angélique, aged 8, were never heard from again.

Meanwhile, Frontenac was on his way back to New France, as an exhausted Denonville had requested to be recalled. On November 15, 1689, Frontenac wrote to the minister of state, Jean-Baptiste Colbert:

“We were so frustrated by the bad weather that I was not able to arrive in Quebec until the evening of 12 October, and the ships carrying the King’s supplies and ammunition were not able to arrive until the 14th of the same month. I did not find either the Marquis de Denonville or Mr. de Champigny, who were both in Montreal, so all I could think about was joining them there.

The very next day, work began on unloading what was on the ships and I arranged for boats to load and carry to Montreal what was necessary. I also ordered that some boats be caulked to transport a detachment of habitants that I ordered for my escort and to serve in Montreal, if the opportunity arose. The bad weather and continuous rain meant that I was only able to leave at noon on the 20th of October and arrive in Montreal on the 27th.

It would be difficult to describe to you, Monseigneur, the general consternation I found among all the people and the despondency of the troops, the first of whom had not yet recovered from the fear they had had of seeing all the barns and houses burnt down at their gates, which were more than three leagues away in the canton called Lachine, taking more than 120 people with them, men, women and children, after having massacred more than 200 of whom they had broken the heads of some, burned, roasted and eaten the others, opened the bellies of pregnant women to tear out their children and committed cruelties that were unheard of and without example. ”

“Reception of Count de Frontenac during his return to Quebec in October 1689,” painting by Charles William Jefferys (Wikimedia Commons)

In October 1694, the parish priest and several villagers reburied the victims of the Lachine Massacre in the Saints-Anges parish cemetery. The parish register records the somber event as follows:

“Today, 28 October 1694, feast of Saint Simon and Saint Jude, by virtue of a certain order of Monsignor the Most Illustrious and Most Reverend Bishop of Québec dated 18 June last, signed Jean, bishop of Québec and countersigned by his secretary, found and sealed with the seal of his arms,

Following the publications and announcements that we made at the pulpit on two consecutive Sundays, we, Pierre Rémy, priest of the parish of Saints-Anges de Lachine on the Island of Montreal, at the end of the parish mass, went to the locations where the bodies of several inhabitants of this parish had been buried, both men and boys, women and girls, on August 5 of the year 1689, [where] the houses and barns of this parish were seized, ransacked and burned by the Iroquois, in order to exhume them and transport them to the cemetery of this parish, which could not have been done earlier either because of the incursions of the Iroquois, which have been frequent since that time, or because their flesh had not yet been consumed, and in order to transport and bury them in the cemetery of this parish, which we have done in the presence of several of our parishioners, those of whom who are able to sign have signed with us the present report as follows. […]

From there we went to the dwelling of André Rapein [Rapin] where, having dug into a hollow, we found five heads, including that of Perrine Fillastreau [Filiatrault], the wife of Simon Davaux dit Boutentrain, with her bones. Also, [we found] the head and bones of a lad we were told was a soldier, the heads of two children whose names we could not be told, which were with their bones, and the head of the late Marie [Geneviève] Cadieu [Cadieux], wife of André Canaple dit Valtagagne, whose bones we found in a pit at the foot of the great bastion of Fort Rolland. Next, we had part of the bones removed from the ground on the water’s edge, of two soldiers killed on August 6 of the aforementioned year in the Iroquois battle with the French, between Fort Remy, the church and Fort Rolland, as we were unable to exhume the rest of the bones due to the current overflow of water.”

The Iroquois raiders retreated with their prisoners, but the attack left a profound psychological impact on New France. It marked one of the bloodiest episodes in the long-standing Iroquois-French conflicts, which would not come to an end until the signing of the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701.

Today, the actual number of prisoners and victims of the Lachine Massacre remains a topic of debate. Some historians and anthropologists argue that contemporary accounts may have exaggerated the event, suggesting that the Iroquois were overly villainized to cast our French-Canadian ancestors as heroes. Conversely, others believe that modern interpretations, influenced by political correctness, have led to a reduction in the reported number of victims.

The Fate of Marguerite André dite St-Michel

Marguerite was about 13 years old at the time of the Lachine Massacre. She was taken prisoner during the attack and remained in captivity until 1698, when she was 22 years old.

On July 14, 1699, Marguerite reappeared in the public record by summoning notary Antoine Adhémar dit Saint-Martin to draft her last will and testament. According to the document, Marguerite was living “outside the city of Villemarie near the gate of Lachine,” in the home of “her good friend” Jean Quenet. Quenet was recorded as the controller of His Majesty’s farms in New France.

Though she was “currently lying in bed,” Marguerite was described as being “of sound mind and understanding.” As a “true Christian and Catholic,” she bequeathed her soul to God. She expressed her gratitude to Jean Quenet for “having purchased her from the hands of the Iroquois where she was a prisoner, and having fed her, and cared for her”[illegible sentence] “as if she were his own daughter.” In appreciation for his affection and friendship, Marguerite left him 2,000 livres to take [from her goods?] for the affection and good friendship he gave her. [The notary’s handwriting is extremely hard to read .]

Though Marguerite’s illness isn’t specified, it’s possible that she was a victim of the smallpox epidemic that struck the colony in 1699. Fortunately, she survived the ordeal.

Who was Jean Quenet?

Born in 1647 in Rouen, Jean Quenet came to New France around 1674 as a master hatter and hat merchant. He settled in Montréal and acquired land near the gate known as “de Lachine.” By 1677, he had become one of the main suppliers of hats in Montréal. As a hatter, Jean was deeply involved in buying furs from Indigenous hunters and trappers, which were essential for producing 17th-century hats. At times, he skirted the law to benefit his business; in 1680, he and several other men were fined 2,000 livres for contravening the King's order against coureurs de bois trading with “savages.”

Despite these setbacks, Jean became an influential figure in Montréal, eventually serving as the receiver of seigneurial duties for the island. He leveraged his connections with the Seminary to acquire valuable land holdings in Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne, and Lachine. How Jean came to purchase prisoners captured by the Iroquois, including Marguerite André and Deerfield captive Sarah Allen, remains a mystery. While he may have “redeemed” these captives, it's likely that his actions were transactional in nature, driven by the practical need for labor. Jean often hired servants and apprentices for various jobs, which might explain his interest in obtaining captives.

Jean was also the brother-in-law of François Vinet dit Larente. [Though he signed his name as Quenet, Jean is sometimes referred to as Guenet.]

On March 1, 1701, Marguerite once again enlisted the services of notary Adhémar, this time for a much happier occasion. On that date, Adhémar drew up her marriage contract to François Vinet dit Larente. Marguerite was still residing with Jean Quenet, who also acted as one of her witnesses. The contract reveals that "four years ago, he [Quenet] removed her from the Iroquois, then our enemies, where she had been a prisoner since 1689 and the Lachine fire." The marriage agreement followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The prefix dower was set at 400 livres, and the preciput at 200 livres. Neither the bride nor the groom could sign their names.

The couple was married on the same day in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montréal. Both François and Marguerite were listed as residents of Montréal, though their origins were noted as Lachine. After their wedding, they settled in Lachine.

François and Marguerite had two children:

1. Marguerite (1701-1745)

2. François (1703-1760)

Tragically, François Vinet dit Larente died at the young age of 22 on January 18, 1703, “in his bed due to illness.” He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Lachine. François may have been a victim of the smallpox epidemic that ravaged the colony, killing between 1,000 to 1,200 people in 1702 and 1703—approximately 8% of the Canadian population at the time.

On June 25, 1704, notary Adhémar drew up a marriage record between Marguerite and Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois, the son of René Dubois dit Brisebois and Anne Julienne Dumont. This contract also followed the standards of the Coutume de Paris. The prefix dower was set at 600 livres, and the preciput at 400 livres. Jean Quenet once again served as a witness for Marguerite.

Marguerite and Jean Baptiste were married on the same day in the Saints-Anges parish of Lachine. The groom was 28 years old, and the bride was around the same age. Neither was able to sign their name on the marriage record.

1704 marriage of Marguerite André and Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois (Généalogie Québec)

Marguerite and Jean Baptiste first settled in Lachine and had seven children:

Suzanne (1705-1775)

Louis (1707-1789)

Jacques (1709-1775)

Ambroise (1711-1798)

Marie Dorothée (1714-1794)

Toussaint (1717-1791)

Marie Anne Clémence (1720-1758)

Sometime around 1712, the family moved about ten kilometres west to Pointe-Claire.

Extract of the 1740 donation deed (FamilySearch)

On January 13, 1740, Marguerite and Jean Baptiste transferred all their possessions to their children, including Marguerite’s children from her first marriage. The notarial document states: “Wishing to rid themselves of worldly things and to think only of their own salvation, they have voluntarily given up and abandoned and forsaken everything from now on and for evermore.” The donation included a plot of land in Pointe-Claire, measuring six arpents of frontage along the St. Lawrence River by 20 arpents deep, with all the buildings on it, including a house, a barn, and a stable. However, the couple retained the right to live in the house and use the garden as they wished. The rent on the land was set at half a minot of wheat plus ten sols in cash for each 20 arpents of surface area.

In return, the children agreed to provide their parents with a dairy cow and a lifetime pension that included 40 minots of flour, 300 pounds of lard, 30 livres in cash, three shirts each, 30 cords of firewood, nine minots of peas to fatten up a pig, one pair of ox-leather shoes. Each child will also provide them with 12 bales of straw, six bales of hay, plus two pounds of lard annually. Additionally, every three years, the children promised to provide each parent with new clothing, hosiery, and shoes. The children from Marguerite’s first marriage were only required to contribute half of the pension obligations. Upon their parents' deaths, the children agreed to ensure that 20 masses would be said for the repose of their souls.

Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois died at the age of 71 on September 16, 1747. He was buried the following day in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire. His burial record noted that he held the rank of militia captain.

Marguerite André dite St-Michel died at around 75 years old and was buried on May 15, 1751, in the parish cemetery of Saint-Joachim in Pointe-Claire. The date of her death was not recorded in the burial entry.

Are you enjoying our articles and resources? Show your support by making a donation. Every contribution, regardless of its size, goes a long way in covering our website hosting expenses and enables us to create more content related to French-Canadian genealogy and history. Thank you! Merci!

Sources:

Bulletin des recherches historiques : bulletin d'archéologie, d'histoire, de biographie, de numismatique, etc. (Lévis, Pierre-Georges Roy, 1895-1968), page 406, 413, digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2657309 : accessed 30 Sep 2024).

“Registres paroissiaux et d'état civil : Courcelles-la-Forêt-1627 - 1679-1MI 1123 R2,” Archives de la Sarthe (https://archives.sarthe.fr/ark:13339/s005875e79d19780/58777479c2125.fiche=arko_fiche_6305cbbe7414a.moteur=arko_default_6319dbb9a1c43 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), baptism of Françoise Jacquine Nadreau, 20 Oct 1644, Courcelles-la-Forêt.

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8993-432P?i=380&cc=1321742&cat=299358 : accessed 2 Oct 2024), burial of several persons, 28 Oct 1694, Lachine > Saints-Anges-de-Lachine > Index 1676-1710, 1711, 1717-1859 Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1676-1778 > images 381-382 of 862; citing original data: Archives nationales du Québec, Montréal.

"Le LAFRANCE (Baptêmes, mariages et sépultures)," database and digital images, Généalogie Québec (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/47225 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), marriage of Michel Louvard and Francoise Jacqueline Nadereau, 23 Sep 1658, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal) ; citing original data : Institut généalogique Drouin and PRDH.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/48785 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), burial of Michel Louvard Desjardins, 24 Jun 1662, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal) ; citing original data : Institut généalogique Drouin and PRDH.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/47262 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), marriage of Michel Andre Stmichel and Francoise Nadreau, 18 Jun 1663, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/48830 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), burial of Marie Gertrude Andre, 20 Sep 1665, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/47805 : accessed 7 Oct 20242024), marriage of Francois Vinet and Marguerite Andre, 1 Mar 1701, Montréal (Notre-Dame-de-Montréal).

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/14630 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), burial of Francois Vinet Larente, 19 Jan 1703, Montréal, Lachine (Sts-Anges), Grand Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_mariages/14350 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), marriage of Jean Baptiste Dubois Brisebois and Marguerite André, 25 Jun 1704, Montréal, Lachine (Sts-Anges), Grand Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/118420 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), burial of Jean Baptiste Brisebois, 17 Sep 1747, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), Grand Montréal, Québec, Canada.

Ibid. (https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/lafrance_deces/278095 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), burial of Marguerite St-Michel, 15 May 1751, Pointe-Claire (St-Joachim), Grand Montréal, Québec, Canada.

"Archives de notaires : Benigne Basset dit Deslauriers (1657-1699)," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C344-QSKN-Q?cat=3228244&i=281 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), marriage contract of Michel André dit St-Michel and Françoise Jacqueline Nadreau, 20 May 1663, images 282-285 of 840, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C344-QSL4-N?cat=3228244&i=377 : accessed 26 Sep 2024), sale by Michel André dit St-Michel to Mathieu Gervaus dit le Parisien, 18 May 1671, images 378-380 of 815.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C344-QSKF-V?cat=3228244&i=498 : accessed 26 Sep 2024), land exchange between Michel André dit St-Michel and Françoise Nondereau, and Jean Leroy and Marie Demer, 11 Jun 1673, images 499-502 of 798, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C344-QSGG-7?cat=3228244&i=666 : accessed 26 Sep 2024), sale of an ox by Jan Leduc to Michel André de St-Michel, 8 Oct 1673, images 665-667 of 798, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C344-QS52-R?cat=3228244&i=296 : accessed 26 Sep 2024), survey of land located on the tip of the island of Montreal, 10 Dec 1678, images 297-305 of 729, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Archives de notaires : Claude Maugue (1677-1696)," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CST7-GSF4-L?cat=427707&i=20 : accessed 26 Sep 2024), sale by Pierre Mallet and Marianne Hardy to Michel André, 27 Dec 1677, images 21-23 of 2531, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

"Archives de notaires : Antoine Adhémar (1668-1714)," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS5F-B91C-Y?cat=541271&i=2468 : accessed 2 Oct 2024), testament of Marguerite André, 14 Jul 1699, images 2469-2472 of 3037, citing original data : Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTH-5389-B?cat=541271&i=1944 : accessed 2 Oct 2024), marriage contract of François Vinet and Marguerite André, 1 Mar 1701, images 1945-1947 of 3037.

Ibid. (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-2SNP-9?cat=541271&i=2736 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), marriage contract of Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois and Marguerite André, 25 Jun 1704, images 2737-2739 of 3100.

"Archives de notaires : François Simonet (1737-1778)," digital images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSTC-5T7C?cat=529340&i=1990 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), donation by Jean Baptiste Dubois dit Brisebois and Marguerite André to their children, 13 Jan 1740, images 1991-1998 of 3200.

“Fonds Conseil souverain - Archives nationales à Québec," digital images, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/402503 : accessed 8 Oct 2024), "Sentence condamnant les nommés Alexandre Turpin, Jean Quenet, Pierre Doret, Gabriel Guersaut (Guersant) dit Montaure, Antoine Villedieu, Michel Robert dit Le Picard et Gabriel Bérard dit Lépine à 2000 livres d'amende chacun (1000 livres au Roi et 1000 livres à l'hôpital de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Québec) pour être contrevenus à l'ordonnance du Roi contre les coureurs de bois; le nommé Doret à la somme de 100 livres d'amende et à 15 jours de prison et confiscation des 6 paquets de Castor saisis au logis dudit Bérard," 16 Nov 1680, reference TP1,S28,P2414, ID 402503.

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 25 Sep 2024), entry for Michel St-André dit St-Michel, 1666, Montréal, page 127 (of the PDF document), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada, 1667," Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&new=-8585951843764033676 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), entry for Michel André, 1667, Montréal, page 179 (of the PDF document), Finding aid no. MSS0446, Item ID number: 2318857; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 25 Sep 2024), entry for Michel André, 14 Nov 1681, Montréal, page 174 (of the PDF document), Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

Université de Montréal, Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) online database, (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/1601 : accessed DATE), dictionary entry for Michel ANDRE STMICHEL and Francoise Jacqueline NADREAU, union #1601.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/5644 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Francois PHILIPPON MAISONNEUVE and Marie Gertrude ANDRE STMICHEL, union #5644.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/5855 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Jean MICHEL GASCON and Jeanne ANDRE STMICHEL, union #5855.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/6399 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Charles BELONCQUE FUGERE and Petronille ANDRE STMICHEL, union #6399.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com.res.banq.qc.ca/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/8795 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Francois VINET LARENTE and Marguerite ANDRE STMICHEL, union #8795.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com.res.banq.qc.ca/Membership/fr/PRDH/Famille/9422 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Jean Baptiste DUBOIS BRISEBOIS and Marguerite ANDRE STMICHEL, union #9422.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com.res.banq.qc.ca/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/295 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), dictionary entry for Louise Madeleine ANDRE STMICHEL, person #295.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/Individu/67150 : accessed 2 Oct 2024), dictionary entry for Andre RAPIN SCAYANIFS, person #67150.

Ibid. (https://www-prdh-igd-com/Membership/fr/PRDH/famille/8795 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), dictionary entry for Francois VINET LARENTE and Marguerite ANDRE STMICHEL, union 8795.

René Jetté and the PRDH, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec des origines à 1730 (Montréal, Gaëtan Morin Éditeur, 1983), page 15, entry for Philippe André.

Peter Gagné, Before the King’s Daughters: Les Filles à Marier, 1634-1662 (Orange Park, Florida : Quintin Publications, 2002), p. 235 ; citing : Auger, Grande Recrue, p. 83. Quoted from the Documents judiciaires of the Archives judiciaires de Montréal.

Édouard-Zotique Massicotte, Faits curieux de l'histoire de Montréal (Montréal : Librairie Beauchemin limitée, 1922), 23-25 ; digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2022212 : accessed 26 Sep 2024).

Robert-Lionel Séguin, La Vie libertine en Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle (Québec : Septentrion, 2017), 540 pages.

Désiré Girouard, Les anciennes côtes du lac Saint-Louis avec un tableau complet des anciens et nouveaux propriétaires (Montréal : Poirier, Bessette & cie, imprimeurs, 1892), 52, digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2022735 : accessed 27 Sep 2024), p. 7.

Désiré Girouard, Le Vieux Lachine et le massacre du 5 août 1689 : conférence donnée devant la paroisse de Lachine, le 6 août 1889 (Montréal : Cie d'imprimerie et de lithographie Gebhardt-Berthiaume,1 889), digitized by Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2022736 : accessed 7 Oct 2024), p. 31-32.

Jean-François Nadeau, "Il y a 325 ans, le massacre de Lachine," Le Devoir (https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/415182/il-y-a-325-ans-le-massacre-de-lachine : accessed 2 Oct 2024), published 5 Aug 2014.

Hélène Lamarche, “Les victimes du massacre de Lachine (1689 -1691) : Désiré Girouard revu et corrigé," La Dépêche du fort Rolland, Société d’histoire de Lachine, Numéro spécial Lachine 1689, 25 Feb 2002 – 24 Apr 2003, digitized by genealogie.org (http://www.genealogie.org/club/shl/Site/Massacre_de_Lachine_files/Les%20victimes%20du%20massacre%20de%20Lachine%201689-1691.pdf : accessed 2 Oct 2024).

“The Lachine Massacre,” Canada: A People's History, CBC Learning (https://www.cbc.ca/history/EPCONTENTSE1EP3CH1PA4LE.html : accessed 27 Sep 2024).

“Le massacre de Lachine, un événement oublié à force d’être réévalué," podcast episode, Aujourd'hui l'histoire, Ohdio (https://ici.radio-canada.ca/ohdio/premiere/emissions/aujourd-hui-l-histoire/segments/entrevue/153356/massacre-lachine-1689-eric-bedard : accessed 7 Oct 2024).

Pierre Margry, Mémoires et documents pour servirà l'histoire des origines francaises des pays d'outre-mer : découvertes et établissements des Francais dans l'ouest et dans le sud de l'Amérique Septentrionale (1614-1754) (Paris : Maisonneuve et cie., 1879), 43-44, digitized by Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/mmoiresetdocum05marg/page/42/mode/2up : accessed 2 Oct 2024).